1

CONSUMING WITH A CONSCIENCE

The Free Produce Movement in Early America

MICHELLE CRAIG McDONALD

IN 1838, the Anti-Slavery Society of Newcastle, England, issued a clarion call to United States cotton growers. In a pamphlet tellingly entitled Conscience versus Cotton, it argued that the surest route to abolition was “a wide-spreading and thoughtful conviction, that the unnecessary purchase of one iota of slave labour produce, involved the purchaser in the guilt of the Slaveholder.” This was not to suggest that slaveholders escaped accountability. Indeed, Newcastle’s authors reserved “well-merited scorn and indignant execration” for enslavers’ actions. But it does imply that abolitionists recognized such castigations fell largely on deaf ears. While a few planters saw the error of their ways and recanted—some even becoming powerful symbols for antislavery activism—the majority remained committed to their chosen form of labour. As debates over abolition intensified, proponents changed direction, shifting from production to consumption and asking “every righteous man and every modest woman” to consider, “what can I do to put down slavery?”1

Most scholars, except the few who highlight Revolutionary-era boycotts like those on tea, consider consumer politics to be a modern phenomenon, but such activism was the principal tactic of the free produce movement that emerged on both sides of the Atlantic during the early nineteenth century.2 An effort initially dominated by Quaker and free black abolitionists, the free produce movement encouraged consumers to avoid slave-made goods—like Caribbean tropical commodities and American cotton—in favour of those harvested or manufactured by free workers. Historians have considered both the moral and economic motivations for abolition, but less often how they were intertwined. Such issues were inseparable for the free produce advocates who emerged in the United States in the 1820s and consciously modelled themselves after British antislavery sugar boycotters of the 1790s. These men and women believed that foregoing slave-made goods was only the first step in combating the institution of chattel bondage; offering a free labour alternative was essential to ensuring slavery’s downfall. Fortunately, for those British buyers who wished to buy according to their conscience, help was readily at hand. “Already under the guarantee of the Philadelphia Free Produce Association,” Conscience versus Cotton concluded, “some of this free cotton has been shipped directly to Liverpool.”3

Historians have been less impressed with the ease of ethical buying. While the free produce movement blossomed for a short time, it did not become a viable alternative to slave-produced goods in most communities. Some historians have suggested that it failed because finding free labour cotton and sugar substitutes proved too challenging. Production levels for such goods were low compared to slave-grown commodities, and so purveyors had difficulty building a solid market despite rising disposable income in the lower and middle classes that resulted in what consumer scholars now see as a boom in spending. Buyers wanted more goods, these scholars conclude, but not pricier ones—and the market trumped morality.4

But profitability is only one measure of success, even in histories of the economy. The number of stores that specialized in goods produced by free labour and of free produce associations are others, as is the prominence of free labour ideology in both local and national advocacy movements. Free produce wares flourished in some abolitionist communities—particularly Philadelphia, New York, and Wilmington. Association minutes and correspondence, as well as advertising language, help illuminate how free produce vendors reached these markets while promoting a particular set of social ideals. For while American revolutionary tea party rhetoric encouraged colonists to think about their rights, free produce supporters asked consumers to consider the well-being of others, at the same time that it reinforced the value of a dollar. Free produce sought, in other words, not to distance ethics from economic concerns, but to create both profits for purveyors and consumers with a conscience.

In 1826, Quaker Friends in Wilmington, Delaware, drew up the first charter for a formal free-produce organization, and that same year Baltimore Quaker Benjamin Lundy opened a store that sold only goods obtained by labour from free people. In 1827, the movement expanded with the formation of the Pennsylvania Free Produce Society in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania quickly dominated free produce agitation, but over time more than fifty stores opened in eight other states, including Ohio, Indiana, and New York. Meanwhile, parallel movements operated in Britain and were even attempted by abolitionist advocates in the Caribbean. Such efforts not only linked buying behaviour to notions of morality but also helped promote “free” commodity industries in the East Indies and Africa. “We are too dependent upon American slavery for the supply of this important article,” those targeting U.S. southern cotton argued. “The remedy for this dependence is commercial encouragement” of “the free cotton growers of British India, the West Indies, Africa,” or, much closer to home, the newly independent nation of Haiti, as well as “the free cotton growers of the United States themselves.”5

Although the free produce movement was not strictly a sectarian response to slavery, most association members were Quakers. The idea of a boycott of slave produce dated from at least the mid-eighteenth century when it was advocated by John Woolman, Joshua Evans, and others. Not all Quakers, however, cleaved to these ideals. Some, such as Anthony Benezet, tried to ensure that their marketplace matched their moral code, but others, including Thomas Willing and John Reynell, invested a significant proportion of their mercantile efforts in the slave-based economies of the Caribbean.6

