![]()

PART ONE

Boys of the Irish Waterfront

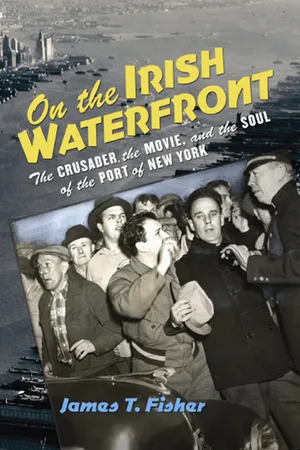

Figure 1. “King Joe and the Boys.” International Longshoremen’s Association life president “King Joe” Ryan is seated next to John J. “Ike” Gannon, president of New York District Council ILA (from Hell’s Kitchen “Pistol Local” 824). Standing are, from left to right, Paul Baker, general vice president; Gus Scannavino, international vice president representing New York; Charles P. Spencer, secretary-treasurer, Atlantic Coast District; Harry B. Hasselgren, international secretary and treasurer, New York; John V. Silke, vice president, Portland, Me. New York City, ca. 1950. Courtesy of the Archives of the Xavier Institute of Industrial Relations, Fordham University Library, Bronx, New York.

![]()

1 Chelsea’s King Joe

In 1912 a West Side boy named Joe Ryan “went down to the docks”—as he ritually testified in later years—to join his older brother Tom and throngs of Chelsea Irish working the magnificent new piers jutting into the North River. Although Joseph P. Ryan’s career as a working longshoreman lasted less than a year, in 1927 he was elected president of the International Longshoremen’s Association. Sixteen years later Ryan’s title was amended to “life president” (see figure 1). Political cartoonist Thomas Nast died a decade before Joe Ryan went to work on the piers, but the spirit of Nast’s lurid anti-Irish illustrations lived on in the ardent Ryan-bashing featured in the nation’s left-leaning journals of opinion from the 1930s through the early 1950s. Unlike his higher-ups in the Irish waterfront chain of command, Joe was always pleased to supply fresh material to his legion of detractors.

Manhattan’s West Side waterfront spawned smarter, tougher, greedier, and far more violent men than Joseph Patrick Ryan, but none was a truer son of the Irish waterfront than “King Joe.” During his nearly three-decade reign as union kingpin, Tammany stalwart, and notorious “mob associate,” Ryan was variously described in public print as a gangster, a soft touch, and a fascist; maudlin, morose, and full of blarney; a captive, a pratt-boy, and a brawler; a trencherman; an aficionado of silk underwear and bejeweled pinky rings; stubby-fingered, cauliflower-eared, and barrel-chested; a hack, a punk, and a thug; a florid plug-ugly; and a devoted family man and daily communicant at his neighborhood parish, Guardian Angel, the Shrine Church of the Sea.

Mary Shanahan Ryan died giving birth to Joe, her fourth child, in Babylon, Long Island, in 1884. James Ryan, like his wife an immigrant from County Tipperary, remarried, and when he died in 1893 his penniless widow, Bridget, arranged for her stepdaughters to board with her brother while she moved with Joe and Tom to a tiny flat on Eighth Avenue in Chelsea.1

Families in that West Side neighborhood were typically large, Irish, and poor; nearly everyone who could work did, including children. Married women had to adapt to the unpredictable cycles of both childbirth and their husbands’ irregular work on the piers. A woman who grew up in the neighborhood recalled: “We had the Wolfs with eight kids. We had the Lynches with twelve kids…. The Applegates had about fourteen. One day, there was all of us comin’ out of the house, and this man came by, and he thought it was a school.”2

Chelsea’s low-rise dwellings “meant that everybody had access to the street.” The neighborhood featured a richly Irish American cultural and religious life, with ten Catholic parishes located between West Fourteenth and West Thirty-fourth streets. There was a lively Catholic Youth Organization and a Police Athletic League famed for annually providing contenders for the Golden Gloves amateur boxing championships. There was “a James Connolly Club, St. Patrick’s Day organizations, Irish youth gangs, even an Irish-American community newspaper, The Shamrock,” noted Chelsea historian Joe Doyle. Then there were the workingmen’s bars: “McManus’s, McIntyre’s, the Bank of Ireland, Moran’s, Shannon’s, Wilson’s, just to name a few.” Life was hard, and “much of the misery was caused by the drinking,” declared a longtime Chelsea resident, recalling these “liquor joints where a stiff shot of rye or gin could be had for a nickel.”3

The ubiquity of alcoholism in Chelsea and neighboring Irish waterfront communities can scarcely be overstated: extreme forms of inwardness, silence, and familial secrecy prompted by alcoholism may even help account for the tendency of the waterfront Irish to offer less than forthright public testimony of their experience with violence and family chaos. In You Must Remember This, a 1989 oral history of Manhattan neighborhoods, the only Irish American Chelsea interviewee willing to treat the issue chose to be identified by a pseudonym. “Peggy Dolan” recalled: “Come Friday nights, the men would come home and get drunk….[T]hey all got drunk. And the women would say, ‘that bum, that bum, here he comes again…. But if you said he was a bum, well, his family would kill you.” An Italian American Chelsea native was haunted for life by memories of “lovely, lovely mothers with black eyes and their kids crying.”4

