| 1 | | FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC IN HONG KONG |

Sundays in Central District are a spectacular sight. There in Hong Kong’s most celebrated financial district, amidst awesome high-rise structures, towering hotels, and dwarfed colonial government buildings, crowds of domestic workers, mainly from the Philippines, but also from other regions of South- and Southeast Asia, gather to socialize, to attend to personal matters, and to escape the confines of their employers’ homes and their mundane weekly routines of domestic work.

On Sundays in Central the noise is louder, the colors brighter, and the crowds more overwhelmingly female than on other days of the week. Filipinas who gather in Statue Square on Sundays and public holidays have been described as “one of the most colourful and cheerful features of life in Hongkong” (Donnithorne 1992), “the vibrant colours of their plumage . . . as striking to the eye as their incessant chatter is to the ear” (Flage 1987). Foreign domestic workers line the sidewalks and elevated walkways that connect the Central Post Office to the Star Ferry and Blake’s Pier, and they gather in groups under the shade of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank—one of Hong Kong’s most famous capitalist monuments—across the road from the square. On hot and steamy summer days, scores of women cluster under the trees in Chater Garden, along Battery Path, and in the parking lots and roads leading up toward Saint John’s Cathedral, Hong Kong Park, and Government House. Along Chater Road, which is closed to traffic on Sundays, they sit in the shadow of five-star hotels and designer boutiques, picnicking on straw mats, blankets, or newspapers, contributing to the festive atmosphere.

The crowd, though it might look to outsiders like random clusters of dis-array, has a clear logic to those who are familiar with it. Domestic workers of different nationalities regularly congregate in specific locations. Many women from South Asia—India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka for example—gather in parks and gardens along the edge of Tsim Sha Tsui and Tsim Sha Tsui East, across the harbor from Central District in Kowloon, the region where many of their South Asian employers live and work. Women from Southeast Asia—Thailand, Malaysia, or Indonesia—are more likely to be found in Central District along the waterfront parks near the Central Post Office and Blake’s Pier. By the late 1990s, Victoria Park in Causeway Bay had become the main place for Indonesians to congregate and Muslim domestic workers of many different nationalities clustered near Kowloon Park and the Kowloon Mosque. Filipinas have long clustered mainly in Statue Square, along Chater Road, in Chater Garden and up the hill toward Hong Kong Park. Different Philippine regional and dialect groups occupy different parts of Central District. Ilocanos, for example, congregate under the pavilion behind the “black statue” and those from Nueva Vizcaya are under the northeastern pavilion. Increasingly, they also congregate in parks and public spaces that are closer to the places where they live and work, in Kowloon and in the New Territories (a 398-square-mile region that adjoins mainland China).

On other days of the week one also finds dozens or even hundreds of domestic workers in Central, and especially in the square, but only a fraction of the Sunday crowd. On weekdays there are those who are allowed to go out after they finish their work, others who are permitted to stop by the square on their way to or from an outing with their charges, and mainly those who have been assigned a day other than Sunday as their rest day. Although a domestic worker has little choice but to accept whatever rest day her employer assigns, a day off other than Sunday is considered unfortunate, a conscious ploy on the part of the employer to keep a worker “in the dark” and away from friends and relatives, most of whom have Sundays off. A different day off means a worker cannot meet friends as easily or attend church or other worship services. Nor can she participate in migrant organizations, such as regional “circles,” clubs, or Philippine associations, or join in the rallies or informational drives organizedby the Asian Domestic Workers Union, United Filipinos in Hong Kong, and other groups.

On Sundays there is an unmistakable tide of Filipinas on all forms of public transportation that heads toward Central from the far corners of Hong Kong and the New Territories. They create a festival atmosphere that transforms the place. On weekdays there is less going on in the square, and the domestic workers who go there are counterbalanced by tourists and by local Chinese and westerners who also work, shop, and eat in Central District. But on Sundays, as one Filipina described it with a sigh, Central becomes “a corner of the Philippines transplanted into Hong Kong.” Teddy Arellano, a staff member at the Asia Pacific Mission for Migrant Filipinos, described it: “Statue Square has become a haven for migrant workers from the Philippines and other countries. Especially for Filipinos, it has become . . . their ‘Home away from home.’ As they congregate, it brings back a slice of life from our country, which in a way alleviates their loneliness and homesickness. It has become an emotional blanket for many as it fortifies and recharges them from the rigours of the week’s work” (Arellano 1992). A Hong Kong Filipino newspaper advises those who feel lonely to go to the square. There, “you can feel you’re right in Luneta, Quiapo or Divisoria. News, gossip, magazines, komiks, pirated audio tapes and even designer clothes, these and more are available there. If you want to eat adobo, pinapaitan, dinakdakan, paksiw, halo-halo and ginataan, it’s there. . . . If you like to gamble, this is your place; pusoy, shohan, black jack, 41, Lucky 9 and—believe it or not—jueteng!” (Madamba 1993:56).

