![]()

1 | Development and Conflict

The founding of new cities and the rebuilding or enlarging of the old have created some of the most exciting chapters in history. In preindustrial societies, communities developed physically, socially, and economically over decades and centuries. In contemporary societies, subject to industrialization and urbanization, the process of urban development is intensified. Individual and group interests tend to be sharply defined, and disagreement between parties can erupt into open community conflict that can be disruptive to the social and economic well-being of a community.

The notion of building a “new town” is as old as recorded history. Biblical kings, Greek philosophers, and Roman emperors built new settlements for religious, commercial, or defensive reasons. Hanseatic princes, Renaissance thinkers, and explorer-kings followed similar paths. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century social philosophers pursued the idea, believing it a way to overcome the dehumanizing urban conditions created by industrialization. More recently, national governments have supported the creation of new towns as a means of achieving national economic and social goals. Emphasis has traditionally been placed on the design of the new community: its physical configuration, social and economic activities, and political organization. Little or no attention has been given to the people living or owning property at the site of the new development. What happens to them and why and how they react as they do is what this book is about.

The broader question we are asking is who controls the development of land? Is it the private property owner or the community? These unsettling questions have increasingly provoked controversy in urban and rural America. Various members of a community have widely divergent attitudes toward the development of land: the recent arrival seeks a residence to satisfy personal and family styles; the owner of developable land is concerned with gaining maximum personal financial benefit from future use of his holdings; the merchant and industrialist seek locations enabling them to maximize profits; established residents wish to preserve the qualities that influenced their decision to live there. And so on.

Particularly since the 1960’s, the many individuals who have a stake in the outcome of land-development plans have been active in expressing their opinions. While it is true that public discussion which results in a consensus for action is vital to the future life of a community, violent disagreement about land development can cause irreparable damage to future relationships among community members. Citizens who strongly oppose a change in zone for a land developer will harbor bitterness against those who support change in the community. And how the publicly elected representatives and appointed officials respond to these cross-pressures affects the future quality of the community.

But the vital question of responsibility for decisions on land control has not been dealt with adequately. While statistics on urban sprawl, wastefulness of resources, and deteriorating quality of life are abundant, decisions on such diverse problems as consumption of land around the edges of the cities, dwindling fuel supplies, and damage to the environment require public action based on an understanding of the forces that create and change cities. During the first half of the history of the United States a largely agrarian nation held to a strong belief in the inviolability of private property rights. With the transition to an urban society, our regulatory and service institutions have had to change their concepts concerning the control of land development.

Conflict over land development is not limited to major urban centers where intense activities foster rapid change. Throughout the nation, whether urban or rural, issues such as zoning, highway location, the building of public facilities like schools, or the placement of utility lines arouse conflict. The small community remote from urban concerns can find itself in the midst of turmoil brought about by purely local issues. Or national policies toward the environment can bring about changes in local activities—for example, by controlling how gravel is extracted or how a local industry disposes of its wastes.

I will discuss here the process of urban development and the issue of land-development responsibility—the who, what, when, where, and how of public goals and policies—and specific aspects of the process. The general discussion is from a perspective that views the various elements of city building as interactive forces. Moving from the general to the specific, I will also consider the development of new communities and the conflicts both there and in older communities that arise when proposals are made for land development.

The Central Issues of Change

Change in a community can be social, economic, political, or physical, in one or a combination of these forms. Events surrounding physical change—which involves modification of the natural or man-made environment—provide a source for examining controversies within communities. Contrasted with social or political change—which deals with behavioral aspects of attitudes, beliefs, and values of individuals and organizations—physical change has a visible expression in the process of urban development.

Changes in the physical shape of communities are occurring in increasingly more dramatic and extensive ways. Some occur in an atmosphere of harmony and general consensus, while others stir bitter controversy. Both reactions can establish patterns that shape the future actions of the community. Changes in physical form are part of the complex process called urban development, which by its nature directly affects the lives and financial resources of many individuals in the community. As the complexities of an urban society increase, so do the comprehensiveness, size, and cost of projects. Negative reaction to development, including organized opposition, can disrupt a community by the way in which it modifies the social relationships of individuals and organizations in a community; the disruption can also accumulate excessive financial costs to the parties who may be expected to benefit from the proposal for change.

Ideas for changing the physical environment of a community are embodied in the statements and presentations of individuals, entrepreneurs, public agencies, or government. The suggestions may arise from sources indigenous to a community or from an outside source. In either case, the proposal can take a variety of forms ranging from a utopian generalization to a highly detailed statement supported by technical and financial analyses. The initiation of an idea is part of the process of urban development and its presentation can at once generate conflict within a community. This particular juncture is critical in the “setting in motion” of a conflict, for beyond this point controversies follow similar patterns—often a path that bears little relation to the beginnings of the idea.

Proposals for physical change provide ample source material for studies of community conflict as precipitated by external events. Studies of urban renewal and of highway plans that were brought to the level of controversy have become common in the professional literature of the behavioral and social sciences. However, these case studies are part of a literature generally lacking an initial framework for investigation in the form of a methodology, thus preventing re-evaluation of future events, or comparability with similar studies.