The World the “Shape” Made

If West Side men hoped to work on the piers, they needed to congregate near if not in the bars, an integral component of the waterfront economy. “When a ship was coming in and reached Quarantine,” recalled an early longshoremen’s union leader,

a flag would be flown from its pier so a gang of longshoremen could be assembled in two or three hours before the ship docked. A hundred men looking for work would leave the saloons and gather on a corner like Twenty-fifth Street and Eleventh Avenue, and the foreman would come over to select the best specimens of manhood from the gangs and assign them to their respective hatches or holes.5

The notorious shapeup endured into the early twentieth century as the dominant mode for hiring longshoremen in most waterfront labor markets around the globe. “The Australians called it the pickup,” according to economic historian Marc Levinson. “The British had a more descriptive name: the scramble. In most places, the process involved begging, flattery, and kickbacks to get a day’s work.” On Red Hook’s Columbia Street a thousand men often vied for one hundred jobs. “It was very bad,” recalled a Brooklyn Italian American longshoreman. “They harassed men[,] …they beat them with sticks.” In Hoboken the hiring foremen “sometimes used fire hoses to protect themselves from the crush of the men.”6

In the Port of New York and New Jersey the “shape” also performed a kind of ritual reenactment of the local social order: it was grounded in forms of authority, benevolence, and deference that were exchanged face-to-face and left obligations undisguised. Everyone knew that a longshoreman sporting a toothpick behind his ear was in debt to a loan shark or bookmaker who worked in partnership with the hiring boss. The shapeup also ritually marked waterfront work as “casual labor,” a bane of reformers but integral to a local political economy geared to rapidly shifting cycles of industrial activity and blessed with a mutually rewarding system of patronage obliging workers to ward bosses and Catholic clergymen alike.

In the decades prior to the Second World War the shapeup was a system built on both exploitation and shared notions of how the larger world worked. Deference and self-sacrifice, as well as the seemingly inviolable code of silence, all figured prominently on the Irish waterfront. In Chelsea, where there emerged a self-styled Irish pier aristocracy of men accustomed to working as members of steady gangs, the shapeup still merited a peculiar respect. Although it was never the sole hiring system in New York Harbor, waterfront insiders and outside reformers alike invested deeply in it as the foundation for their conflicting views of waterfront politics, social life, and religion. Joe Ryan’s fate was yoked to the “shape”: he lent the practice mythic significance even as he denied its centrality in waterfront hiring.7

A Chelsea lifer and a pure product of the world the shapeup made, Joe Ryan attended the parochial school operated by the Jesuit parish of St. Francis Xavier on West Sixteenth Street; he managed to remain there through sixth grade (some sources indicate he made it as far as the eighth) by working as the school’s office boy. Later, following stints as a stock boy and blanket salesman, young Joe caught on as a conductor with the Metropolitan Street Railway. According to the ILA’s official historian, Ryan “was a hard worker whose affable Irish charm won him four promotions; in 1908 Joe was able to marry Margaret Frances Connors, a girl from his own neighborhood.” The year 1912 found him on the Chelsea Piers, where the pay was better but the work more dangerous: just months into his longshoreman career a mistake by a co-worker resulted in a shower of lead ingots raining down on Joe as he stood in a steel tank. “I was hit in the left shoulder,” he later wrote in an unpublished memoir, “fracturing the tip of the clavicle.” Ryan’s colleagues in Chelsea ILA Local 791 came to his aid by electing him financial secretary; parlaying the role into a full-time position, Joe “never did another lick of work on the docks.”8

The ILA originated in the late 1870s in the Great Lakes region, where a Chicagoan named Dan Keefe organized tugboat workers and lumber handlers into a union; it was finally christened the International Longshoremen’s Association in 1895 to acknowledge its Canadian contingent. The Port of New York Local 791, established in 1908, was the self-designated “Mother Local,” a fitting title for an outfit at the epicenter of the Irish waterfront. With meeting rooms eventually located just east of Pier 60 at Eleventh Avenue and West Twenty-second Street, Local 791 was the first ILA branch “to survive beyond infancy” in the port.9

In the second decade of the twentieth century, with one-third of the nation’s dockworkers now located in the Port of New York, the ILA’s center of gravity shifted eastward. The expanding union met resistance in New York from vestiges of the Longshoremen’s Union Protective Association (LUPA), a largely dormant operation revived by Dick Butler, a “fabulous West Side character” and Tammany operative. A brawler and gifted street politician, Butler won an insurgent bid for a seat in the New York State Assembly, then opened a saloon on Tenth Avenue and became a labor leader, finding that “a union was a convenient base for making political deals and getting out—and protecting—the vote during roughhouse Tammany primaries.” The breezily jovial tone of Butler’s mayhem-laden 1933 memoir is highly characteristic of a genre too often imitated by sentimental latter-day apologists for Irish machine politics, whose stylized accounts of “the boys” at work and play are no match for Butler’s firsthand depiction of waterfront brutality.10

