1

STUDYING WAR, STATES, AND CONTENTION

In 1659, toward the end of the Puritan Revolution, army officers sent Parliament a petition demanding an increase in the military budget. The members of Parliament (MPs) refused to act on their demand and voted a ban on soldiers holding meetings without government permission. In response, troops entered London, where they encamped until a new rump parliament was called. Richard Cromwell, the successor to the Puritan Commonwealth his father had founded, was too weak to deal with the army’s actions and was forced to resign. When he eventually slunk off to France, the heir of the Stuart line, Charles II, awaiting his chance in Holland, returned in temporary glory. The Puritan Revolution was over.

It was in this atmosphere that Samuel Pepys, master diarist, sent a description of the melee he had witnessed outside Westminster between City apprentices and soldiers to his patron, Lord Edward Montague (Tomalin 2002, 74–75). On December 5, the apprentices brought a petition calling for “the removal of the army from their streets, so that ‘a rising was expected last night, and many indeed have been the affronts offered from the apprentices to the Red-Coats of late.’” The government responded with a proclamation prohibiting “the contriving or Subscribing of any such petitions or papers for the future” (quoted in Tomalin 2002, 74–75). In response to the threat of the apprentices, many more soldiers, foot and horse, were sent to the City:

The shops were shut, the people hooted at the soldiers…. boys flung stones, tiles, turnips &c…. some they disarmed and kicked, others abused the horses with stones and rubbish they flung at them…. in some places the apprentices would get a football (it being a hard frost) and drive it among the soldiers on purpose, and they either darst not (or prudently would not) interrupt them; in fine, many soldiers were hurt with stones, and one I see was very near having his brains knocked out with a brickbat flung from the top of an house at him. On the other side, the soldiers proclaimed the proclamation against any subscriptions, which the boys shouted at in contempt, which some could not bear but let fly their muskets and killed in several places…. (Pepys to Edward Montagu, December 6, 1659)1

Readers may think it odd to begin a book on war, states, and contention in the modern world with a brief conflict between apprentices and soldiers in early modern England. But Pepy’s story reveals the factors that were already linking war-making, state-building, and contention in the seventeenth century. Consider what was happening in the story:

- the army attempted to militarize the Puritan Commonwealth;

- the government was asked to raise taxes to keep it afloat and satisfy the army’s needs;

- Parliament, with an eye on its members’ financial interests, was reluctant to vote these taxes; and, finally,

- political contention between the apprentices and the soldiers forced Parliament to give way to the army over financing the state’s ability to make war.

The story also suggests how a state’s center of hierarchical power—the military—clashed in times of tension with the MPs in Parliament and with politics in the street—both of which tried, unsuccessfully, to rein in the army. It also tells us how contentious politics—in the clash between the apprentices and the army and between the army and Parliament—was the spur for a major change in the emerging English state (Porter 1994, 83). And, finally, it hints at the future development of what I call the national security state, the employment of emergency measures against contentious actors in times of war or domestic turbulence.

This time, it was the army that won, setting back the constitutional monarchy for three decades. But another war, brought on by the Catholic convictions of the returned monarch, spurred Parliament to bring Protestant William and Mary to England in a Glorious Revolution that established Parliament’s power and sent the army to the barracks (Brewer 1990). Yet, when we remember the Puritan Revolution, we tend to think of religion and neglect the intersections among war, state-building, and domestic contention that led to these changes. Those are the relationships that I set out to examine in this book.

One reason for this gap in our understanding is that we tend to see war in isolation from domestic contention. “Traditionally,” notes Mary Dudziak, “this distortion has been tolerated because wars end” (2010, 4). But do wars end quite so neatly? England was almost constantly at war from the Civil War that began in 1640 until the end of the Commonwealth, and these wars were accompanied by almost constant internal struggle. Following the French revolution, the new state was at war almost uninterruptedly from 1792 until Napoleon’s defeat. And the United States was at war for more years than it was at peace through much of the nineteenth century.

