![]()

1

THE HANDS ON YOUR PLATE

When you work in restaurants you think the industry is everything. It’s being outside, talking to people, serving people. You feel like you’re part of something good. People mostly go to eat out for good stuff—proposals, weddings, birthdays—not to fight. You’re part of someone’s proposal—you bring the ring in an ice cream cake, you watch her reaction. You feel like you’re part of their experience, their special moment, even if the people don’t care who you are—you’re just the server. Everywhere I go, I find restaurant workers are the same. They may move from restaurant to restaurant—maybe they don’t earn enough money, or they don’t like the way they’re being treated. But they always come back. They have a hospitality mentality in their DNA. All over the world, they have it in them.

—SERVER, MAN, 17 YEARS IN THE INDUSTRY, NEW YORK CITY

The events that forever changed me as a diner—and ultimately led to the writing of this book—happened shortly after 9/11. I had never given much thought to the inner workings of restaurants or the lives of restaurant workers, but a few weeks after the Twin Towers fell I received a call from a union leader representing workers from Windows on the World, the luxurious multilevel restaurant that had been at the top of the World Trade Center. Windows on the World had earned acclaim for its international cuisine and for its staff from almost every nation in the world. The caller wanted me to help build an organization to support the displaced Windows workers and some 13,000 other restaurant workers in New York City who had lost their jobs after the 9/11 tragedy. She knew I had experience organizing immigrant workers, including restaurant workers, on Long Island and that I’d helped start Women and Youth Supporting Each Other, a national organization serving young women of color. But I had never actually worked in a restaurant.

I was also young. I’d always loved eating out, but I had no idea that, in accepting the union leader’s offer and becoming at 27 the leader of a new restaurant workers’ organization, I’d spend the next 11 years of my life meeting low-wage restaurant workers—servers, bussers, runners, dishwashers, cooks, and others—who are struggling to support themselves and their families under the shockingly exploitative conditions that exist behind most restaurant kitchen doors.

It took me a while to understand what I was getting into—helping to improve the lives of men and women who belong to one of the largest private-sector workforces in the United States. And these workers perform important jobs—it’s the people behind the kitchen door who make a restaurant. We interact with them daily, but few Americans know that the majority of these workers suffer under discriminatory labor practices and earn poverty-level wages. In fact, although the restaurant industry employs more than 10 million people and continues to grow, even during recent economic crises, it includes 7 of the 11 lowest-paying occupations in America—an unenviable distinction.1 Plus, most employers in the industry refuse to offer paid sick days or health benefits.

So how do restaurant workers live on some of the lowest wages in America? And how do they feel about their work? What are their future prospects? And what impact does their mistreatment and poor compensation have on our experience as diners? These are questions I asked myself in the months after 9/11 as I met some 250 displaced workers from Windows on the World. They described to me in heartbreaking detail how 73 of their coworkers, mostly immigrants, had lost their lives on 9/11. Since the tragedy occurred early in the morning, the majority who died were low-wage kitchen workers who were preparing meals and setting tables for a large breakfast party that was scheduled for that morning. Many of them were incinerated. Several jumped to their death from the 106th and 107th floors of the building. Not a single one survived.

The owner of Windows attended a memorial service for the fallen workers and promised all of his former employees that he would hire them when he opened a new restaurant. However, when he opened a new restaurant in Times Square just a few months later, he refused to hire most of his former workers. He told the press that they were “not experienced enough” to work in his new restaurant.

The Windows workers were outraged. It would be almost impossible for them to find jobs comparable to what they had at Windows—with a union in that restaurant, they had higher wages than similar workers elsewhere, and benefits. Only 20 percent of restaurant jobs pay a livable wage, and women, people of color, and immigrants face significant barriers in obtaining those livable-wage jobs.2 As I listened to the workers’ stories, I felt their frustration and outrage—first, as men and women who wanted to be treated with dignity and respect in the workplace, and then as people of color who’d discovered that race affected their ability to hold a job and move up the ladder. I met a woman chef from Thailand who’d moved from restaurant to restaurant in the weeks after the tragedy; she couldn’t find a new position that would pay a living wage. I met an African American man who had been bartending for two decades; he couldn’t find a position that offered wages and benefits comparable to those he’d received at the Windows bar, “The Greatest Bar on Earth.” I also met several undocumented immigrants from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and eastern Europe, all of whom had found themselves at the mercy of unscrupulous employers who relied almost entirely on immigrant workers (approximately 40 percent of New York City restaurant workers are undocumented immigrants); these employers threatened to contact immigration authorities when their workers complained about exploitation and abuse on the job.

