![]()

1

American Dream, American Work

Fantasies and Realities of Honduran Migrants

Chris Matthews: When I was in the Peace Corps I calculated it would take 350 years for the country I was serving in to catch up to where we [Americans] were in GNP in the sixties.

Brent Scowcroft: And that’s a horrible thought. That gets to one of the real problems in the world though, and that is the people where you were serving didn’t know much about the United States. Now they watch television every night. Even in the boondocks they watch television and they see you shopping on Fifth Avenue and so on and so forth and they think, “Why am I not shopping on Fifth Avenue?”

Transcript from MSNBC’s Hardball, television news program, Dec. 2, 2004

Many people are coming to this country for economic reasons. They’re coming here to work. If you can make fifty cents in the heart of Mexico, for example, or make five dollars here in America, $5.15, you’re going to come here if you’re worth your salt, if you want to put food on the table for your families. And that’s what’s happening.

Former President George W. Bush, presidential debate, Oct. 8, 2004

The quotations above contain two common explanations of contemporary migration to the United States, one “cultural” and the other “economic.” Former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft gives a cultural explanation of migration, arguing that increased knowledge of riches available in the United States, thanks to the global media, has altered individual and collective worldviews in “boondocks” around the world, leading to disillusionment and new aspirations shaped by consumerist desires. According to this form of reasoning, the worldwide spread of the Western media disrupts traditional concepts of status and value, leading to rising expectations for personal advancement, which Scowcroft calls “one of the real problems of the world.” Alexis de Tocqueville argued long ago (1856) that rising expectations are effectively the same as declining fortunes: They set the stage for widespread disillusionment and collective action as people’s lived realities fail to keep pace with their “expectations of modernity” (Ferguson 1999).1 I characterize this line of reasoning as a “cultural” explanation because it emphasizes how peoples’ decisions are shaped by subjective definitions of value, such as the meaning of “success” and “a good life,” that vary across cultures, classes, and generations.

The economic explanation of migration decisions, exemplified by President Bush’s comments in a presidential debate, views the decision to migrate as a common-sense response to economic conditions rather than one motivated by fantasies or dreams of upward mobility. Migrants are motivated by relatively high U.S. wage rates and the chance to support their families. (Note that Bush corrected himself to assure audiences that migrants were lured by the exact legal minimum wage of $5.15 per hour.) In this view, migrants weigh the benefits of U.S. wages against other factors and make a decision that “anyone worth their salt” would make. They are not lured by Fifth Avenue finery; they just want to “put food on the table,” implying that they send earnings home to support kin. These migrants are realists who are motivated by a conscious evaluation of risk and reward and not the pursuit of a television-fueled “American Dream.”

The cultural and economic explanations of migration have strong analogs in the social sciences, where the “culture versus economics” dichotomy provides a useful explanatory device to sort through a vast body of literature. Arjun Appadurai, one of the most influential anthropologists of globalization, has emphasized the importance of culture in shaping transnational migration, arguing that the flow of people and media images around the world has dramatically changed individual and collective subjectivity, allowing people to imagine “possible lives” and new aspirations that were once beyond the reach of their consciousness. Television, film, and the Internet have broadened horizons, changed consumer appetites, and, most important, changed people’s concepts of membership in a wider community—that is, their identity—creating a situation whereby “scripts can be formed of imagined lives…fantasies that could become the prolegomena for the desire for acquisition and movement” (1996, 36).

In their classic synthesis of late-twentieth-century migration to the United States, Alejandro Portes and Rubén Rumbaut (1996) make a similar point. They challenge the view “of migration as a consequence of foreign destitution and unemployment” (10), arguing that one of the key points of distinction between the “new” immigration of the late twentieth century and the “old” immigration of the late nineteenth century is that “contemporary immigration is a direct consequence of the dominant influence attained by the culture of the advanced West in every corner of the globe” (13). In general, contemporary migrants are not directly recruited to come to America to supply labor for industrial expansion as they were in the past. Instead, contemporary migrants tend to have experienced a gap between subjective expectations for success and lived experiences in their home countries. They seek “a car, a TV set, and domestic appliances of all sorts” (13) and wish to improve their standard of living to fit rising expectations. Therefore, people with some education and income (in the case of urbanites) or assets (in the case of small farmers) are far more likely to migrate than the poorest of the poor, who are not exposed to the lure of popular culture and do not have the economic resources to migrate.2