Not only that. Since the Spanish-American war of 1898, U.S. wars have become ever longer. While the war against the Spanish lasted for one year, Americans fought for two years in World War One; for four in World War Two; for thirteen from the beginning of involvement in Vietnam to the evacuation of the last G.I.s from Saigon; and for nine in Iraq, twelve in Afghanistan, and thirteen in the War on Terror since 2001. If we consider the Cold War as a real war, which in terms of military mobilization it certainly was (Griffin 2013, 67–68; Hogan 1998, 60), the average length of U.S. wars becomes even longer. “In the twenty-first century,” Dudziak continues, “we find ourselves in an era in which wartime—the war on terror—seems to have no endpoint…. how can we end a wartime when war doesn’t come to an end?” (2010, 4).

Why is it important that wars have grown longer over time? One reason is that it has given enormous power to what President Dwight Eisenhower called “the military-industrial complex” (Weiss 2014). Another is that it created a national security state whose grip on civil society was only heightened by the events on September 11, 2001 (Posner and Vermeule 2005). But a third, less obvious reason is that the longer wartime lasts, the more likely it is to overlap with “normal” politics and thus to reshape domestic contention.

In part 1 of this book, I will show that movements have long been involved in aiding and abetting war-making, in mobilizing citizens to support—or to oppose—the government, and in profiting from political opportunities that arise in war’s wake. In part 2, we will see that in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries social movements have become major players in episodes of war. Indeed, these composite wars have pitted movements against states in sequences of interaction, repression, and sometimes open warfare. And increasingly, movements have crossed borders to escape repression and in pursuit of their claims. In response, states have learned to use international institutions to pursue them, as I will show in part 3. Intranational, transnational, and international conflicts have become increasingly imbricated in the long wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

If movements are so deeply imbricated with war-making and with changes in the state, we might expect to find a rich literature on the relations among war, state-building, and contentious politics. Alas, we do not. Students of international relations have seldom investigated the relations between domestic and international conflict; students of domestic politics give little attention to the effect of war on contentious politics; and although there is a rich literature on antiwar movements among scholars of movements, these almost never examine how movements lead to war, how movements support war-making, and how war affects contention in war’s wake. This book sets out to fill that gap.

Relations between war and state-building have received more attention than the relations between war and movements. Charles Tilly, whose historical work on the origins of the Western state was the inspiration for this book (1985, 1992a), found resistance to war in the form of tax revolts, anticonscription riots, and refusals to house soldiers or provide armies with subsistence. Modern states, he argued, were born when elites fought neighbors over territory. To do so, they hired civil servants and professional soldiers and extracted resources from their citizens. Extraction, the quartering of soldiers, and the occupation of borderlands led massively to contention: “The organizational structures of the first national states to form [i.e., in Europe],” writes Tilly, “took shape mainly as a consequence of struggles between would-be rulers and the people they were trying to rule” (1992a, 206–7).

Extracting resources from the populace led to conflicts that could be resolved in only one of two ways: by becoming a coercion-rich state that subjected people to harsher internal rule or by according them privileges that became the sources of citizenship (Tilly 1992c; see also Tilly 1986, 2004). Those privileges gave citizens the protection they needed to produce war materiel and the political resources they could use to engage in contention. War, for Tilly, was not only the origin of state-building, but of citizenship, and in the grudging extension of rights to citizens lay the origins of contentious politics. But not even Tilly did more than gesture at the complex and shifting relations among war, state-building, and contentious politics.

In this book, I attempt to fill this gap. Drawing on three scholarly traditions—social movements and contentious politics, comparative-historical analysis, and international relations, I will show that war and contention are inextricably related to one another and that both of these intersect with state-building and state transformation.

Social Movements and Contentious Politics

The major actors in contentious politics are social movements—“collective challenges, based on common purposes and solidarities, in sustained interaction with elites, opponents, and authorities” (Tarrow 2011b, 9).2 Movements arose in conjunction with the consolidated national state and spread across the globe alongside imperialism, mass literacy, and industrialization (Tilly 1984). Movements have long had a close relationship to war-making through nationalism, civil war, guerilla insurgencies, and antiwar campaigns. Each of these variants has given rise to its own scholarly literature, often with little connection to the others, but all are part of a broader relational field I call contentious politics.

