1

INTRODUCTION

Structural Violence and Transnational Migration in the Gulf States

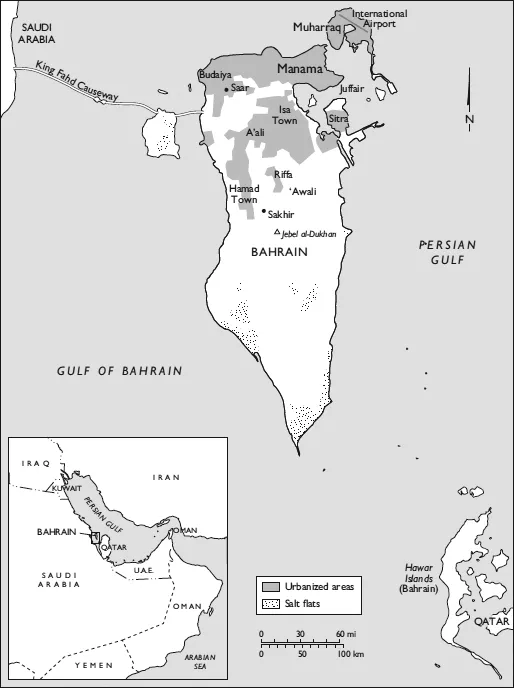

In the early months of 2006, newspaper headlines in the Kingdom of Bahrain reported that police, officials from the Indian embassy, and a collection of human rights activists, after receiving a tip from an undisclosed source, had converged on a scrap yard in the suburb of Hamad Town, a government-constructed quarter in the Manama suburbs where significant numbers of the citizenry’s lower middle class make their home. The owner of the garage and scrap yard, it seems, had sold a work visa to an Indian laborer by the name of Karunanidhi for BD1,200 (1,200 dinars), the equivalent of US$3,189. Although many of the details remain unclear, indications suggest that Karunanidhi then paid another individual to replace him at the work site, a move that angered the owner of the establishment and issuer of the work visa. The Bahraini owner grabbed Karunanidhi—in other words, moved him by force—and put him under an overturned bathtub in the scrap yard. He then parked his jeep over the bathtub, trapping Karunanidhi underneath, locked the vehicle, and departed for Manama, the central and singular urban center on the small island. In Manama, the scrap yard owner found his way to the flat that Karunanidhi rented with a large group of other Indian men and somehow kidnapped six of the Indian laborer’s roommates. Returning to the scrap yard with the men, he locked them in a large freezer, where they remained until the loose amalgamation of help—the aforementioned police force, officials, and activists—came to their rescue. All the men were freed, although their fate in the agencies and courts that govern the foreign population on the island remains in limbo. The scrap yard owner was briefly jailed and then released.

In the Gulf newspapers that carried this story, many of the articles and letters framed the case as atypical—a sponsor “gone bad”—or as the worst that might be faced by a member of the large transnational labor force on the island, while seeking a better life in the petroleum-rich nations of the Arabian Peninsula. In 2002 and 2003, however, I spent a year in Bahrain collecting ethnographic data that sought to explore the intricate matrix of relations between citizens and foreigners on the island. I spent countless hours in the labor camps, most of which are located on the distant periphery of the city, and in the decrepit urban flats, like the one described in Karunanidhi’s story, that now comprise much of the central city. The story I have just related—from February 2006—fits seamlessly into the tapestry woven by the many migration narratives I heard on those evenings in the labor camps and urban flats. These narratives, along with the newspaper clippings I have collected since departing the field, abound with accounts of stabbings, murders, rape, deportation, confinement, physical abuse, confidence games, extortion, suicides, suicides under suspicious circumstances, workplace injuries, debilitating illness, and more. Moreover, although there are certainly religious, gender, and class aspects to this violence, the most reliable pattern underpinning these events pits citizens against foreign laborers.

Sadly, reliable statistical data concerning the scope of this violence are not available. In the hallway outside my university office, however, I have a large bulletin board, perhaps four feet by six feet, on which I maintain a testament to the comprehensive violence committed against Indian laborers in Bahrain. The board, comprising a subset of the newspaper clippings I amassed from the local papers during my year in Bahrain, hints at the scope of the almost daily violence that plagues the Indian population of some 140,000 who make their home, however temporary, on the island. In light of this small edifice to the Indian experience in the Gulf, the case with which I began this volume is but one episode in the ongoing, commonplace experience of foreigners on the small island, and hence is in my mind far from anecdotal. Rather, the case of Karunanidhi and his time under a junkyard bathtub is symptomatic of the structural violence endemic to the system by which the large transnational labor force that currently works in the Gulf is managed and controlled in Bahrain and all the Gulf states.

