- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Where Three Worlds Met, Sarah Davis-Secord investigates Sicily's place within the religious, diplomatic, military, commercial, and intellectual networks of the Mediterranean by tracing the patterns of travel, trade, and communication among Christians (Latin and Greek), Muslims, and Jews. By looking at the island across this long expanse of time and during the periods of transition from one dominant culture to another, Davis-Secord uncovers the patterns that defined and redefined the broader Muslim-Christian encounter in the Middle Ages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Where Three Worlds Met by Sarah C. Davis-Secord in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Sicily between Constantinople and Rome

Gregory then set sail from the city of Constantinople, and he reached the city of Rome on the twenty first day of the month of June, and there he worshipped the tombs of the holy and most praiseworthy Apostles, and visited every holy place in the city.… They [Gregory, his father, and ecclesiastical leaders] went on to a ship and left Rome of the sixteenth of the month of August, and reached Sicily on the tenth of September, landing in the city of Palermo. And the bishop of the city of Palermo welcomed them with great honour, surrounded by his clergy and all the citizens and all the monks and nuns.

Leontios, Vita S. Gregorii Agrigentini1

Pilgrims, messengers, administrators, warriors, saints, and immigrants: Sicily’s shores welcomed a wide variety of travelers during the period of Greek dominion. Between Emperor Justinian’s reconquest of the island from the “barbarian” Ostrogoths in 535 CE and the Muslim invasion beginning in 827 CE, the imperial capital at Constantinople was the primary location that sent official travelers—governors, military forces, and envoys bearing news—to the island and received them in reply. It was also the destination of many traveling Sicilian saints and scholars, since the Greek city was the cultural as well as political capital of the Byzantine Empire. But Constantinople was by no means the only location that was closely linked with Sicily through patterns of travel and communication: many individuals, groups, and the goods and institutions they brought with them also arrived in Sicily from other locations of religious, cultural, and political significance throughout the Mediterranean (especially Rome and Jerusalem), thus tying Sicily into larger networks of culture, power, and communication in the early medieval Mediterranean region.2

The ports of Byzantine Sicily, indeed, bustled with ships sailing to and from Constantinople, Rome, Egypt, and North Africa. Muslims, Jews, Latins, and Greeks arrived on the island, at some times for peaceful purposes and at other times for war. The patterns of this travel demonstrate two of the fundamental aspects of the position and role of Sicily within the early medieval Mediterranean: Byzantine Sicily was both a center of political and cultural activity within the region and a shifting, unstable frontier between the three major civilizations of the Mediterranean basin. In these ways, the communication networks in which Greek Sicily was involved reflected many of the larger changes taking place within the early medieval Mediterranean. These were centuries in which Muslims, Latin Christians, Greek Christians, and, to an extent that is hard to quantify in this period, Jews interacted, fought, and shared common cultures, even as political and cultural boundaries in the region were beginning to harden.

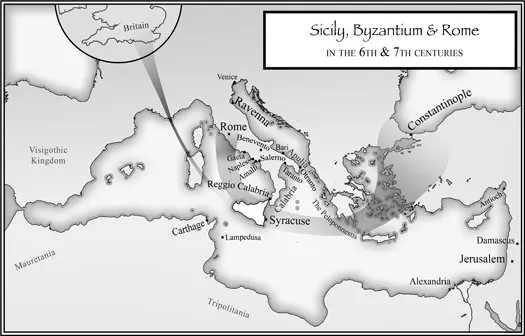

Indeed, Sicily’s geopolitical significance took on new meaning during the later centuries of the Byzantine period, as Muslim naval activity in the area intensified and Byzantium struggled to maintain its borders. Sicily under Byzantine rule operated both as the far western frontier of the empire (especially after the loss of Greek territory in mainland Italy to the Lombards, emphasized by the 751 fall of the Exarchate of Ravenna) and as a center of official communication between Constantinople and the western Mediterranean—particularly, Latin Rome and the emergent powers of Muslim North Africa and Frankish Europe. As the western bulwark of Byzantine power, Sicily was often the focus of intense military and political activity during these centuries. Constantinople was determined to maintain its hold over the island despite the difficulty of such a project when so many forces, both in the western Mediterranean and at home in Asia Minor, worked contrary to this agenda. Diplomatically, too, the Greeks often used the island as a site of political discussions, a source of envoys, or a resting place for messengers traveling from Constantinople to the European mainland. At the same time, Byzantine-controlled Sicily never fully pulled away from the orbit of Rome—the island featured both papal estates and numerous Latin Christian churches—and thus could act as a sort of meeting ground between the two Christian civilizations, which were growing increasingly apart in both administrative and cultural senses, especially after the mid-eighth century (see map 2). After the loss of North Africa to the Muslims in the seventh and eighth centuries, Sicily’s importance to Constantinople was further magnified, even as the imperial government struggled to maintain its hold over this distant island in the face of growing Muslim military and naval dominance in the region. Thus, across the centuries from 535 to 827, the island operated both as a type of physical boundary—although an unstable and incomplete one—dividing the three civilizations of the early medieval Mediterranean and as a locus of cross-cultural communication between them. With ships, goods, information, and people moving between the Greek, Latin, and Muslim worlds via Sicily, the island was the site of overlap and conversation among the three civilizations, just as much as—or even more than—it marked a line of separation between them.