The union hired Fekkak Mamdouh, one of the headwaiters from Windows on the World, to work with me. Mamdouh, a Moroccan immigrant, had been a leader among his coworkers when the restaurant was still open. Medium-built, with cocoa skin, dark brown eyes, and black curly hair, he has a strong Moroccan accent and a mischievous sense of humor. He walks and moves fast and talks and laughs loudly. He’s the quintessential Gemini—the happiest guy to be around or, when his temper blows, the foulest in the world.

When I met Mamdouh, he had more than 17 years of experience working in restaurants. He’d started as a delivery person, worked his way up to server, and recently served as an elected union leader fighting on behalf of his fellow workers on a range of issues. Still, I was predisposed not to like him—people had told me he had an aggressive personality—but he completely disarmed me at our first meeting. He cracked jokes and made fun of my seriousness while also listening to me and respecting what I had to say. I found him sensitive, despite his bravado, always trying to make people feel welcome and comfortable. I also admired how he cared for his large extended family in the United States and Morocco—his wife and three children, his mother, and his eight brothers and sisters and their children.

Mamdouh and I cofounded the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC) in April 2002. We agreed that our mission would be to organize workers to improve wages and working conditions throughout the restaurant industry. Our first priority, however, was to advocate for the displaced workers from Windows on the World.

After one month on the job at ROC, Mamdouh and I called a meeting of all the surviving Windows workers, many of whom had applied to work at their former boss’s new restaurant. Since we didn’t have an office yet, we borrowed meeting space from the union. The workers packed the room. All of them wanted to do something. They felt desperate and humiliated, especially since their former boss had told the media that his former employees—many of whom had lost family and friends in the restaurant—were not qualified to work in his new place. After hours of heated discussion, the workers decided to hold a protest.

We protested loudly in front of the Windows owner’s new restaurant on its opening night. The workers showed up with their families in tow and picketed as celebrities entered the restaurant on a red carpet. A headline in the New York Times declared the next day, “Windows on the World Workers Say Their Boss Didn’t Do Enough.”

The coverage prompted the owner to ask Mamdouh and me to meet with him. A few days later we met the owner on the cold, dimly lit ground floor of his multistory restaurant. It was still early in the day, the restaurant not yet open. Before we could say much, the owner told us he was setting up a new banquet department for which he would agree to hire almost all of the workers who’d wanted to work in the restaurant. I couldn’t believe it. I thought it was a trick, or that perhaps it would be less than what the workers wanted, but Mamdouh assured me it was truly a victory. When we conferred in an empty banquet room of the restaurant, Mamdouh gave me a hug. “We did it!” he said.

The victory was covered in the New York Times. Best of all, the workers seemed happy. The next day I was interviewed on New York’s Channel 1. I explained that ROC was a new organization established to serve restaurant workers, and then the floodgates really opened: workers started calling us from all over the city, seeking our help. I realized that problems in the restaurant industry were pervasive, often insidious, affecting workers from every background.

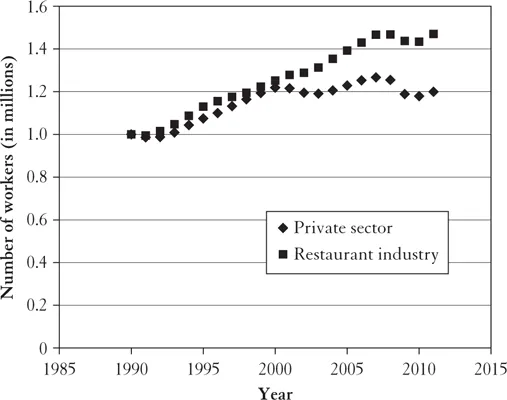

Figure 1. Job growth in the private sector and the restaurant industry, 1990–2011. Adapted from Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, Behind the Kitchen Door: A Multisite Study of the Restaurant Industry, technical report (New York: Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, 2011), fig. 1; http://rocunited.org/blog/2011-behind-the-kitchen-door-multi-site-study/.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics.

