CHAPTER 1

Social Discord

Disputes, Vendettas, and Political Clients

What befell Christiaen van der Naet on January 12, 1489, as he sat outside a tavern in his small Flemish town of Deinze, eating and drinking with friends, was more akin to a satire-laced tale from the Burgundian Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles than a trigger to a killing. But it ended with a man dead and van der Naet in a panic, seeking shelter from his enemies by fleeing the county of Flanders and preparing a request for a ducal pardon to evade homicide charges, the confiscation of his goods, perpetual banishment, and perhaps even execution.

Van der Naet was an ordinary citizen of Deinze, a town recently devastated by warfare. With fewer than a thousand inhabitants, the little city lived in the shadow of Ghent, eighteen kilometers to its northwest. Although self-governing, with its own aldermen and jurisdiction, the city had the misfortune to be on a main road that led friends and adversaries to its powerful, often troublesome urban neighbor, and for that it paid a high price. Over the course of the late Middle Ages, Deinze had been a punching bag for larger forces in conflict with Ghent and its allies, repeatedly damaged and pillaged, sometimes by Ghent, as in 1328 and 1452, and sometimes by the dukes of Burgundy and their armies in their campaigns against Ghent and other rebellious cities, as in 1382. In 1488, just a year before the incident discussed here, German mercenaries in the service of Archduke Maximilian of Austria burned Deinze almost completely down in their military campaign against rebellious Flemish cities.1 The city suffered grievously from these continual scourges, its citizens seeming to live fear of the next wave of violence. In 1436, for example, a particularly difficult year, Deinze’s aldermen conducted a house-by-house survey to ensure that its inhabitants had the bare essentials to survive a cold winter.2 In 1489, the same year that Christiaen van der Naet ran afoul of the law, Deinze’s aldermen paid for two pitchers of wine for the celebrations of the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28, to “cheer up the people from the troubles they found themselves in”—a reference to the city’s destruction the year before.3

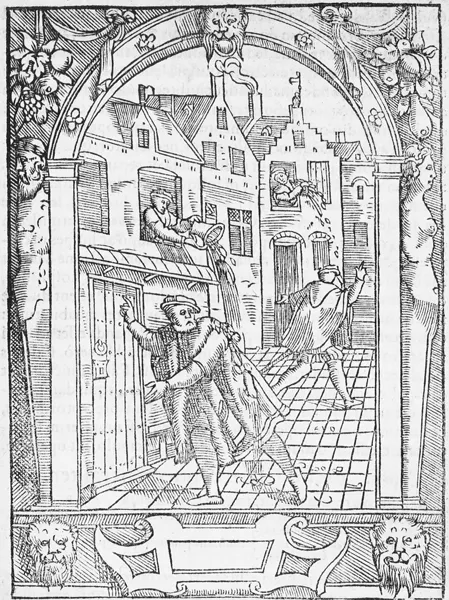

The misery inflicted by war and Deinze’s woeful state formed the backdrop to Christiaen van der Naet’s troubles. His pardon letter makes explicit reference to these challenges, describing how he and other families took up residence in the Saint George hostel because their houses had been burned down in “this war”—an overt reference to the intractable conflict between Archduke Maximilian and the rebels of Ghent (letter no. 1).4 While eating with several other neighbors also forced to lodge there, van der Naet had a chamber pot of urine and feces emptied on his head from a window above. It soaked him from head to foot, but more consequentially, it humiliated him before his friends, who, as van der Naet admitted, mocked him. These men were certainly drinking with their meal, and the sight of the contents of an upended chamber pot covering their friend provoked ribbing and guffaws. Van der Naet was furious, both embarrassed and dishonored in a social environment in which citizens were suffering already from the loss of home and income.

It is no surprise then that van der Naet went after the person who had exposed him to mockery by the careless emptying of a chamber pot. The culprit turned out to be the daughter of a fellow lodger in the Saint George hostel named Rogier de Marscalc. Neither her name nor her age is given by van der Naet, probably a sign that he wanted to downplay his retaliation against a young child or teenager. Van der Naet admits hitting the girl twice with the backside of a small axe as punishment, though he adds two qualifying points: first, that he regretted his actions, and second, that de Marscalc had afterwards accepted his personal apology. The father reassured van der Naet that his daughter merited her punishment, so much so that he had also struck her himself, especially because she had a habit of dumping chamber pots out of the window.

