CHAPTER ONE

ADVENTURES IN THE WILDERNESS

William H. H. Murray and the Beginning of Recreational Camping

In the late spring of 1870, with summer rapidly approaching, the editors of the New York Daily Tribune decided to send a reporter into the Adirondack region north and west of the city. Their correspondent had traveled to the area the summer before and with his second arrival was pleased to report that it remained an “Enchanted Ground.” High-altitude lakes and higher mountains made it cool and refreshing during the hot summer months. The paths were quiet, green, and mossy, drawing out hikers onto seven- or eight-mile walks between breakfast and lunch. And everywhere the views were exquisite, varied, and captivating to the eye. If someone chose to camp in this delightful region, the reporter promised, he would “take back with him at the Summer’s close the happiest, brightest, freshest memories of his life.”1

A newspaper report that praises the qualities of a natural place is unremarkable today, but it would have been unknown only a few years prior to 1870. Even the correspondent admitted that the area of mountains and lakes had recently seemed far-off and marginal, with news accounts of it sounding “like legends from a distant and mythical country.” But now, he reported, “this wild region is much more definitely known” and growing rapidly in popularity. This change to the region’s status had come about primarily because an unlikely author, William H. H. Murray, the pastor of Boston’s “Brimstone Corner,” better known as the Park Street Church, had published a groundbreaking book, Adventures in the Wilderness, in April 1869. “Last summer,” continued the reporter, “Mr. Murray’s book, with its fresh, vigorous descriptions … alive with his own intense vitality … and with a sportsman’s love of adventure—drew a throng of pleasure-seekers into the lake region. It was amusing to see the omnipresence of this book. It seemed to be everywhere. Hawked through the cars; placarded in the steamers; for sale in the most unlooked-for places; by every carpet-bag and bundle lay a tourist’s edition of Murray.”2 With the publication of this book, American camping had begun.

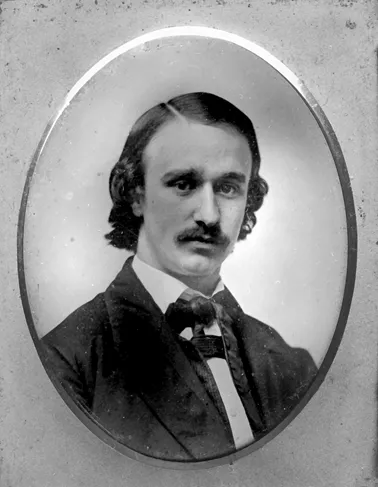

Figure 1.1. William H. H. Murray, circa 1872. Courtesy of the Adirondack Museum, Blue Mountain Lake, NY.

William Henry Harrison Murray

William Henry Harrison Murray came from a modest New England family whose ancestors had been among the first to settle his hometown of Guilford, Connecticut. The fourth child in a family of three girls and two boys, Murray was born on April 26, 1840, in Guilford, to Sally and Dickinson Murray. His mother, who had been a public school teacher before her marriage, possessed a sharp mind and a tendency toward seriousness, and like the other members of her family, she was religious. In her case, religious fervor sometimes prompted ecstatic visions. Murray’s father, a hardworking ship carpenter, was energetic, buoyant, talkative, and engaging but rather improvident. The son would inherit many of his parents’ qualities.3