THE BATTLE OF CHATER ROAD

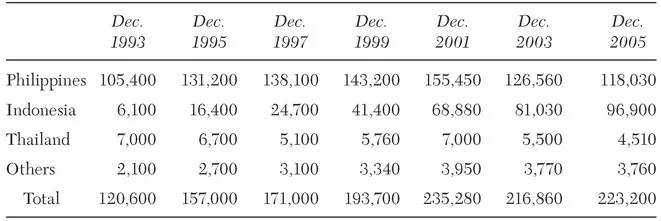

The weekly transformations of Statue Square point to some striking changes in Hong Kong’s social demography over the past three decades. Since the late 1970s, few full-time, live-in domestic workers have been Chinese; the vast majority of them have come from outside the colony. Local Chinese women and recent legal and illegal immigrants from mainland China do such work, increasingly so in the late 1990s, but mostly part-time, and they tend to “live out” (i.e., they do not reside with their employers). The numbers of the informal local labor force are difficult to estimate and often go unreported. Yet it is safe to say that the vast majority of domestic workers in Hong Kong are foreign women. Of the over 150,000 foreign domestic workers in 1995, about 95 percent were women, and over 130,000 were from the Philippines, making Filipinos the largest non-Chinese ethnic group in the colony.1 In 1993 domestic workers from Thailand were the second largest group, numbering approximately 7,000, followed by 6,000 workers from Indonesia, and smaller numbers from Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Burma, Nepal, and Vietnam (Table 1.1). In the following decade, significant shifts occurred. By 2005, there were officially over 220,000 foreign domestic workers overall, up from over 120,000 in 1993. Hong Kong Immigration Department figures indicate that the number of Thai domestic workers decreased slightly over the next decade, while the number of Indonesian domestic workers continued to grow, reaching close to 100,000 in 2005, as the numbers of Filipinas briefly dropped to below 120,000 then rose to around 124,000 in 2006.

TABLE 1.1 Number of Foreign Domestic Workers in Hong Kong, 1993–2005

Source: Hong Kong Immigration Department.

In the mid-1980s and early 1990s, as the number and visibility of Filipina domestic workers rapidly increased, so did complaints about their “takeover” of Central District, and critiques began to appear in the local newspapers (e.g., South China Morning Post [SCMP] 1986b, 1990; Hongkong Standard [HKS] 1986; Yeung 1991). A contentious public debate arose in the autumn of 1992 and early 1993 when Hongkong Land, Central District’s leading landlord, suggested that the government reopen Chater Road to traffic on Sundays. This marked the beginning of what was dubbed the “Battle of Chater Road” (Tyrell 1992), fought in bellicose words. One editorial announced that Filipinos “are guest workers here with no ‘divine right’ to commandeer Central for their own use” (Mercer 1992, emphasis added). Others accused foreign workers of having “invaded,” “overrun,” or “taken over” parts of Central, thus preventing others from using it.

Ironically, Hongkong Land had initiated the original petition to close the road to vehicular traffic ten years earlier on the grounds that a traffic ban would encourage pedestrian shopping. They had also cosponsored some of the concerts and competitions designed to attract people to the area. The reasons Hongkong Land spokespersons gave for their change of heart were the “environmental problems” posed by the influx of domestic workers to the area, “undesirable activities” such as gambling and hawking, and the “continual complaints” they received from their hundreds of tenants in the area about “restricted access,” crowds, and noise (Wallis 1992a). According to Hongkong Land, reopening Chater Road on Sundays would allow tenants to load and unload trucks, discourage the crowds of foreign workers from congregating there, decrease the congestion in the area, and thus encourage another “class” of people to come.

The eighteen-page report Hongkong Land submitted to the Central and Western District Boards included complaints from tenants who said off-duty foreign workers were giving “one of Asia’s most glamorous shopping areas the appearance of a slum” and described the area as “a nightmare with the atmosphere of a third-rate amusement park.” Other tenants disapproved of the “littering and messy situation . . . created by the maids” who congregate outside Alexandra House and the Princes Building, and declared their preference for “yuppies” and “quality families” who might go to such posh places to spend money. Another tenant wanted “more business, not Filipinos loitering around and creating all kinds of nuisance” (Wan 1992; AMC 1992b:24).

Such statements were widely criticized for their implicit or explicit racism. Another common reaction—largely from Western expatriates—was that Hong Kong people should “clean up their own backyard” before pointing the finger at Filipinos and that the litter in Statue Square is no worse than that left at train stations at Chinese New Year or at country parks on weekends (Atkinson 1992; R. Chan 1992; Hardie 1992). Others criticized the government for “not providing adequate manpower and resources” to deal with the illegal hawking, gambling, and six tons of litter reportedly “left by off-duty Filipino domestic workers in and around Chater Road each Sunday” (Wallis 1992d).