Within scholarship on contemporary Latin American migration to the United States, the distinction between “economic” and “political” migration is made to differentiate migrants who leave a particular country in search of economic opportunity versus those who leave to seek refuge from political persecution and war (García 2006). Economic explanations of migration tend to emphasize how macroeconomic changes produce flows of migrants from one place to another. For example, the demand for cheap agricultural labor in the rural United States, coupled with economic decline in rural Mexico, has produced an unprecedented flow of migrants from rural Mexico to the United States.3

Although there is no denying that macroeconomic forces produce migrant flows around the world, “structural” explanations, which emphasize the importance of economic systems over individual choices, can minimize the degree that human volition shapes behavior, viewing people as objects who are “pushed and pulled” (as one common model for explaining migration puts it) by macro-level forces. While I certainly do not wish to discredit structural explanations of migration (and, indeed, I will utilize structural approaches throughout this book), face-to-face ethnography offers a different kind of explanation of migration decisions. In this chapter, I investigate the subjective motivations of migrants in La Quebrada to provide a sense of the human complexity of migration decisions. Through a series of ethnographic profiles, I will present detailed examples of the motivations of a group of male migrants, emphasizing the variation in their life experiences. Even within a single community, there are many types of migrants—some leave in search of the consumerist American Dream (à la Brent Scowcroft), while others want to make a quick buck and return to Honduras (à la George Bush), and others migrate simply because it has become “the thing to do” for young men at a certain point in the life cycle. While virtually all migrants speak of being “forced” to go to the United States by economic pressures, they also recognize that they make a choice that other people in similar situations do not make.

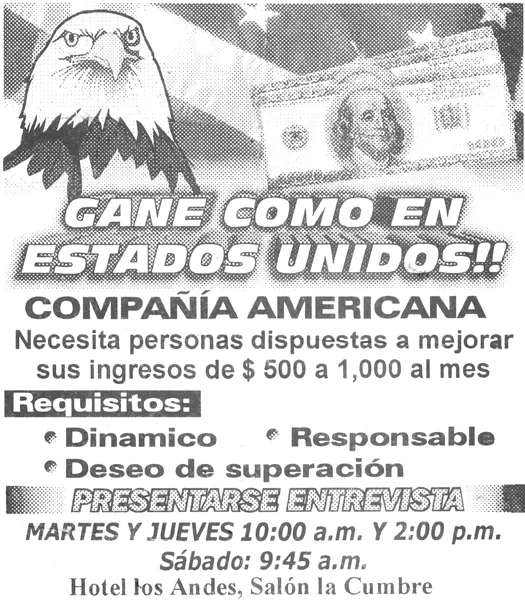

Wilmer Ulloa: A “Needy” Migrant

Near the beginning of my fieldwork, a young man named Wilmer told me that he had something to show me. It was a small paper flyer (figure 2) that someone handed to him as he got off the bus in a nearby town. The flyer was money-green, with words printed over a picture of a bald eagle, hundred dollar bills, and an American flag. The text read, “Gane como en Estados Unidos!!” (Earn like in the United States). Someone had handed the flyers to all the passengers on the bus arriving from the countryside. Below the headline it said, “American Company needs people willing to improve their income to $500 to $1,000 a month.” The flyer listed a woman’s name and telephone number, and the location of a meeting place where interviews would be held. The flyer stated that candidates should be “dynamic,” “responsible,” and have a “desire to succeed.” Wilmer suspected that the flyer was intended to recruit workers for a new maquila (sweatshop), but he wasn’t sure. He didn’t have time to go investigate. His pregnant wife was sick and he was taking her to the hospital at the moment he was handed the flyer.

Figure 2. “Earn Like in the United States!!” Flyer. 2003

I asked Wilmer if he believed what the flyer said: Could a company in need of workers pay between $500 and $1,000 a month? “Well,” he responded, “I have a cousin that works in a maquila making hospital scrubs for an American company. He makes about $500 a month, so it’s possible, but it’s very hard to get a job there. There’s no way they would need to hand out flyers to people like me.4 This thing can’t be true. It’s probably a Korean maquila. They pay badly and treat people even worse. If it really paid that much, people would be lining up to work there.”5 The flyer appeared to be a scam. Wilmer asked me if I believed the flyer’s offer, and I said that it appeared too good to be true. We both concluded that a company that paid such high wages (by Honduran standards) would not need to go hunting for employees at the bus terminal.