My specific goals here are: (1) to develop an understanding of the progressive stages in emerging controversy over planning proposals for urban development; and (2) to suggest theories as to the causes of different community reactions to change. The steps, or continuous action, which occur from the time a developer conceives of developing land until a project is under construction, involve the actors in the situation, the relationships between them, and the general social climate in which they exist. In each case we should be aware of (1) the characteristics of the actors involved; (2) the set of relations between the actors; and (3) the actors’ environment or social context. We should clearly understand who and what the individuals or groups are and what they represent, if we are to understand their role in the land-development process. The retired farmer, who owns large landholdings, will certainly view development differently than will the young exurbanite family. Similarly, the relations between them influence responses to development proposals. Would the farmer seeking supplemental retirement income, for instance, be concerned over preservation of environmental values? Finally, the social context of the issue, encompassing community attitudes and values, affects the emergence of controversy over development proposals.

In this volume, consideration of different community reactions to change is centered on: (1) the leadership of the community and the developer; (2) the kind of organization proposing the development; (3) the way the proposal is presented to the community; (4) the response of the local bureaucracy to the proposal; and (5) the influence of state and federal actions on the proposal. My conclusions are drawn from studies of three new-community-development projects in upstate New York: two near Rochester, and one near Syracuse. These studies were conducted over a three-year period by “living” with the projects, by regularly visiting each locale, by interviewing residents and developers, and by attending public meetings. In addition, public and private documents were reviewed in detail.

The new community or new town is one of several possible types of urban development. An attribute of the new community (as a type of urban development) is that the adoption stage is a distinct part of the process occurring in a defined time span. One of the distinguishing characteristics of new communities is the extremely large initial investment for a risky enterprise. Location and strength of market become more important for the large-scale, long-term new-community project than they are for other forms of development. These conditions require a well-formulated proposal for development, visibility of participants to increase public credibility and acceptance, and a strategy for presentation designed to gain support. Recent interest in new communities has been generated in America as a result of federal legislation in Title IV of the 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act (PL 90-448) and Title VII of the 1970 Housing and Urban Development Act (PL 91-609). This “new-town movement,” has a lengthy international history with modern origins in Great Britain and Scandinavia. In America, the Greenbelt towns that originated in the Depression era through federal support in Maryland, Ohio, and Wisconsin are part of this heritage.

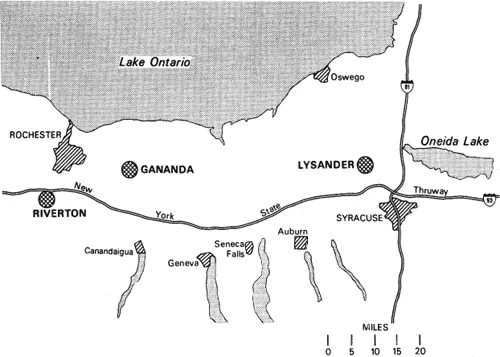

New-community proposals are characterized by the large scale of venture, involvement with multiple departments and agencies at different levels of government, relationships of an existing government to the new populations, and response of indigenous population to the “community builder.” Decisions by the local government can assure success or failure in gaining approval, since support of public services, utilities, zoning, highways, and the tax considerations are vital to the developer. The three new-community proposals we will be discussing (see Figure 1.1) were in early planning stages concurrently in upstate New York in the late 1960’s.

Lysander New Community is located north of Syracuse in the Town of Lysander, Onondaga County, and is the result of a proposal of the New York State Urban Development Corporation (referred to as UDC). This public agency has extraordinary powers under its Act of Incorporation, including complete independence from restrictions of local governments, although here and elsewhere considerable community controversy has centered on resistance to the agency’s proposals. Lysander was the first publicly supported new community to receive federal support, and only one of two publicly supported projects of the fifteen approved through 1973. Gananda is a private new community in Wayne County, east of Rochester and was originally identified with its organizer, Stewart Moot. Land for this venture was purchased privately and lies in a mosaic of towns, villages, school districts, and other governmental units. The project began with local endorsement and a relative absence of controversy. Title VII approval for the privately supported project was authorized in April, 1972. Construction started in the spring of 1973.

Figure 1.1. Map of new communities in upstate New York

The third project, Riverton, is a new community in the Town of Henrietta, Monroe County, south of Rochester. Activities related to the new community have been from private sources with personal identifications. Robert E. Simon (developer of Reston, Virginia, and recognized as instrumental in one of the first postwar United States “new towns”) is publicly identified with the project. Howard E. Samuels and Harper Sibley, prominent local individuals, are also publicized as supporters of the project. In December, 1971, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced that Riverton was the seventh privately supported new-community proposal to be approved under Title VII. All three proposals are in similar stages of development, relatively similar in size, and in close geographic proximity. The social and economic setting of the three proposals are similar. Rochester and Syracuse, seventy-five miles apart, are basically conservative areas. Rochester is a regional center for a population of about 800,000, and Syracuse serves a region of about 650,000. Surrounding areas have highly productive agricultural activities, and each community is the home of nationally recognized manufacturing industries and colleges and u...