I didn’t know it then, but the restaurant industry is one of the largest and fastest-growing sectors of the U.S. economy (see fig. 1). Restaurant workers are not just young people saving money for college or earning a few extra dollars while attending high school (a common misconception among American diners). They are workers of all ages and include many parents and single mothers. Many stay in the industry for 20, 30, or 40 years and take great pride in hospitality.

Unfortunately, although the industry continues to grow, restaurant workers’ wages have been stagnant over the last 20 years, in part because for the last two decades the federal minimum wage for tipped workers has been frozen at $2.13 an hour.3 Millions of workers regularly experience wage theft (not being paid the wages and tips they are owed) as well as discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and other factors, such as socioeconomic background, accent, and educational attainment.

Thus, as soon as the existence of ROC became news, Mamdouh and I were flooded with calls for help from restaurant workers all over New York City—and eventually all over the United States.

Our victory with the owner of Windows on the World made anything seem possible. If we could push him to do the right thing and hire his former employees, then we could get any restaurant to pay higher wages and treat its workers with dignity and respect. As more and more workers called us, I began to feel in my heart that we could radically change the restaurant industry for the better.

ROC grew quickly. We found our own office space and were able to get some funding to hire a small staff. We hired four new people—all former Windows on the World workers. Among our staff of six, I was the only one who had never worked in a restaurant, the only nonimmigrant, and the only person who was not a 9/11 survivor. I was also the only one who had professional organizing experience. I spent many long days training our new staff. I talked about the theory and history of organizing, sharing stories of successful movements from all over the world. I conducted political education sessions on the restaurant industry, labor history, and globalization. I also trained my new colleagues to conduct similar sessions for other restaurant workers so that they could inspire their peers to join us in changing the industry. I remember Mamdouh saying in one of our sessions that he had never thought about workplace discrimination before, but after discussing it with us he could see how all of the restaurants he had worked in maintained racial segregation, with lighter-skinned workers in the front, serving customers, and darker-skinned workers in the back, hidden in the kitchen. He also realized that in his 17 years in the industry he had never seen a white dishwasher in New York City. Dishwashers, who earn minimum wage or less, are almost always the darkest-skinned immigrants or people of color in a restaurant. In fact, of the 4,323 restaurant workers we surveyed around the country, we found that only 6.1 percent of all dishwashers were white.

I learned as much, if not more, from Mamdouh and his former coworkers about the issues workers confront daily in restaurants. During our long days of training we would eat lunch together in different local restaurants. Throughout our meal, Mamdouh would point out things I didn’t know about the service, food, or ambience. He would say, “That’s good service” or “That isn’t.” He would comment if the restaurant was understaffed or if the workers were carrying too much. He would talk about poor management and the problems that arise when workers are expected to live off their tips. He would always say, “If you don’t pay your bill at the end of a meal, the manager will come running after you. But if workers don’t get their tips, they can’t say anything, or they’ll be fired.” I began looking at restaurants differently every time I ate out.

Of course, we weren’t training all the time. We were also busy meeting with the workers who showed up at our door seeking help on the job. Many of them came because they hadn’t been paid. Others had been injured while working. We helped some of them recover their wages and address their problems, but we knew that in order to really begin changing the industry, we needed to engage in high-profile campaigns that would send a signal to other restaurants that poverty-level wages, wage theft, discrimination, and lack of benefits were not sustainable for anyone.

A watershed moment for ROC came about when one of our new staff members, Utjok, visited his brother at a fancy steakhouse in Midtown Manhattan. Utjok met a kitchen worker there who told him that the restaurant had been stealing wages from its employees. He immediately brought the cook to see me. His name was Floriberto Hernandez.

Floriberto was a rotund, jovial Mexican immigrant. He had light brown skin and a baby face that dimpled when he smiled. He always wore a baseball cap. His coworkers, who were also Mexican or Central American, thought he was quite naive, and later told me stories about how they would play mean practical jokes on him. One of the woman workers told me that some of the guys in the kitchen also made inappropriate sexist jokes. For example, they made fun of her for being a little overweight. One day they told Floriberto that she was pregnant. He believed them and congratulated her on the happy occasion. The woman told me that she felt personally humiliated. She was angry with Floriberto’s coworkers and with management for not doing anything about it, but she knew that Floriberto himself was not trying to be mean; he had congratulated her because he was genuinely, though mistakenly, happy for her.