Wilmer and his wife had just had their first child, and they wanted to live in a home of their own. As it was, they lived in a tiny, dirt-floored, wattle-and-daub shack with Wilmer’s father, younger brother, older sister, and niece.6 Their home was crowded and had no electricity or running water, not because they were unavailable in the neighborhood, but because the family could not afford these services and did not consider them to be necessities. The family owned about five acres of land (milpa) three miles from their home, on which they grew maize, beans, squash, cucumbers, onions, tomatoes, and various herbs. They had a plot of coffee but could not fertilize it, and the plants were old and unproductive. The coffee plot provided a tiny income; as Wilmer said, “Hardly more than the cost of the sacks for the harvest.”

Wilmer’s only valuable material assets were a mule, a saddle, and a wristwatch that had been sent to him by a cousin who lived in New York City. Wilmer dropped out of school at fifteen, and could not read or write. Even by the standards of La Quebrada, he and his family lived a simple, self-sufficient lifestyle, yet they required cash for medicine, school supplies, shoes, clothes, cooking oil, and other necessities. To earn cash, Wilmer would slaughter hogs owned by others, and would walk around town taking orders for the fresh pork in exchange for a percentage of the sales. He was an exuberant, warm, and funny person—a charming salesman—and I used to enjoy going door to door with him to sell the portions of pierna (leg) and costilla (ribs). He thought that the presence of an American stranger would make people more willing to buy, and I would make up humorous little jingles or rhymes in Spanish to embarrass myself and make people laugh. He paid me in fresh chicharrones (fried pork skin or fried pork belly) to go with him, and I gladly accepted, not only because I liked the chicharrones but because this task enabled me to meet many people in town in an informal and light-hearted way. I had heard of many unique strategies that anthropologists used to establish rapport in the field, but door-to-door pork salesman was not on the list.

Wilmer felt that farming his family’s plot and working as a butcher-for-hire could not provide enough money for him to establish a home of his own. He had taken on small amounts of debt from kin to pay for his wife’s medical care during her pregnancy. In the past, he would have been able to earn some money by picking coffee during the harvest and by selling his own coffee crop, but due to the coffee crisis (see chapter 2), this type of work would not provide him with enough cash for basic expenses, let alone the repayment of debt. In 2002 and 2003, a hundred pounds of coffee cherries sold for about five dollars, and his plot provided about five hundred pounds. Twenty-five dollars does not last long, so Wilmer and the rest of the family picked coffee on other people’s farms. Coffee pickers were paid about two dollars per hundred pounds, which worked out to between four and eight dollars a day for a skilled picker. The harvest lasted only a few months, though, and not every day had plentiful pickings. The family earned most of the year’s income this way, but it was not nearly enough for Wilmer to move into his own home with his wife and child.

Wilmer told me that he was considering several options to improve his situation. The first would be to sell his mule and use the money to move to the city of San Pedro Sula to seek work in a meat-packing plant or maquila, using his cousin as a connection. The other option would be to go to the United States and try to find work there as an undocumented worker.7 He had heard that some people had found work in slaughterhouses or poultry-processing plants (Striffler 2002a) and reasoned that if he was going to do that sort of work, which he enjoyed, he might as well do it in the United States where he could get paid far more than he would in Honduras.

He considered the danger and expense of making the trip to the United States (about $100 dollars, by his optimistic estimate) and debated whether he should risk his life and separate from his family to seek work in the United States. He knew that he could not afford to pay a coyote (smuggler), so the chances of successful migration were slim. Most people who travel with a good coyote arrive in the United States on their first attempt, but it often takes solo migrants several attempts to cross the border. More important, his father was getting old and was increasingly unable to perform household chores. Wilmer’s teenage brother could pick up some of the slack if he was gone, but maintaining the milpa, which was three miles out of town, was too hard a task for one person.

He also openly worried that someone would try and seduce his young wife while he was gone, and he launched into a violent tirade, which was completely out of character, about what he would do to the man that did so, telling me how he would return from the States and bash the man’s head open with a brick. The mere thought of adultery sent him into a rage, offering a glimpse into some of the deeper fears and drives th...