Murray’s boyhood was an enthusiastic mixture of study, farmwork, and outdoor recreation, leavened by the occasional prank. On one occasion, he tossed a small charge of gunpowder into his school’s potbellied stove, while on another he ignited a newspaper held by his sister Sarah’s beau, apparently thinking the young man’s attentions were proceeding at too leisurely a pace. Young “Bill” came to love the outdoors, learning to shoot, hunt, and fish in the forest and meadows that lay near his family’s home. During these same years, he developed a voracious reading habit, a taste for Latin and literature, and a desire to enter college. It may have been at about this time that Murray had his initial exposure to romanticism. One of Murray’s biographers, Harry V. Radford, related that Fitz-Greene Halleck, a renowned American poet and member of the Knickerbocker Group, “was a fellow townsman of Murray’s, and though much his senior in years, they were intimate friends, mutual admirers, and frequent visitors at each other’s homes. It is said that Halleck taught Murray much of literature and poetry.” It seems likely that Halleck would have introduced Murray to such American romantic authors as Emerson and Thoreau, but he might also have acquainted Murray with the English romantic John Ruskin. Halleck may also have been the source for Murray’s desire to learn, because according to the younger man, his educational ambition was not his parents’ doing. “I had no help, no encouragement. My father opposed me in my efforts, and my mother said nothing.” Nonetheless, they must have felt their son had potential, because Dickinson did not stop Sally from sending Bill to the Guilford Institute, a private Yale preparatory school, soon after it opened. The family, however, had few resources, so young Murray worked on neighbors’ farms to pay his tuition. Nor was he discouraged by the four miles he had to walk each way to the institute or by his need to carry his shoes in order to economize. Instead he leapt into his education, becoming a school leader, a member of the debating society, and the organizer of squirrel-hunting excursions into nearby woods.4

The fall of 1858 found Murray entering Yale College with not quite five dollars in his pocket and all his belongings—a few books and clothes—squeezed into two small carpetbags. Tuition continued to be a challenge for Murray and his family, so he contributed by selling bread, butter, and other goods baked and prepared by his mother and sisters. In addition, he continued to labor on Guilford farms, especially during summer breaks. As earlier in life, Murray was a devoted student in college, but he quickly turned his prankish nature against a distasteful Yale tradition—hazing the freshman. Murray had entered Yale with the largest freshman class in its history. Recognizing an opportunity, and with the college president’s approval, Murray organized his fellow freshmen to frighten away the sophomores, who were seriously outnumbered. The next year Murray continued with his iconoclastic ways by persuading his classmates not to haze the entering freshman. It would not be the last time that Murray demonstrated his lack of patience with traditions he thought outmoded.

Upon graduating from Yale in 1862, Murray, strong, energetic, and good looking (fig. 1.1), married Isadora Hull, an East River, Connecticut, woman who shared his love of the outdoors. Bright and thoughtful, Isadora assisted Murray with his studies after he entered the Congregationalist East Windsor Hill Theological Seminary (now the Hartford Seminary) in East Windsor, Connecticut, and she supplemented the family’s income by teaching school when Murray apprenticed as a pastor’s assistant in New York City. Once he had finished his theological studies, Murray served in a succession of increasingly prosperous and prestigious churches in Connecticut and Massachusetts between 1864 and 1878, most famously at the Park Street Church in Boston. During these years, Murray developed a reputation as a church leader, a public defender of temperance, and an eloquent, engaging speaker. His eulogy of President Lincoln so moved his friends that they had it published. At the same time, however, Murray became notorious for his outdoor sporting activities, which were met with resistance at each of his new churches. The members of his Washington, Connecticut, church were reportedly shocked when Murray once arrived late to an evening service still carrying his game bag and dressed in hunting clothes. He apparently had forgotten about the service and, rushing back to church, had no time to change. Although he explained his tardiness and apologized, his parishioners were not amused. Opposed to a leisure ethic and of two minds about wild nature, Puritanical New Englanders had long rejected field sports as an unseemly recreation for any proper person and felt them especially unsuited for a minister.5 But unlike his peers, Murray would not be contained.

Adventures in the Wilderness

It is unclear how Murray came to visit New York State’s Adirondack Mountains, but he took his first summer vacation there in 1864 and then returned annually for the next fourteen years. He canoed and hiked widely, exploring some of the region’s wildest and remotest corners, but his favorite campsite was small Osprey Island on Raquette Lake across from Woods Point, near the mouth of the Marion River. Occasionally he brought parties with him, which could number as large as thirty, and among them would be not only his friends but his wife and his friends’ wives. “He had a strange notion (or is it so strange?) that women were as strong or stronger than men,” wrote Murray’s daughter about forty years after his death. Custom dictated that middle-class women should stay at their homes, but an iconoclastic Murray felt that they could benefit from wilderness as much as men. Moreover, he “reasoned that the Indian women were able to stand hardships, so why not white women.”6