Dick Butler bequeathed his model of union leadership to Joe Ryan, whom Butler took under his wing in 1913 after he and Franco Paolo Antonio Vaccarelli, notorious founder (under the nom de guerre Paul Kelly) of the Five Points Gang, merged their LUPA forces with the ILA to create the Atlantic District, with Butler as its first president. His title notwithstanding, Butler was strictly a local character; he handled all negotiations by “going down and having a heart to heart” with employers, a method his protégé Joe Ryan readily embraced. The modern New York-centric ILA emerged from factional struggles in the port during this period, when the union’s “international” president T. V. O’Connor came under fire from Butler and others because as a product of Buffalo and the Great Lakes region, “he didn’t speak our language.” Joe Ryan spoke the language. As Dick Butler wryly predicted in his 1933 memoir, “If he hasn’t forgotten the tricks I taught him he ought to get along.”11

King Joe in the Neighborhood

“From the start, affable Joe Ryan showed skill in labor politics,” wrote journalist Matthew Josephson in 1946. “He possessed a facility with the English language,” gangland historian T. J. English noted; “his red-meat rhetoric was frequently humorous and sentimental.” Ryan’s rapid ascent was also closely tied to location. The ILA’s headquarters was moved to West Fourteenth Street in Chelsea early in his union career. Ryan always treated it as his local clubhouse, even after he rose to the presidency of the union in 1927, with responsibility—on paper at least—for leadership of ILA district operations along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts, across the Great Lakes, and in Canada and Puerto Rico. Locally, according to William J. Keating, “the union was a political auxiliary of Tammany.” Ryan’s ILA powerbase was an integral component of Tammany’s operation in the neighborhood and the city; his chairmanship of the AFL’s Central Trades and Labor Council between 1928 and 1938 strengthened his ties to such citywide political powers as Jimmy Walker, the dapper mayor whose career ended in colorful scandal in 1932.12

The first mayor from the Irish waterfront, James J. Walker grew up on St. Luke’s Place just three blocks from the West Village piers. Like Ryan, he was a product of St. Francis Xavier School. In the late 1890s his father, William H. Walker, Tammany’s commissioner of public buildings, condemned a historic cemetery belonging to Trinity Episcopal Church; it was replaced by a neighborhood park. The Kilkenny-born alderman tended his own interests while serving constituents: the new park, whose presence raised local property values, was located directly across the street from the Walker family home. The Episcopalians retained a young Anglo-American attorney, Samuel Seabury, who with his father, a prominent Episcopal theologian and pastor, helped disinter the remains of Protestant forebears so that Irish Catholic children might play on the site. As a Progressive reformer, Judge Samuel Seabury would later zealously lead the investigation into municipal corruption that brought down the mayoral regime of “Beau James” Walker, privileged son of the Irish waterfront.13

The Seabury family fled their Chelsea home in 1900, part of the Protestant exodus that enabled the Irish waterfront to thrive on the site. Everything Joe Ryan ever needed could be found in the neighborhood: his comfortable home at 433 West Twenty-first Street; the Mother Local at 164 Eleventh Avenue; the Joseph P. Ryan Association clubhouse on West Eighteenth Street, a “private social club” founded in 1923 that “wields much political influence,” as Matthew Josephson reported two decades later. The Tammany Tough Club at 243 West Fourteenth Street was a favored watering hole of a thriving and thirsty local political leadership during the era of Prohibition.14

Above all Joe Ryan had the Chelsea Piers—a cash nexus to ensure that his taste for Sulka undershorts would never strain the family budget—and his church, Guardian Angel, where he was a “bountiful trustee.” Guardian Angel was located just steps from Ryan’s home, replacing an earlier and much less elegant incarnation slightly nearer the Chelsea piers. The façades of the new Romanesque church, designed by John V. Van Pelt and opened in 1930, “were among the most exquisitely crafted of the period”; they “conjured up the image of a humble Lombard country church decorated piecemeal over time.” Few rank-and-file longshoremen worshipped at Guardian Angel, which became known as the “stevedore’s [that is, the employer’s] parish.” Joe and Maggie Ryan were daily communicants at Guardian Angel’s 8 A.M. Mass and often returned in the afternoon to make the Stations of the Cross, a meditative devotional practice once an integral feature of Catholic life.15

Father (later Monsignor) John J. O’Donnell, who became Ryan’s pastor in 1934, reveled in his warm alliance with the labor boss and Tammany chieftain. By the time O’Donnell assumed the pastorate of Guardian Angel, the archdiocese had long since vanquished “any major rivals within the New York Irish community; and the dominant form of politics, that associated with the Democratic Party machine, complemented, rather than contested, the influence of the church.” The loyalty of...