1

Understanding the Coercive Power of Mass Migrations

If aggression against another foreign country means that it strains its social structure, that it ruins its finances, that it has to give up its territory for sheltering refugees . . . what is the difference between that kind of aggression and the other type, the more classical type, when someone declares war, or something of that sort?

SAMAR SEN, India’s ambassador to the United Nations

Coercion is generally understood to refer to the practice of inducing or preventing changes in political behavior through the use of threats, intimidation, or some other form of pressure—most commonly, military force. This book focuses on a very particular nonmilitary method of applying coercive pressure—the use of migration and refugee crises as instruments of persuasion. Conventional wisdom suggests this kind of coercion is rare at best.1 Traditional international relations theory avers that it should rarely succeed. In fact, given the asymmetry in capabilities that tends to exist between would-be coercers and their generally more powerful targets, it should rarely even be attempted.2 However, in this book—which offers the first systematic examination of this unconventional policy tool—I demonstrate that not only is this kind of coercion attempted far more frequently than the accepted wisdom would suggest but that it also tends to succeed far more often than capabilities-based theories would predict.

I begin by outlining the logic behind the coercive use of purposefully created migration and refugee crises. Concomitantly, I also demonstrate that, contrary to conventional wisdom, these unnatural disasters are relatively common. I also outline how such cases are isolated, identified, and coded.3 In the second section, I describe the kind of actors who resort to the use of this unconventional weapon and why. I then highlight the diverse array of objectives sought by those who employ it. I also show that this kind of coercion has proven relatively successful, at least as compared to more traditional methods of persuasion, particularly against (generally more powerful) liberal democratic targets. I next propose an explanation for why democracies appear to have been most frequently (and most successfully) targeted. I also advance my broader theory about the nature of migration-driven coercion, including how, why, and under what conditions it can prove efficacious. I conclude with a discussion of case selection and the methodology employed in the case study chapters that follow.

Defining, Measuring, and Identifying Coercive Engineered Migration

I define coercive engineered migrations (or migration-driven coercion) as those cross-border population movements that are deliberately created or manipulated in order to induce political, military and/or economic concessions from a target state or states.4 The instruments employed to effect this kind of coercion are myriad and diverse. They run the gamut from compulsory to permissive, from the employment of hostile threats and the use of military force (as were used during the 1967–1970 Biafran and 1992–1995 Bosnian civil wars) through the offer of positive inducements and provision of financial incentives (as were offered to North Vietnamese by the United States in 1954–1955, following the First Indochina War) to the straightforward opening of normally sealed borders (as was done by President Erich Honecker of East Germany in the early 1980s).5

Coercive engineered migration is frequently, but not always, undertaken in the context of population outflows strategically generated for other reasons. In fact, it represents just one subset of a broader class of events that all rely on the creation and exploitation of such crises as means to political and military ends—a phenomenon I call strategic engineered migration. In addition to the coercive variant, these purposeful crises can be usefully divided by the objectives for which they are undertaken into three distinct categories: dispossessive, exportive, and militarized engineered migrations. Dispossessive engineered migrations are those in which the principal objective is the appropriation of the territory or property of another group or groups, or the elimination of said group(s) as a threat to the ethnopolitical or economic dominance of those engineering the (out-)migration; this includes what is commonly known as ethnic cleansing. Exportive engineered migrations are those migrations engineered either to fortify a domestic political position (by expelling political dissidents and other domestic adversaries) or to discomfit or destabilize foreign government(s). Finally, militarized engineered migrations are those conducted, usually during armed conflict, to gain military advantage against an adversary—via the disruption or destruction of an opponent’s command and control, logistics, or movement capabilities—or to enhance one’s own force structure, via the acquisition of additional personnel or resources.6

Coercive engineered migration is often embedded within mass migrations strategically engineered for dispossessive, exportive, or militarized reasons. It is likely, at least in part as a consequence of its embedded and often camouflaged nature, that its prevalence has also been generally underrecognized and its significance, underappreciated. Indeed, it is a phenomenon that for many observers has been hiding in plain sight. For instance, it is widely known that in 1972 Idi Amin expelled most Asians from Uganda in what has been commonly interpreted as a naked attempt at economic asset expropriation.7 Far less well understood, however, is the fact that approximately 50,000 of those expelled were British passport-holders, and that these expulsions happened at the same time that Amin was trying to convince the British to halt their drawdown of military assistance to his country. In short, Amin announced his intention to foist 50,000 refugees on the British, but did so with a convenient ninety-day grace period to give the British an opportunity to rescind their decision regarding aid.8 And Amin’s actions are far from unique.