Floriberto wasn’t dumb, just overly trusting perhaps, which is why it hurt him so much when he realized that the company would never pay him and his coworkers their overtime wages without a fight. In fact, Floriberto was probably the most intelligent and courageous of the bunch. When his coworkers shrugged off the wage theft, Floriberto insisted that they do something about it. After coming to ROC and meeting with Mamdouh and me, Floriberto almost immediately brought 17 of his coworkers to our office and started a campaign. He was a true leader.

Floriberto Hernandez with other ROC-NY members on Human Rights Day. Courtesy of Restaurant Opportunities Center of New York.

Over the next two years we launched a public campaign against the restaurant where Floriberto worked, demanding that it pay its workers properly and comply with the law. After all, we argued, a fine-dining steakhouse in Midtown Manhattan should be able to pay basic minimum and overtime wages. After giving the company a chance to respond to our requests for a meeting (and being ignored for several weeks), we organized weekly protests in front of the restaurant. Floriberto and his coworkers joined us. We circled the restaurant, ringing cowbells, beating drums, and of course raising our voices to demand that the company stop the illegal practice of not paying its employees. We handed out leaflets describing the restaurant’s health-code violations to potential customers, and we chanted, “It’s illegal! It’s a crime! Pay your workers overtime!” As the weeks passed, Floriberto convinced more of his coworkers to join the campaign, and a young Latino busser—the only nonwhite waiter in the restaurant—filed charges against the company for giving him the lowest-paying shifts and tables, and for hurling racial epithets at him, even in front of customers.

At one point, we decided to let the restaurant’s customers know what was going on behind the kitchen door. We found out that the restaurant had numerous health-code violations, including insects in the kitchen, food kept out too long, and meat not stored at the right temperature. As the customers entered the restaurant, we passed out handbills that described the nasty things going on in the kitchen. Our latest research shows that in every city across the United States in which we conducted surveys with restaurant workers, the restaurants that mistreated their workers were more likely to engage in unsafe food-handling practices that sicken customers. It made sense—if a restaurant was not a responsible employer, how could we expect that restaurant to be responsible with our health and safety?

The restaurant initially counterattacked, telling the press that our protest was a “shake-down.” I was personally vilified. One columnist wrote an editorial in the Nation’s Restaurant News arguing that we were exploiting 9/11 to change the restaurant industry. In a way, we were. We were using the attention that the Windows workers got to highlight deep problems in the industry that had existed long before the towers fell. The Windows workers had banded together, determined to make the industry better, in the name of their fallen coworkers. The editorial in the Nation’s Restaurant News only strengthened my resolve to stick with the Windows workers and change the industry with them.

Floriberto stood strong, encouraging his coworkers to stay united and not allow the company to intimidate them at work or threaten them with retaliation. His leadership led us to victory. Unfortunately, just as we heard news that the restaurant was going to settle, tragedy struck. I had gone on vacation, accompanying Mamdouh and his family on their annual trip to Morocco. We were in Fez, an ancient city with narrow, winding alleys between old limestone buildings. Late one evening when Mamdouh’s family had already fallen asleep I decided to check my e-mail. I asked a young boy to tell me where I could find an Internet café. He guided me through a dark maze of alleys to a brightly lit room full of computers. Almost the first e-mail I saw was news from home—Floriberto had passed away suddenly. Sobbing, I stumbled through the dark alleys back to the hotel where Mamdouh and his family were sleeping. Mamdouh and I had been fighting that day, but when I told him the sad news, all of our frustrations were washed away in the terrible pain of loss. We found our way to an international phone booth and called the ROC office. Our staff confirmed that we had suffered an incredible loss.

Just a week before, at a protest in front of his restaurant, Floriberto had complained that he was thirsty and tired. He’d brought a huge bottle of Coca-Cola with him to the protest; in fact, over a period of several days he had been buying 20-ounce bottles of Coca-Cola and downing a single bottle in less than a minute. Within a day or two his roommate, a single mother, had found him facedown on the floor of their tiny Bronx apartment. He was a large man, too large for her to move. She called 911. It took four paramedics to lift him onto the gurney and rush him to the hospital. He was in a diabetic coma, apparently having suffered from a sudden adult onset of diabetes. By the time he reached the hospital, it was too late. He had killed himself drinking Coca-Cola.

I immediately threw myself into crisis mode. Floriberto had no real family in the United States, and so...