Unpacking and applying the concept of structural violence is one of the principal tasks of this book. To be clear from the outset, however, in lodging the experiences of the men and women I encountered in the larger rubric of structural violence, I do not intend to imply that we should ignore the agency exerted in the scenario I’ve just described, or in the scenarios that litter this book: we ought not ignore the basic fact that these scenarios are composed of humans choosing to abuse, exploit, maim, and dominate other humans. Rather, I seek to couple that basic fact with an analysis of the structural forces that cause, permit, encourage, or are in some other way involved in the production of violence between citizen and foreigner in Bahrain. In the final accounting, the episodic violence levied against foreigners in Bahrain becomes one facet of the more comprehensive structural forces that govern foreign labor in the Gulf states.

Figure 1.1. Map of Bahrain.

The central mission of the anthropologist remains explication, and typically the explication of lives distant and different from those of the intended reader. The conceptual framework of structural violence, which I explore in detail, provides an analytic foundation from which I work outward in scope and, to some degree, backward in time. From that foundation I peer at the decisions and contexts that brought the men and women I came to know from India to the Gulf, at their experiences upon arrival in Bahrain, and at the strategies they deploy against the difficulties they face while abroad. I also examine the contours of the Bahraini state itself, the ongoing articulation of a particular idea of modernity in the Gulf, and the intricacies of the concept of citizenship as they have evolved in dialectic with the extraordinary flow of foreign labor to the island.

Perhaps the greatest danger with the thesis this book presents rests in its potential to fall in lockstep with the Orientalist punditry recently resurgent in Western public discourse. I am particularly concerned with potential misreadings of the theses presented here that suggest that the source of the structural violence I describe somehow inheres in the culture or character of the peoples of the Gulf. Instead, the political economic framework at the core of my analysis should make clear that although the structural violence I describe draws on the particular history and cultural framework of the Bahraini people, its ultimate source has more to do with the extension and expansion of a global labor market and neoliberal ideology to the Gulf states than with any particular qualities of Bahraini culture. The fact that structural violence seems to accompany the increasing proliferation of transnational movement should be a point familiar to scholars whose work concerns the United States’ southern border, or African migration to Europe, or the countless other movements that have come to typify the contemporary historical juncture.

Ethnography and Structural Violence

For much of its early history, the discipline of anthropology was principally concerned with the forces and social components that constructed and replicated harmonious and stable societies. For Émile Durkheim and other functionalists, the organic analogy provided the foundation for their understanding of society: particular aspects of society—religion, an educational system, family and kinship, and so forth—were viewed as analogous to organs of the body, working together to produce a static equilibrium. In functionalist analysis, each of those social components plays some particular role in the survival and replication of the social whole. Deviance, violence, and other nefarious social forces were seen as abnormal, as a breakdown in the status quo, or as circumstances produced by an unusual set of external conditions.

In that light, the shift of the anthropological lens to power and violence can be seen as the culmination of a disciplinary corrective, one that moves away from idealistic portraits of harmonious social forms and directly addresses the dilemmas, social problems, and rampant poverty observable in the contemporary world. The exertion of power and the resulting violence that oftentimes accompanies it are no longer portrayed as strange or extraordinary circumstances but rather have become essential focal points in the analytic mission of contemporary anthropology. In addition to positing ruptures and social dissonance as a seemingly constant facet of human life, this corrective also challenged the underlying functionalist premise that societies were best comprehended as unconnected, discrete social wholes. Eric Wolf, Sidney Mintz, and a strong cohort of other anthropologists working in the second half of the twentieth century built upon a political economic framework in arguing that change and interaction, often on a global scale, were central facets of the historical period. These approaches remain key in understanding the transnational context of the contemporary era.

Many of these ideas were distilled by William Roseberry, a scholar who envisioned an anthropology that manifests “an intellectual commitment to the understanding, analysis, and explication of the relations and structures of power in, through, and against which ordinary people live their lives…. The routes toward an analysis of power can be various, from the political-economic analysis of the development of capitalism in a specific place, to the symbolic analysis of the exercise of power in a colonial state, to a life history of a person who experiences power from a particular position, in a particular way” (Roseberry 1996, 6).

The concept of structural violence provides one of many possible pathways to these goals. First purveyed by Johan Galtung (1969) as a way of connecting the poverty and inequality experienced by legions in the world to the intricate mechanics of the global political economy, the concept’s key components remain in place today. That extreme poverty and social marginalization characterize the lives of those peoples traditionally found in the anthropological lens has been observed by Farmer (2004, 307) but was perhaps most eloquently stated by Bourgois when he said that, “with few exceptions, the traditional, noble, ‘exotic’ subjects of anthropology have today emerged as the most malnourished, politically repressed, economically exploited humans on earth” (1991, 113). As a conceptual framework, structural violence provides a tool for connecting the everyday violence of those conditions with their systematic and broad sources.