Individuals and organizations had already been seeking alternative venues and ways to “lure” domestic workers from parts of Central well before the autumn of 1992.2 But Hongkong Land’s proposal set off a new tidal wave of complaints about domestic workers and their use of Central District, and an equally vehement barrage of letters by and in defense of Filipinos. Among the flood of opinions aired in the local newspapers, Arthur Tso Yeung’s was fairly typical. Like many, he considered foreign domestic workers a public nuisance that deprived others of their right to spend Sundays in Central. Yeung “applaud[ed] Hongkong Land for taking such a bold step in recommending a halt to this ridiculous arrangement which the majority of us have had to put up with for the past ten years.” Furthermore, Yeung asked, “has it been ten years now since we have been deprived of the use of Statue Square? I wonder what the British and Americans would say if Leicester Square or Times Square were sealed off every Sunday for converging crowds of Chinese to gather to gamble, hawk, and exchange black market foreign currencies and generally to deface the vicinity” (Yeung 1992).

P. K. Lee reiterated the view among many Hong Kong Chinese that “maids” deprive others of access to the “inner Central area.” He wrote, “This small area in Central becomes effectively out of bounds on Sundays to the local Chinese, as it is virtually impossible to move about and the facilities such as toilets are impossible to enter. . . . Maids sitting on footpaths and roads should be asked to quickly complete whatever business they may have and move along so that others can use the facilities.” Lee recommended a solution: “Most maids would welcome the opportunity to do part-time work on Sundays: the Government could solve this problem by simply allowing them [to] work” (Lee 1992; see also Mercer 1992).3

Some, such as A. R. Hunt (1992) and David Granger (1992), responded that the square is open to everyone and that no one was preventing Yeung or Lee from going there. Others pointed out that reopening Chater Road would not prevent domestic workers from going to Central and that the most constructive approach would be to provide other sites for domestic workers to use (Madamba 1992; T. Giles 1992). Some readers criticized the proposal to create special sites, however, as giving Filipinos special treatment that permanent Hong Kong residents did not receive. Arthur Tso Yeung asked, “Why should any particular foreign minority group be granted any special favours in any particular area?” (1992).

Hongkong Land proposed as a “constructive” approach to the problem of congestion in Central District that underground car parks could be offered as gathering places for domestic workers on their days off. The leader of a Rotarian group who had been working on alternative sites for carnivals and other activities to attract domestic workers away from Central criticized the suggestion, declaring that the noise would disturb the neighborhood and that domestic workers would not be attracted to car parks (Wallis 1992b). Many letter writers expressed horror at the “car-park suggestion” and called it “inhuman” (e.g., Chugh 1992; Palaghicon 1992). Some went so far as to point out parallels between “ethnic cleansing” in Eastern Europe and “proposals to herd Filipinos into underground car parks to create leisure lebensraum for ‘locals’” (Marshall 1992; Free 1993).

Filipinos saw the proposal as yet another attempt to keep domestic workers “out of sight,” akin to rules that force them to use back entrances to buildings and confine them to certain waiting areas in elite clubs (AMC 1992b:24). Staff at the Asian Migrant Centre pointed out that such restrictions reflect the insulting way in which domestic workers are “persecuted, segregated and pushed out of visible social life.”4 In Hong Kong these workers are “needed, yet needed out of sight.” The AMC asked, “Is it right for power to be wielded towards alienating sections of people in society and pushing them somewhere less conspicuous and more convenient, especially when these very people help the wheels of society run smoothly?” (AMC 1992b:24).

Given the number of letters that Filipinos sent to the local papers over other issues, it may seem surprising that relatively few Filipinos wrote on the issue of Chater Road (exceptions include Arellano 1992; Madamba 1992; Palaghicon 1992). Yet as several Filipinas pointed out to me, their verbal response was not nearly as significant as their actions. The domestic workers who came and sat in the square and along Chater Road, passing around copies of the letters and editorials that were printed in the local newspapers, expressed their sentiments in more embodied ways, and thousands of domestic workers continued to gather in Central on Sundays, laughing, talking, and eating en masse. They demanded to be seen, and they refused to be moved. By 2006 the Battle of Chater Road was long forgotten. The area surrounding Statue Square, still filled with Filipinas on their day off, had become, as Hongkong Land had first imagined, a tourist attraction and a well-accepted part of the urban landscape.

RESEARCH ON DOMESTIC WORKERS

Before returning to the situation in Hong Kong, it is important to place this book in relation to other work that has been done on paid “household workers.”5 In the late 1980s Henrietta Moore observed that household work “is an area of waged employment which is very much under-researched” (1988:85–86). Since the 1960s, however, in the wake of the civil rights and women’s movements in the United States, the body of anthropological, sociological, and historical literature has grown steadily. Many of these studies are rich in historical and ethnographic detail, which illustrates the multiplicity of regional variations in the patterns of household work—the employer-worker relationship, work conditions, and the treatment of and attitudes toward the worker. Cumulatively, whatever the intentions of individual authors, they constitute an argument against “modernization” approaches that posit u...