Smitten by the Adirondacks’ beauty and the outdoor recreations he had enjoyed there with Isadora and their friends, Murray chose to make them the subjects of a series of what he termed “vivacious” essays composed during the mid-1860s. He neither intended them for publication nor even to share with friends, but as a writing exercise to make himself “more perfect in English composition, and … to keep my mind buoyant and out of conventional ruts of expression.” At the time, Murray was the new pastor of the Congregational church in Meriden, Connecticut, which had a “large and intelligent” congregation. Feeling somewhat insecure about his ability to meet their expectations, Murray began to practice his writing each day. Over time he produced “a collection of original [essays] that were unique, and being rewritten time and again, were … as perfect as I could make them.” However, since Murray had no plan to publish them, they would never have seen daylight if not for an accident. Luther G. Riggs, the owner-editor of the Meriden Literary Recorder and a friend of Murray’s, burst into the minister’s office one morning “in a state of mind not easily appreciated save by some country editor in like circumstances.” Riggs had to go to press in four hours, and three empty columns remained to be filled. “You must give me something, Parson,” he begged in desperation. “A section of an old sermon, a portion of a Sunday school address, a bit of temperance talk, a report of a Sunday school convention which was never held—something you have never used—any worthless stuff to fill up the space.” Laughing at his comrade’s consternation, Murray replied, “I have the very thing you want.” Tossing Riggs a copy of “Crossing the Carry,” one of his practice essays on the Adirondacks, Murray assured the editor that “I have never used it and never shall. You are welcome to it.” Riggs hastily printed it on August 14, 1867, and then five more of Murray’s Adirondack essays before the end of October. These sometimes humorous, sometimes serious adventure stories received only a subdued and local response. To Murray’s mind, his Adirondack essays now had reached the largest audience they would, but he was wrong.7

In early 1869, shortly after Murray had become pastor of Boston’s prestigious Park Street Church, a visiting college friend, Josephus Cook, paid him a visit. Cook would become a well-known public orator within a few years, but at the time he was struggling to begin his career. Viewed suspiciously by Boston’s orthodox Congregationalists, Cook was unable to obtain an invitation to speak in church. Murray, however, thought Cook “the ablest man … since Jonathan Edwards,” so he gave his friend the Park Street Church’s pulpit the following Sunday.8 The congregation’s response to Cook’s sermon was strongly positive, and he was swiftly accepted by the city’s other Congregationalists. A few weeks later and in a state of exuberance, Cook again visited his friend to tell him that his becoming pastor of the Park Street Church was a tremendous accomplishment, but that he would never be able “to look upon Boston as captured” until he had spoken in Music Hall, lectured before the Total Abstinence Society, and published a book with the “aristocratic” house of Fields, Osgood and Company, whose list included Longfellow, Emerson, and Hawthorne. Not wishing to publish anything and with no plans to speak in either setting, Murray good-naturedly dismissed Cook’s proposition. To Murray’s complete surprise, that same afternoon brought first a delegation inviting him to speak some evening at the Music Hall and then another asking him to give the annual address before the Total Abstinence Society! Stunned by the turn of events, Murray was standing at the open door as the second committee departed when he happened to spot clippings from his Adirondack articles in the Meriden Literary Recorder. In that instant, he knew what he would next do.

By his own admission, Murray was “utterly ignorant of the conventional way of procedure in such a matter,” but, standing in the doorway with the clippings, he said to himself, “Why not take them across the street [to Fields, Osgood and Company] and see if they will do anything with them.” A few minutes later Murray was being ushered into the office of James T. Fields, the firm’s director, where he briefly stated who he was and why he had called. Despite the impropriety of Murray’s sudden appearance, Fields remained courteous but discouraging. “I regret to say, Mr. Murray, that our list of publications was closed last week, and it would be against the custom of the house to enlarge it.”9 However, having heard of Murray’s “love of outdoor life” and not wishing to embarrass the minister, Fields asked if he and his wife might be allowed to read the manuscript. Murray agreed, and two days later he received a request to return to the publisher’s office. According to Murray, he never forgot “a single phase of that interview,” and it is best told in his own words.

He received me standing with several chapters of my manuscript lying loosely on the desk before him. “Mr. Murray,” he said, “both Mrs. Fields and myself have read these p...