![]()

1 : First Encounters

When Korea, long known as the Hermit Kingdom, opened its doors to the world, its people faced a dizzying barrage of first encounters. Businessmen, missionaries, soldiers, and statesmen from all corners of the world brought new inventions, languages, weapons, and rules. That first generation, those who were adults between 1880 and 1910, are the ones against whom the explosive crash of opposing ideas hit with unexpected force. They should tell this story, but they are no longer alive. Their children speak for them.

KANG PYŎNGJU [KANG BYUNG JU] (m) b. 1910, bank manager, North P’yŏngan Province:

I want to tell you about my grandfather, Kang Chundal. He was born in 1850, during the reign of King Ch’ŏlChŏng, in our clan village to the east of Chŏngju city. Grandfather belonged to a long line of traditional village elders. He held strongly to that tradition and never ventured far from his village, but when the outside world shoved new ideas within his grasp, he was ready.

Grandfather’s adult life was a time when cultural earthquakes rocked our country. The modern world knocked, pounded, and battered its way into our consciousness. Now remember, our northern part of the country had been settled centuries earlier by free thinkers who had fled or been exiled from the royal court.1

These people did pretty much as they pleased, and most actually welcomed these modern innovations. My grandfather made four major changes.

First, Grandfather became a Christian. Around 1895, already forty-five years old, he set out one day from our village to the neighboring city of Chŏngju. His white robes and wide-brimmed hat blended in with all the others in the crowded city.

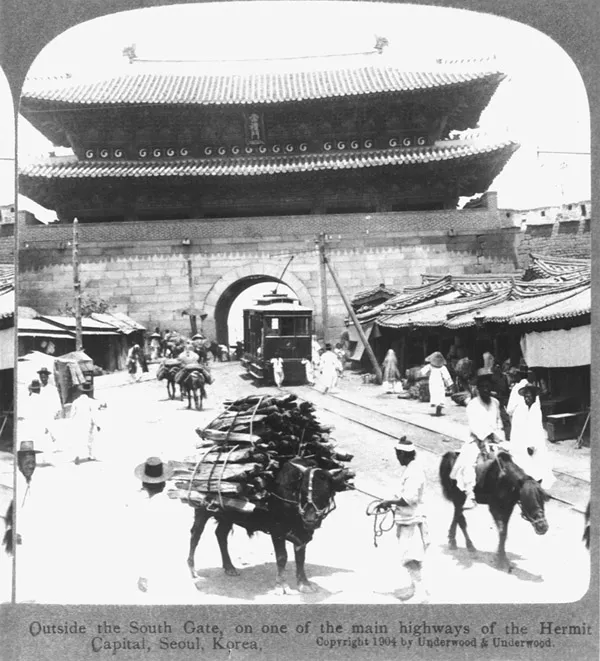

Outside Seoul’s GreatSouth Gate (Namdaemun) ,

showing one ofthe early trolley cars. 1904

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62–72551)

On this day a foreigner stood in the street talking about a new religion. The message intrigued him, and soon he became one of the first converts to Protestant Christianity. Can you imagine what it must have been like when he returned to his village? Since he was the patriarch, he just made everybody in our village change to Christianity, whether they liked it or not.

His next major change came in 1900, when he chose a name for his new daughter-in-law and added it to the hojŏk (local registry for citizens) which until then had listed women without their names, only “so-and-so’s daughter.” It happened like this. Grandfather’s son (my father) was 13 when he got married that year. His young wife had no personal name and that didn’t matter, because in Korean tradition we don’t call people by their personal names, anyway.

However, when these children married, it was just after the Kabo Reforms of 1894–95, which included a new law saying women should be listed by name in the family’s household register.2 Most families ignored this, but our grandfather recognized another tradition he was ready to break.

Of course, in order to register the daughter-in-law, she had to have a name. Grandfather picked two syllables—most Korean names have two syllables. He chose one from his son’s first name, Sŏhyŏng, and made up the other. Her name became Sŏyun.

Eight years later, he sent his son to school. A western-style school, Osan High School, had just opened in our area, teaching history, science, and mathematics instead of the Chinese classics.3 Yi Sŭnghun, a Korean, started this boys’ school, not the Japanese.

The school opened in 1907 and within a year Grandfather decided that his son should attend. Think of it. This school was brand new. There was no preparation for it. Any boy or man who qualified entered these first classes. So my father entered the school when he was twenty-one years old, eight years married, and a father himself.

Finally, in 1912 and sixty-two years old, Grandfather made his fourth and final break with tradition. He sent his only son away from the village to learn to be a doctor of western medicine, and so my father became one of the first to graduate from the Keijo Medical College. (In fact, just recently I received from Seoul a document commemorating his graduation.) When he finished his schooling, he returned to our village and opened a medical practice in nearby Napch’ŏn, about a twenty-minute walk away.

The story is that since Father had such good schooling, and had been married very young to a woman who had no schooling at all (the custom in those days), he was not happy living with her in the farm village. He told my mother to “just do what you want” with the property, and he went off to Manchuria to practice medicine and live his own life. After that, Mother ran the entire estate, and kept track of the tenant farmers.

Remember, the Manchurian border was very near to our village. I think Father returned to visit his family several times a year, because he had seven children born between 1906 and 1928. These parents educated all seven children through both high school and college—all of us, three boys and four girls. This is amazing because it was still a time when girls rarely even went to high school.

Here is a story my father told from his time in Manchuria. A Manchurian warlord had heard that he could live forever if he ate the liver ripped out of a living person. One day Father was summoned to the warlord’s headquarters.