As Farmer states, the concept of structural violence is configured to examine the social machinery of oppression (2004, 307). Within this larger framework there are slight variations in focus. For Philippe Bourgois and Paul Farmer, the focus remains squarely upon the political economic relations that render these structural, violent results. For Nancy Scheper-Hughes, structural violence points to more discursive and ideological terrain—to the processes by which everyday violence is normalized and naturalized in public consciousness. She targets “the invisible social machinery of inequality that reproduce social relations of exclusion and marginalization via ideologies, stigmas, and dangerous discourses … attendant to race, class, sex, and other invidious distinctions” (Scheper-Hughes 2004, 13). Alternatively, for Daniel Goldstein (2004) the violent lynchings he observed in Cochabamba City, Bolivia, were best understood through their performative function as public spectacles through which community and collectivity were delineated. In spite of these differences, these and the many other texts concerned with theorizing violence are a testament to the diverse paths to the analysis of power sketched by William Roseberry. All share a concern for power, inequality, and the backdrop of a global, capitalist political economy that renders a particular terrain of suffering.

Discussions of structural violence often elide Eric Wolf’s contribution to the topic—a contribution that I find particularly clear. In his final book, Wolf described power in terms of four valences, or modalities, woven into social relations. The first is the power that individuals bring to their interactions with other individuals in the world. The second is the “power manifested in interactions and transactions among people and refers to the ability of an ego to impose its will in social action upon an alter” (Wolf 1999, 5). For Wolf, the third modality of power consists of the ability to manipulate and control the contexts and settings in which those interactions occur, a mode he refers to as organizational or tactical power. Working outward in scope, he concludes with a description of structural power, or “the power manifest in relationships that not only operates within settings and domains but also organizes and orchestrates the settings themselves” (5). It is this notion of power, and particularly the notion of a set of forces orchestrating relations between foreigners and citizens, that guides my analysis in this book.

Wolf’s valenced conception of power provides the impetus for the theoretical revision I use in this book. For the progenitors of the concept, structural violence is typically distinguishable from other forms of violence, and particularly from the everyday, interpersonal violence that purportedly inheres more closely to the agency of those who deliver that violence. This rendition of structural violence is entirely useful: it is adept at connecting broad structural forces and political economic conditions to the suffering that we increasingly encounter in the regions and places where many anthropologists work. The same rendition of structural violence helps delineate the forces that push many of the men and women described in this book out of India and across the Arabian Sea, for their journey and the suffering they often endure while abroad are, certainly, part of a coping strategy connected to forces well beyond the ambit of their everyday lives. But Wolf’s notion of the orchestration at work in this process also provides an opportunity to connect the everyday, interpersonal violence and suffering many of the foreign workers in the Gulf states endure with the structural arrangements that so intricately construct, limit, and govern their existence in the Gulf. This marriage of Wolf’s notion of structural power with structural violence opens another path to examine “how power operates not only on the global scale but in the daily lives of the people with whom anthropologists work” (Green 2004, 319).

Social Research in the Gulf States

My interest in transnational migration first bloomed during a two-week stay in Jeddah, the cosmopolitan hub of Saudi Arabia perched on the shores of the Red Sea. There I was the junior member of a team of ethnographers commissioned to examine the impact of the 1991–92 Iraqi conflict on the Bedouin nomads of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. When the team arrived in Jeddah, we discovered that the various bureaucracies overseeing our work had yet to procure the money and documents necessary for our trip to the remote deserts to the east. The government offices seemed to close around one in the afternoon—or at least the individuals we needed to speak with were absent after that—so in the afternoons I wandered the center of the city, strolling through the winding streets and alleys of the central souk, or marketplace, and basked in the air-conditioned environs of the modern shopping malls that had arisen around the aging center of the city.

In those first days in the Middle East, I was astounded by how infrequently I encountered Saudis in Saudi Arabia. In the stores of the souk I met Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi merchants; in the hotel the Filipino concierges greeted me in English. One evening, near the city center and in search of an Internet connection, I found my way to a large bowling alley and, just before the doors were locked for the evening prayer, I dodged inside. There I found myself amid the playoffs of a Filipino bowling league. By the time we left Jeddah for the deserts to the east, I had met men from a dozen different nations, all there to make a better life for themselves and their families back home. Yet my first look into the world of Gulf migration hardly ended at the city limits. In the weeks that followed, we spent our days on the dirt tracks that lace all points of the eastern deserts together, building an ethnographic foundation for a project I later described in two articles (Gardner 2004; Gardner and Finan 2004). Here we found migrant laborers alone on the sands of the desert, enmeshed in the livelihood systems of the Bedouin nomads, tending herds of sheep, goats, or camels for Bedouin families now relocated to nearby towns.

It was a small set of memorable experiences—speaking with two Sudanese men alone at a gas station waypoint in the middle of the great eastern deserts of Arabia, and then again with a particular pair of Indian shopkeepers of central Jeddah—that first spurred my interest in this flow of transnational labor. In its original form, the research proposal I configured to the Fulbright Program proposed a project in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. After two or three months of work on the proposal, I began communicating with my professional contacts in the kingdom, and they rapidly noted the naiveté of the document I had constructed: they informed me that the Saudi government would never allow this research to be conducted. Under the guidance of my advisers I reworked the proposal for Oman. Meanwhile, on the heels of two months of intensive language training in the United Arab Emirates, I prepared a second proposal to the Wenner-Gren Foundation to conduct research in Dubai, the cosmopolitan and transnational apex of the contemporary Gulf (and a cit...