- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this account of one of the worst intelligence failures in American

history, James J. Wirtz explains why U.S. forces were surprised by the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive in 1968. Wirtz reconstructs the turning point of the Vietnam War in unprecedented detail. Drawing upon Vietcong and recently declassified U.S. sources, he is able to trace the strategy and unfolding of the Tet campaign as well as the U.S. response.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

“THE BIG VICTORY,

THE GREAT TASK”

[1]

The Communist Debate over Strategy

One of the many questions about the Vietnam War that remains to be settled is why the North Vietnamese decided to launch the Tet offensive. The question is intriguing because the communist offensive was both a dismal military failure and a brilliant political success. The U.S. military quickly recovered from the surprise it suffered and decimated the Vietcong (VC) forces that bore the main burden of the attack. In the aftermath of the offensive, however, the American public and the Johnson administration seriously questioned the costs and objectives of the war. In this respect, the Tet offensive acted as a catalyst, setting in motion a chain of events that would lead to negotiations, a halt in the bombing of North Vietnam, and a deescalation of the U.S. combat role in South Vietnam. “Tet did not end the war for the communists,” according to Richard Betts, “but it created the necessary conditions for political victory.”1

Although students of the Vietnam War do not dispute the military outcome of the Tet offensive or its political impact, they have not achieved a consensus about the attack’s objectives. Two interpretations of communist goals have dominated the debate. The first maintains that the shift created in American public and elite opinion was an intended rather than an unintended consequence of the offensive. Many leading commentators on the war, for example, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the commander of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) at the time of the offensive, Col. Harry G. Summers, Leslie Gelb, and Richard Betts, claim that the attitudes of the American public and members of the Johnson administration were the ultimate targets of the offensive.2

The second interpretation maintains that an improvement in the military situation or even the immediate domination of South Vietnam was the primary objective behind what the communists called their “general offensive-general uprising.” Stanley Karnow, for example, notes that, at a maximum, the communists hoped to overthrow the Saigon regime and replace it with a neutralist coalition dominated by the VC. Once in place, the new regime would work to eliminate U.S. presence and put Vietnam on the path to unification under communist control. U. S. Grant Sharp, former commander in chief, Pacific (CINCPAC), believes that the communists intended to destroy the South Vietnamese administrative structure so that it would no longer function even with U.S. aid. Sharp also notes that the North Vietnamese hoped for a large-scale defection of South Vietnamese troops, facilitating the communist domination of large portions of the country. According to Patrick McGarvey, Tet was intended to improve the position of the North Vietnamese in future negotiations by placing the two northernmost South Vietnamese provinces under communist control, setting the stage for the eventual domination of the country.3

Neither of these interpretations is particularly compelling. The first is misleading because it ignores the probable existence of a communist theory of victory and seems to suggest that the North Vietnamese expected to tip the political scales in their favor just by demonstrating their willingness to stand up to their opponents’ firepower. It fails to account for any realistic North Vietnamese military objectives, the logical prerequisite for an effort to influence American opinion. In contrast, the second explanation, which focuses on the military objectives of the offensive, fails to acknowledge the deteriorating situation faced by the North Vietnamese and VC forces on the eve of Tet. Moreover, both interpretations largely ignore the insights into communist objectives offered by the concept of a “people’s war,” especially the Vietnamese version of this strategy.4