Throwing a chamber pot of urine out of a window of the Saint George hostel in Deinze. Etching from the treatise by Joost de Damhoudere, Praxis rerum criminalium (Antwerp, 1554), p. 499. Copy in the Library of Ghent University, Jur. 011275/1. Courtesy of the University of Ghent.

At play, but never discussed in the pardon request, was a man’s right to discipline individuals under his authority as head of a household. An ordinance of 1320–1340 from the city of Aardenburg in Flanders permits “that a husband may beat his wife, since the wife is part of his household effects.”5 When van der Naet struck de Marscalc’s daughter he could not claim this right, because she was the daughter of another man, and he ran the risk that de Marscalc might interpret his actions as a violation of his paternal authority. That is why van der Naet apologized: “He bid Rogier forgive him and not consider him poorly because he, the supplicant, had hit his daughter since everything had been done in jest.”

In van der Naet’s recounting of the incident, trouble broke out even though he had made amends to Rogier de Marscalc. His pardon letter recounts how he went to sleep that night in the church instead of the hostel where he lodged, fearing an attack by some enemies. It is not clear just who these enemies were or why they were a threat. Perhaps “enemies” referred to the extended Marscalc family, but perhaps the word recalled another set of adversaries, like the soldiers who were still in Deinze in 1489. Whatever the case, the very next day things came to a head. It was January 13, and van der Naet describes a day of piety—he was going to church to attend the evening service of vespers—and errands, including visiting a home that he had previously owned. On the way to church, Rogier de Marscalc confronted him as the two passed in the street. De Marscalc was visibly angry and armed with a pike in his hand; he excoriated van der Naet for attacking his daughter. Van der Naet attempted to diffuse de Marscalc’s agitation, asking why he was now mad after his supposed display of conciliation the day before. But de Marscalc lunged ahead at van der Naet, who struck back in self-defense. In the heat of anger—the pardon letter invokes the humoral theory of chaude colle to justify the sudden spike in emotion—Christiaen van der Naet stabbed Rogier de Marscalc with a dagger, cutting his left arm and piercing his chest. Afterwards, as if nothing had happened, van der Naet left the scene to attend vespers. In the days that followed, de Marscalc continued to hound him, even though, according to van der Naet, he was wounded—thereby proving himself a man whose drive for vengeance outweighed reasonable attention to his medical needs. Although he finally consulted a local surgeon at the urging of his friends, de Marscalc died eight days later. Christiaen van der Naet had no choice but to flee Deinze and Flanders, hounded by his victim’s “friends and relatives” who sought his arrest. Fearing his seizure by the bailiff, he prepared a formal plea for pardon, hoping to be excused for the murder of his neighbor. In June 1489, five months after the events, the archduke awarded van der Naet the remission, pending, as was customary, the verification and ratification of its narrative of events, and the payment of an unspecified sum for legal fees and a civil penalty.

Dispute Resolutions and Ducal Pardons

Public violence among private individuals was among the most disruptive of social problems facing legal and political authorities of territorial and civic jurisdictions in the late Middle Ages. The frequency of civil disputes, of vendettas, and of stories of private vengeance in our pardon letters shows just how often a killing involved more than just a perpetrator and a victim, and just how often, too, the individual petitioner was involved in a broader social conflict.6 The ducal pardon to prevent or end vendettas was a fifteenth-century development in the Burgundian Netherlands, part of a broader effort found elsewhere in Europe to use sovereign authority to crack down on feuds (conflicts between groups) and vendettas (conflicts between individuals)—the tenacious medieval practice, enshrined in customary law, that private vengeance was an appropriate response to a violent attack,7 and that adversaries’ families and male associates were fair targets.8 In England blood feuds were still a legally recognized practice in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but ceased by the reign of Edward I (1272–1307). In Scotland and Wales, however, blood feuds survived until the early sixteenth century.9 Paul Hyams claims that after 1200 English kings, like most late medieval rulers, asserted their legal power to resolve disputes but failed nevertheless to dislodge the traditional means of doing so through compromises, settlements, and arbitration.10