By contentious politics I mean episodic, public, collective interaction among makers of claims and their objects when at least one government is a claimant, an object of claims, or a party to the claims and the claims would, if realized, affect the position of a least one of the claimants (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001, 5). It might be objected that all forms of politics include contention, but this is actually untrue; processes such as financial exchange, licensing, celebrating, and passing routine legislative enactments are part of politics but are not normally contentious. Congressional debates and elections are contentious all right, but they are not nonroutine.

It might also be thought that contentious politics is another term for social movements, when it actually refers to the field of interaction among collective actors or those who represent them, whether they are social movements or not. The term does include movements, but it also includes contention between striking workers and their employers, insurgent armed forces and their governments, the contestants in civil wars, and revolutionary coalitions and the states they strive to overthrow. The distinction is important because it is often actors other than movements that support war-making, such as the U.S. civil society groups that rallied around entry into World War One; oppose it, such as the Italian Socialist Party that did so in the same period; or the military or police, such as the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) that supported the Protestant side against Catholic insurgents in the Northern Irish “Troubles” (see chapter 5). More important, as we will see, movements, parties, and institutions intersect in conflicts leading to war, during wartime, and in war’s wake.

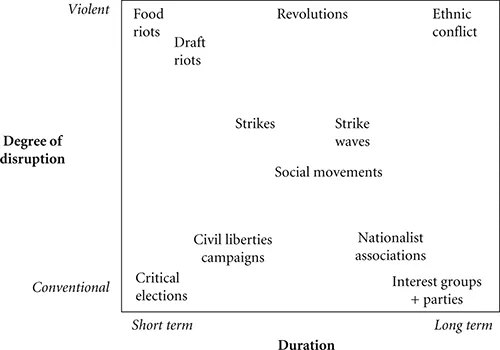

Contentious actors sometimes use conventional means—such as the filibuster in the U.S. Senate—but more often their tactics are transgressive, employing combinations of conventional, disruptive, and violent forms of action on behalf of new or evolving social actors (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001, chap. 2). At one end of this vast spectrum of contention are forms of action that engage contenders regularly with authorities, such as public interest groups and lobbies, whereas at the opposite extreme—and conceptually overlapping with war—are violent forms such as terrorism, revolutions, and civil wars. Figure 1.1 lays out a scheme of the forms of contention we will encounter in this study and their proximity to the boundaries of two key dimensions of contention: its typical duration and its degree of conventionality or violence.

Figure 1.1 is not intended to exhaustively catalog all forms of contentious action but, instead, to help us to think about the relationships among the concepts in the book. First, it ranges from very brief forms (e.g., the draft riots during the U.S. Civil War) to long-term forms (e.g., the Italian Nationalist Associations that preceded and helped to trigger the country’s intervention in World War One); second, it ranges from largely peaceful forms (e.g., elections) to the most violent forms (e.g., revolutions, civil wars, and terrorism); third, movements are more likely to be conventional or disruptive than violent, although they can become violent when engaged with countermovements or the forces of order; and fourth, whereas some of these forms (e.g., elections and riots) have definite organizational formats, others can last for decades with a variety of formats.

Finally, the forms of contentious action we will see in this study are not mutually exclusive. An antiwar movement can produce riots, protest campaigns, petitions, or peace lobbies; social movements can empower a revolution but also engage in legal mobilization; and revolutions, civil wars, and terrorism are frequently commingled. For example. movements sometimes encompass shorter-term strikes and protests, but they often endure for decades and become deeply embedded in state-society relations. Movements often intersect with parties—for example, in the “party in the street” that opposed the Iraq War (Heaney and Rojas 2015). In at least two of the cases we will examine—the French Revolution and fascist Italy—movements became movement-states, which are more likely to go war than are most others.

Will we find a historical progression from lesser forms of contention to greater ones as states grew larger and wars became more deadly? It is logical to think that as wars and the states that fought them expanded so did their forms of domestic contention. But contention over war-making has also become more institutionalized. For example, opposition to the U.S. War on Terror has taken three major forms: an antiwar movement in the street, legal mobilization from human rights lawyers, and the opposition of civil society groups. Moreover, the once-clear lines among forms of armed conflict—interstate wars, extra-state wars, and intrastate wars—have become blurred, and in many countries, the ordinary forms of contention have merged with more violent forms. Technical changes in war-making have, of course, assisted this process, but most important, I will argue, are the processes of globalization and internationalization that have expanded contention across borders since th...