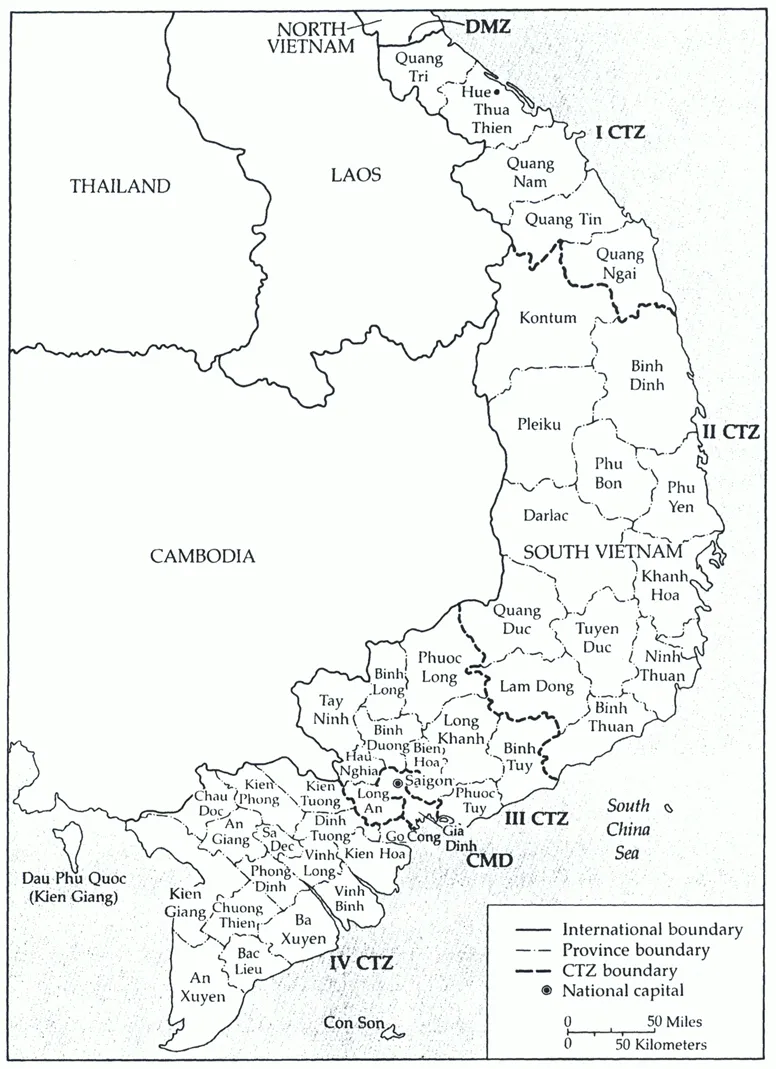

SOUTH VIETNAM

My purpose in this chapter is to examine the communist debate over strategy that led to the Tet offensive. For two years before the decision to launch the offensive, a bitter debate took place among communist military leaders over the appropriate tactical and strategic response to U.S. intervention in the ground war in the south. As communist leaders witnessed the erosion of their hard-won military gains during successive compaign seasons, they were unable to select a strategy to overcome the strengths of, and take advantage of the weaknesses of, their new opponents. Throughout the course of this debate, though, a slow but steady movement toward the strategy and tactics of the Tet offensive can be detected.

My examination of this communist debate illustrates three aspects of the decision to launch the Tet offensive, aspects largely overlooked in previous analyses. First, the decision was probably motivated by a desire to end a divisive military debate over the proper response to U.S. intervention; an offensive that utilized the entire range of military assets in the south would serve to appease all sides in the strategy debate by incorporating everyone’s pet project and military organization. Second, the decision was motivated by the military leadership’s perception that they were no longer making significant progress toward the unification of Vietnam under communist rule; both the North Vietnamese and VC leadership realized that, if current military trends continued, they would eventually lack the resources needed for an offensive strong enough to affect the military situation in the south. Finally, the examination of the debate over strategy demonstrates that the Tet offensive was the first major initiative adopted by the communists in response to U.S. intervention in the ground war. The communist leadership hoped that Tet would actually win the war in the south. At worst, they probably expected that the attacks would stop the momentum of allied offensive operations, buying the time needed to lay the groundwork for an extended war of attrition.

THE VIETNAMESE APPROACH TO PEOPLE’S WAR

Throughout the war, U.S. observers failed not only to recognize the martial traditions that influenced the communists’ conduct of the war but also to understand their opponents’ military strategy. Speaking years after the conclusion of the conflict, Gen. Phillip Davidson, chief of MACV intelligence during the Tet offensive, remarked that “the great deficiency of our entire operation . . . was [that] we really didn’t have any experts on Vietnam who could tell us about these things.”5 To an extent, Americans can be forgiven for this shortcoming. Couched in convoluted terminology best understood by cadres long schooled in Marxism-Leninism, communist military writings did more than just communicate the latest twist in military strategy emanating from Hanoi; the rhetoric created by communist strategists also was meant to have a political impact by bolstering morale among their forces in the south and by winning the global propaganda battle. U.S. intelligence analysts failed to understand their adversary because they focused on only two aspects of their opponent’s strategy: the Vietnamese application of people’s war, which relied heavily on the ideas articulated by Lin Piao and Mao Tse-tung; and the military aspects—especially military operations involving conventional units—of the communist effort to unite Vietnam.6