What was a popular sport of violence among aristocratic families widened out by the high Middle Ages among the urban middling sorts, as cities, especially in Italy and in the Low Countries, grew wealthier and more populated, and as families became enmeshed in conflicts and social and political factions. Most historians until recently have asserted that judges and city magistrates in medieval Italy explicitly tolerated vendettas and their private resolution through compensation. Trevor Dean, however, has proven, at least for the city-state of Bologna, that this wasn’t necessarily true. Revenge was treated in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italy as an ordinary crime. Pacification was no longer, as in earlier days, a private system of dispute resolution but instead was settled as a formal addition to the judicial sentence and ban. A convicted offender could no longer lift his ban if he did not comply with the court’s procedure of reconciliation between assailant and victim.11

Like northern Italy, the Low Countries were among the urbanized zones where vendettas and private vengeance were enacted, and there developed in these territories a multitiered system of tackling such violence. During the Middle Ages, the dukes and counts of the different territories at various times began to exercise the right to intervene to stop feuding. In Flanders, such interventions started as early as the twelfth century while in Holland and Zeeland, princely intervention to offset private vengeance began in earnest only in the late fourteenth century.12 In the legal realm, formal systems of resolution developed through both the office of the bailiff and the city aldermen, a subgroup of whom met separately in session as paysierders (peacemakers) to adjudicate disputes. Violent offenders in a feud could be summoned or arrested either by the bailiff in his capacity as ducal law officer or by the paysierders in their role as local aldermen. But an offender could also initiate a resolution. When an offender “composed” with a bailiff, he or she paid money to forestall further legal action and end a case. The two quarreling parties could also choose to approach either the bailiff or the paysierders together, offering compensation for the victim and the payment of a financial penalty to the legal authority.13 If the bailiff organized a settlement, it was referred to as a composition (compositio). If the paysierders settled matters, the procedure was called a zoen (reconciliation), and was recorded in the so-called zoenboeken (reconciliation books).

Only when the traditional means of reconciliation or composition failed to yield peace and a deal between the fighting parties could not be brokered did the case come before an urban or a ducal court. The parties in dispute had the right to take their grievance before a full session of the city aldermen themselves. Or the public authorities could summon the disputants to appear before the local court, or before the comital or ducal court, such as the Council of Flanders in Ghent.14 Cases that came to court were by far the minority. In Ghent, only 10 percent of all conflicts became criminal cases before the aldermen’s court in the second half of the fifteenth century; the paysierders settled a whopping 90 percent.

The paysierders proved popular because they were fellow townsmen of the offending parties with the same cultural orientation and urban sensibility, men who would often know the two parties better than any outsider. During the second half of the fourteenth century in Ghent, for example, the paysierders handled an average of 325 cases a year; in the zoenboeken of Leiden in Holland between 1370 and 1390, 722 sentences are recorded involving either deaths or serious injuries.15 The settlements of feuds and vendettas also kept bailiffs busy, not just with cases of violent death, but with other capital offenses such as rape, abduction, and robbery. In the year 1370 alone, the sovereign bailiff of Flanders handled seventy-six settlements, fifty-two of which were linked to either banishments or capital offenses.16

If the disputants could not reach an agreement, or if a peace agreement had been broken, the ducal pardon letter became a cherished third option. That men resorted to pardons for vendettas suggest, however, that these other legal avenues either worked imperfectly or were supplemented, perhaps even superseded, by this newer option to appeal for princely clemency.17 It was a ducal pardon letter that resolved the conflict between Christiaen van der Naet and the relatives of Rogier de Marscalc, ending the dispute—at least in a legal sense. Many others caught in the crosshairs of feuds would also resort to ducal pardons to settle violent, ongoing conflicts between family members and their kinfolk and others or to blunt them before they intensified. The pardon letter did not dislodge the well-oiled system of composition and reconciliation, but it did add, as in Bologna, another legal venue, sometimes short-circuiting the more traditional route and sometimes resolving problems when efforts at peace broke down with either the bailiff or the paysierders. More importantly, it affirmed the duke as the ultimate arbitrator of justice, and as the final and best adjudicator of violence when local and regional legal venues were rejected or failed—burnishing his image as the forgiving father and the restorer of social peace. Because the ducal pardon still required compensation to be paid out to the victim’s kin, it replicated the compensatory damages the bailiff and paysierders traditionally required. Of no small importance, a pardon additionally required a fee to be paid to the ducal treasurer, thus enriching the prince’s revenues.18 Frédéric Lalière observed that the pardon system was a clever blend of the traditional civic zoen and the bailiff’s compositio...