Several categories of travel and communication help to illuminate the system that developed in the central Mediterranean during these centuries. The first, and most prevalent, type of travel to and from Sicily during the Byzantine period was that conducted for political, military, or diplomatic reasons. The abundance of governmental travel in the extant sources is partly a result of the preservation of certain types of texts relating to the Byzantine centuries and partly due to the interests of those sources. Latin papal letters and Latin and Greek chronicles reveal diplomatic and military travelers tasked with maintaining or restoring order in the empire’s territories in Italy, negotiating with the popes in Rome, or, as we will see further in chapter 2, settling peace treaties with Muslim North Africa.

MAP 2. Sicily, Byzantium, and Rome in the sixth and seventh centuries

A second kind of traveler in the Byzantine Mediterranean world was those people who took to sea in the course of their religious careers, spiritual pilgrimages, and intellectual pursuits. A number of such travelers went to or through Sicily on their journeys to Rome, Jerusalem, or Constantinople, while others were born and raised on the island and traveled toward the intellectual and religious capital at Constantinople in order to advance their careers. Greek hagiographies from Sicily and southern Italy record the lives and deeds of Greek saints from the region, as well as their travels throughout the Mediterranean world. These hagiographical sources are particularly numerous for the ninth and tenth centuries, and they therefore provide instructive anecdotes about individual interactions between Greek monks and Muslim invaders to Sicily, such as monks who sailed on Muslim ships as captives or those who defended their lands against the Muslim raiders by miraculous means. Early medieval Latin pilgrimage accounts, papal letters, and papal biographies also inform us about travelers to Sicily from Europe.

A third type of travel was that which connected Sicily to broader economic networks within the Mediterranean system. Virtually none of the extant sources from this period directly pertain to commerce or the shipments of the grain annona.3 Because this type of activity is so rarely represented in the surviving source material from the Byzantine era, definitive conclusions are impossible to establish. Interest in Sicily’s contribution to the early medieval Mediterranean economy is persistent, however, particularly because of its historical status as a major source of grain for the Roman Empire. Nonetheless, as Michael McCormick has argued, it is possible to assume that shipments of merchandise hovered just below the surface of the travel for which we do have records: that is, for every sea voyage of a saint, official, or pilgrim, we might presume that an entire shipload of unrecorded mercantile products made the voyage as well. The bulk of the travel that we can trace may not have been explicitly economic, but it may imply economic exchange that would have taken place along similar routes and on the very same ships. Still, Sicily’s economy in the Byzantine period is impossible to fully understand, and we are left with more questions than answers.

Political, Diplomatic, and Military Connections to Constantinople

After Sicily was politically united to Constantinople in the sixth century—as part of Justinian’s efforts to regain the lost glory of Rome by means of conquest in the western Mediterranean—it initially held the status of a provincia and was governed by a praetor, a civil provincial official in charge of local security, finances, and judicial affairs.4 However, in the late seventh century, the island was designated a theme—a major military and territorial unit of the empire—after which time it was ruled by a stratēgos, a military general also responsible for financial and judicial administration.5 Status as a theme raised the importance of Sicily within the empire, and particularly within its western regions.6 At some point in the eighth century, Constantinople also took direct control of the ecclesiastical administration of Sicily, transferring it from the jurisdiction of Rome to that of the patriarch of Constantinople. Sicily’s status as both a military and an ecclesiastical province necessitated a high level of communication between the island and the empire’s distant capital. Given that most of the imperial holdings in the West would fall away over the course of the seventh and eighth centuries, maintaining control of Sicily was of high importance to Constantinople, even when that proved to be difficult, and therefore the patterns of communication between the two locations emphasize the island’s significance in the empire.

Constantinople was an imperial capital that lay at a considerable distance from Sicily—roughly 1,300 nautical miles, depending upon the route taken—meaning that communication between the two places was a serious undertaking that necessitated a long and potentially dangerous journey by sea.7 Nonetheless, the emperors at Constantinople regularly dispatched administrative officials and military forces to the island—even, sometimes, when the capital was under siege. This type of political communication between Sicily, as the province, and Constantinople, as its imperial capital, took place for a wide variety of reasons—from military actions and the suppression of rebellions to administrative updates, the transmission of important news, and personnel replacements.8 Armies, naval fleets...

Table of contents

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Timeline

- Introduction

- 1. Sicily between Constantinople and Rome

- 2. Sicily between Byzantium and the Islamic World

- 3. Sicily in the Dār al-Islām

- 4. Sicily from the Dār al-Islām to Latin Christendom

- 5. Sicily at the Center of the Mediterranean

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index