Although the Soviets exerted a strong influence on the Vietnamese communists during the 1930s, the three-phase strategy of people’s war devised by the Chinese communists eventually provided a framework for communist activities in South Vietnam. In phase one of the Chinese plan, the insurgents remain on the defensive but attempt to establish control of the population and conduct terrorist and guerrilla operations. In phase two, regular military forces are formed, the tempo of guerrilla activity increases, and isolated government forces are engaged. In the final phase, the insurgency is victorious as large military units, organized along conventional lines, go on the offensive, destroying the government’s forces and establishing full control of the population.7

The Vietnamese, however, developed their own version of people’s war. They succeeded, according to Douglas Pike, in devising a strategy that eliminated the distinction between soldiers and civilians, uniting both in the dau tranh (struggle) against the enemy. Everyone was to participate in at least one of the two prongs of people’s war: dau tranh vu trang (armed struggle, or “violence program”) and dau tranh chinh tri (political struggle, or “politics with guns”). Political action was directed against three specific targets. Dich van (action among the enemy) was intended to undermine support for the war among the population in enemy-controlled areas—to win the propaganda war for the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese and for the sympathy of the American public. Binh van (action among the military) was at a minimum intended to undermine morale in the opponent’s army, thereby reducing its effectiveness in combat. At a maximum, the communists hoped that binh van would cause South Vietnamese soldiers to defect to the communist side, or even to defect in place by supplying weapons and information about allied military operations to the VC. Dan van (action among the people) was to bolster support for the cause in communist-controlled areas in order to harness the man power and material resources these regions could supply.8

Although the proper mix of armed and political struggle in each phase of people’s war was often the subject of intense debate within the communist hierarchy, the intensity of both activities was intended to increase as the battle moved toward the culmination of phase three: the general offensive–general uprising. The phrase is appropriate: the general offensive implies overwhelming military pressure; the opponent is subjected to the full force of the conventional units that have taken the field during the third phase; the general uprising is the culmination of years of political dau tranh. As envisioned by the Vietnamese, thousands of civilians would burst onto the streets of the cities and villages of South Vietnam in an outpouring of revolutionary fervor. Joined by individual defectors from the South Vietnamese army or even entire units, the general uprising would sweep the Saigon regime from power.9

The concept of a general uprising represents the major Vietnamese contribution to the theory of people’s war. Historically, the Vietnamese had employed this tactic against Chinese rule at least ten times before C.E. 940. In more recent times, they also fostered a mass revolt against the French in the August uprising of 1945 and against the South Vietnamese regime in 1959 and 1960. In fact, during the 1960 uprising the communists timed their attacks to coincide with the Tet holidays, imitating a precedent set by Nguyen Hue when he led a surprise attack in 1799 against the Chinese occupiers of Hanoi. The decision to launch a general uprising against U.S. forces was, however, a point of contention within the communist hierarchy. Timing (thoi co, or “opportune moment”) was crucial. If military and political conditions were not favorable, efforts to launch a general offensive–general uprising could end in disaster. Still, the communists believed that this was their ultimate weapon.10

Although in hindsight it might appear that the communists attained their objectives by simply progressing through each phase of people’s war, in fact their strategic decisions often involved heated debate. Differences of perspective between northern and southern communists often served as a source of tension. Both the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), initially established in 1951 as the communist military headquarters in South Vietnam, and the southern branch of the Vietnamese Worker’s (communist) party (VWP), the People’s Revolutionary party (PRP), established in 1962, were created to prevent southerners from straying from the political and military line set by the regime in Hanoi. A “Red vs. expert” debate also flared among officials in Hanoi. Faced with an opponent that possessed advanced weaponry and huge material resources, military and political leaders constantly debated whether ideological purity and revolutionary z...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I: “The Big Victory, The Great Task”

- Part II: The Origins of Surprise

- Conclusion: Explaining the Failure of Intelligence

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Tet Offensive by James J. Wirtz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Guerre du Vietnam. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.