“I hear that you are a western-style doctor. You can do surgery?”

“Yes, Your Honor.”

“Three soldiers have been captured and are about to be executed. Before I kill them, while they are alive, you must choose one and cut out his liver.” The warlord stared, waiting.

“No. I cannot do such a cruel thing,” Father answered.

“Then I will execute you, also.”

So Father did as he was told.

I remember one day when I was about five, so it must have been in 1915, Grandfather was putting a thatched roof on the pig pen behind the house and I was playing nearby. Suddenly, over the Sŏdang Hill, one of the hills surrounding our village, appeared Japanese military police in their shiny brown uniforms followed by their Korean aides.

In those days, Koreans weren’t called policemen, but rather assistants. The colonial government wanted help securing the country to its own advantage so it recruited Korean men who could speak Japanese. It gave these men black uniforms and had them walk alongside the brown uniforms of the military police.

About a dozen of these arrogant fellows descended upon us, surrounded Grandfather, bound him with rope, and started to take him away. They didn’t notice me. I hurried inside and told Mother. She ran out and pleaded with the police.

“What has my father-in-law done that you bind him and drag him away?”

She carried on, cried, pleaded, but they kicked her and took him away. We never knew the reason. He came back in a few days.

Here is a story that shows just how wealthy my Grandmother Kim’s family was, and how tight they were with their money. It also shows how our troubles came, not just from the Japanese, but from our own men as well. After the Japanese occupation, many Koreans used guerrilla tactics to fight the Japanese. They called themselves the Independence Army. To pay for their fighting, they went around extorting money from wealthy people. They did not bother us Kangs at all, but they earmarked the Kims. The Kims were warned to get money ready, because the guerrillas would be back for it. The father of the family was so reluctant to part with money that when the army returned he wouldn’t give them any, and right there, the soldiers killed him.

Yi Sangdo’s father, on the other hand, rejected everything western and became a proponent of the new religious movement called Tonghak, or “Eastern Learning,” which brought together elements from Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, proclaimed equality for the peasants, the betterment of village conditions, and reform of the corrupt government.

YI SANGDO, (m) b. 1910, truck driver, Kyŏnggi Province:

I want to tell about my father. He was a preacher of Ch’ŏndogyo, Tonghak. This “Eastern Learning,” very chauvinistic, rejected all western things as defiling Korean tradition.

Father did not get paid for preaching. My elder brothers supported him. The believers, instead of giving a cash offering, gave small units of rice depending upon how many members were in their family. This was sold and the money sent to Seoul to pay the expenses at the religion’s headquarters.

People came to our large house to make plans for rallies. I remember meetings in our house—secret meetings. Once I heard grownups talking about a rally where they would cry out “Mansei, Mansei” (May Korea live ten thousand years).

Father hated the Japanese coming, but to me, they weren’t al that bad. “Whenever we had a rainy season, our village flooded. Look what happened: Those Japanese came and built reservoirs, dams, and bridges. One of the taxes had to be paid in rocks. Each family had to go out two or three times a year and find a certain amount of small rocks. They used these to build roads.

I must say their organization impressed me. They planned things. They came with blueprints. They built things that worked. The bridge they built in our village lasted through all the rains and flooding. They also brought little things—sharp razor blades, matches that caught fire quickly, the record player—I know that those came from Europe, so eventually we would have gotten them. But the Japanese brought them first. I think probably it was good, in the long run.

The early Japanese policies were not kind to Korea. Japan stationed a large army in Korea, plus thousands of Japanese civil servants. The first governor, General Terauchi Masatake, put a Stranglehold on Korean political and economic development. He prohibited meetings, closed newspapers, and ordered burned over 200,000 books containing information such as Korean history, Korean geography, and free-thinking modern ideas. A tight network of spies and informers worked alongside the police, and by 1918, over 200,000 Koreans had been labeled rebellious, arrested, and tortured.4

People were arrested, often with no idea of what was charged against them, and the most innocent act could bring unexpected repercussions. One gentleman told how his father’s purchase of a cow brought the Japanese police. “‘Where did you get the money?’ they asked. You must have been spying.’ He was then ordered to report to the police station every single morning at nine o’clock.”

YI SŬNGBONG, (m) b. 1912, tailor, Kyŏnggi Province:

My uncle was a cavalry officer under the old Korean kingdom. When the Japanese took over, he had some problem because of his former military position. I was told not to talk about it. I think they didn’t want me to know.

YI OKHYŎN, (f) b. 1911, housewife, North P’yŏngan Province:

Grandfather on my mother’s side was an educated man, so knowledgeable in Chinese, I am told, that when the king of Korea sent a mission to China, my mother’s father accompanied the mission as interpreter.

This grandfather, in order to avoid the war between Japan and Russia in 1904, moved to Ko’ŭp, a small village near the Manchurian border by the Yalu River. He bought up lots of land and settled there. We became a prominent family in the community, so that my father’s elder brother, my first uncle, became myŏnjang, head of the township.

KIM WŎN’GŬK [KIM WON KEUK], (m) b. 1918, Tobacco Authority officer, North Hamgyŏng Province:

My father was President of the Young Businessmen’s Association in our area and one of the first modern Koreans to cut his hair short.

We owned one of the largest plots of land in the area, with about 20,000 p’yŏng [a p’yŏng is a unit of area about 6′ × 6′]. We had an orchard with 3,000 trees, and lots of potatoes, most of which were used to feed the pigs that we raised. We also raised rabbits and chickens. We fenced off part of the mountain behind the village and in that area we let loose about 500 chickens. The trees dropped leaves and seeds that made food fo...