Measuring Incidence

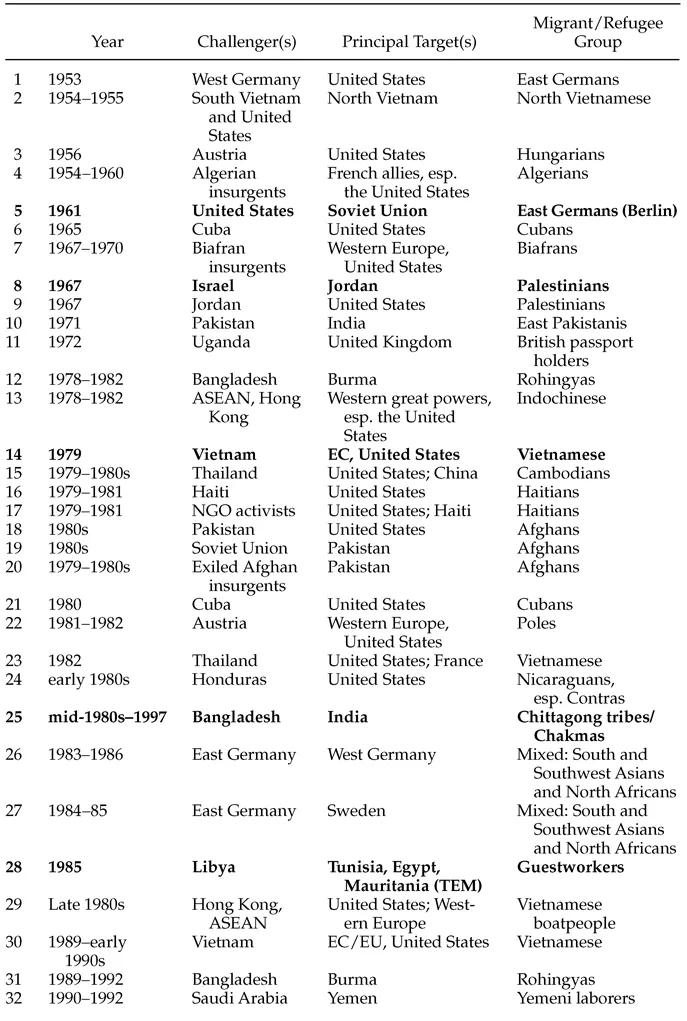

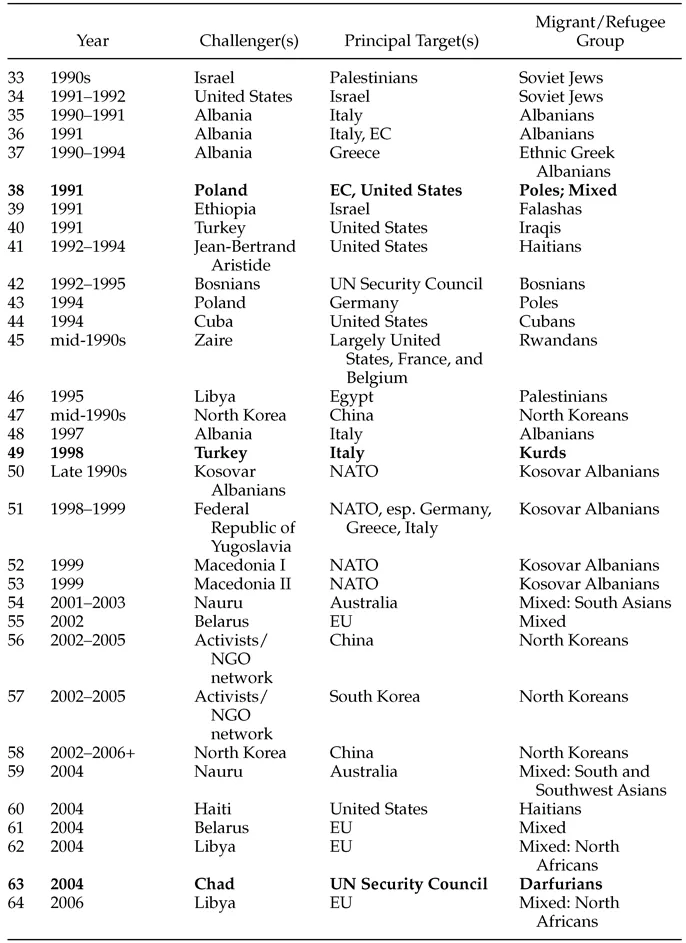

In fact, well over forty groups of displaced people have been used as pawns in at least fifty-six discrete attempts at coercive engineered migration since the advent of the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention alone. An additional eight cases are suggestive but inconclusive or “indeterminate” (see table 1.1). Employment of this kind of coercion predates the post–World War II era.9 However, in this book I focus on the post-1951 period because it was only after World War II—and particularly after ratification of the 1951 Refugee Convention—that international rules and norms regarding the protection of those fleeing violence and persecution were codified.10 It was likewise only then that migration and refugees “became a question of high politics” and that, for reasons discussed later in this chapter, the potential efficacy of this unconventional strategy really began to blossom.11

The numbers of migrants and refugees affected by these coercive attempts have been both large and small, ranging from several thousand (Polish asylum seekers in 1994—case 43 in table 1.1) to upward of 10 million (East Pakistanis in 1971—case 10). The displaced groups exploited have comprised both coercers’ co-nationals (e.g., Cubans who left the island in 1965, 1980, and 1994—cases 6, 21, and 44, respectively) and migrants and asylum seekers from the other side of the globe (e.g., Tamils used by East Germany against West Germany in the mid-1980s—case 26). As table 1.1 also indicates, there have been dozens of distinct challengers and at least as many discrete targets. However, for reasons I explore in detail later in this chapter, advanced liberal democracies appear to be particularly attractive targets; indeed, the United States has been the most popular target of all, with its Western European liberal democratic counterparts coming in a strong second.12

TABLE 1.1

Challengers, Targets, and Migrant/Refugee Groups, 1951–2006

Notes: Where discernable, the more powerful actor (challenger v. target) is shown in boldface. AP, agents provocateurs; ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations; EC, European Community; EU, European Union; G, generators; LT, long-term; NATO, North Atlantic Treaty Organization; NGO, nongovernmental organization; O, opportunists; ST, short-term.

But what shall we make of these numbers? To put the prevalence of coercive engineered migration in perspective, at a rate of at least 1.0 case per year (between 1951 and 2006), it is significantly less common than interstate territorial disputes (approximately 4.82 cases/year). But, at the same time, it appears to be markedly more prevalent than both intrastate wars (approximately 0.68 cases/year) and extended intermediate deterrence crises (approximately 0.58/year). At a minimum, this suggests that the conventional wisdom about the relative infrequency of coercive engineered migration (my operative null hypothesis) requires reconsideration. More ambitiously, it suggests that what we think we know about the size and nature of the policy toolbox ...