What set the consumer activism of the early nineteenth century apart from these earlier individual efforts, however, was its shift from producers or importers, and their ability to personally decide a course of action, to the far broader base, and larger numbers, of consumers. It also emphasized the power of peer pressure over individual choice. The movement quickly became popular among many abolitionist leaders, including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Gerrit Smith, and the Grimke sisters, who were all early supporters, consumers, and even investors in free labour enterprises, particularly during the peak of abolitionist unity in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Smith, for example, served as vice president of the American Free Produce Association for several years, and Angelina Grimke ensured that her 1838 wedding to Theodore Weld featured only free-sugar desserts made by an African American confectioner. Others promoted the project through publications, including the poet John Greenleaf Whittier who edited the Non-Slaveholder, the most important free produce journal of the early nineteenth century, and, for a time, William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the Liberator. Indeed, in the movement’s early years, Garrison provided extensive coverage of, and editorial support for, the free produce movement. Still others took a more material stance. The husband of feminist Quaker Lucretia Mott ran a free produce store in Philadelphia, and David Lee Child, the husband of the famous writer Lydia Marie Child, traveled to France in 1837 to study sugar beet production in the hopes of finding an alternative to Louisiana’s and Cuba’s cane fields. Elias Hicks and Charles Collins, two of New York’s leading Quakers, used free produce profits to finance emigration efforts to Haiti. Emigration proponents hoped that business-minded free blacks resettled in Haiti might, along with newly manumitted slaves, create a free labour alternative that challenged slavery in both the U.S. and the Caribbean. Toward that end, Collins operated a free produce store on New York’s Cherry Street between 1817 and 1843, selling over fifty thousand pounds of coffee provided by Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer to help finance emigrants’ transportation costs.7

Many well-known black abolitionists, including Henry Highland Garnet, William Wells Brown, and Frances Harper, also supported free produce in their writings and on trans-Atlantic lecture tours, and some, including Lydia White and William Whipper, operated free produce establishments as well. Richard Allen, leader of the African American Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States, joined the Free Produce Society in the 1820s, urging other African Americans to do so as well. He also personally contributed to the manufacture of free labour fashion by recruiting free black seamstresses to design dresses and hats to be worn as material manifestations of abolitionist sentiment.8

In 1838, these efforts coalesced in the Requited Labor Convention held in Philadelphia, which Garrison, Mott, and other abolitionist leaders attended and which led to the establishment of a national American Free Produce Association. In their founding charter, the association declared that “as slaves are robbed of the fruits of their toil, all who partake of those fruits are participants in the robbery.” If these words implied that consumers merely enabled a crime whose main perpetrators lay elsewhere, this was not the position of the free produce activists who understood consumers to be, as one activist put it, “the ultimatum of the whole system” of slavery. “It is clear to those who will take the trouble to examine the subject,” according to another proponent,

that the northern merchant who purchases the cotton, sugar and rice of the southern planter … the auctioneer who cries his human wares in the market, and sells those helpless victims of cupidity … yea, even the heartless, murderous slave-trader, are each and all of them, only so many AGENTS, employed by and for the CONSUMER.9

Moreover the growing number of free produce stores, such advocates contended, made this kind of theft all the more gratuitous.10

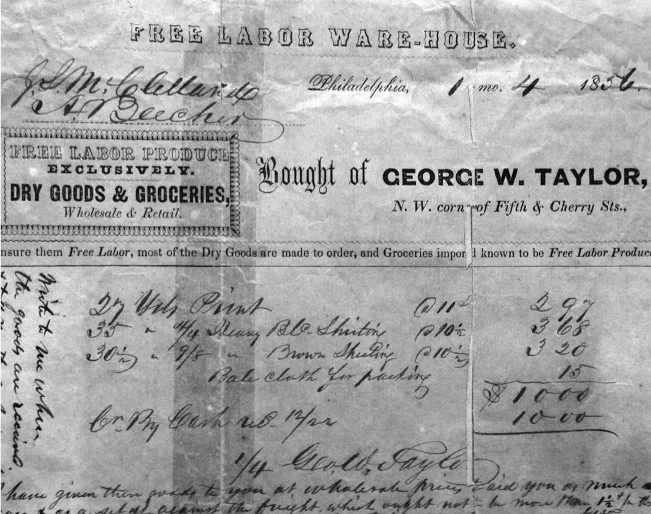

George W. Taylor warehouse receipt, January 4, 1856, property of the author. This invoice from George W. Taylor’s store promoted “FREE LABOR PRODUCE EXCLUSIVELY. Dry Goods and Groceries, Wholesale and Retail.” Made out to J. M. Clelland and A. Beecher, it listed twenty-seven yards print (printed cloth), thirty-five yards heavy black sheeting, thirty yards brown sheeting, and one bale “cloth for packing” for a total of $10.00.

Recognizing the necessary pragmatism of their endeavour and actually building an industry, however, were often two different enterprises. Collin’s New York store, which operated for twenty-six years, was a success by most measures, but other free produce stores operated only briefly, and many were economically unstable. Perkins & Towne, for example, ran a free produce store at 141 Bowery Street in New York City from 1839 to 1841, but Hoag & Wood’s store proved more tenuous. It opened in February 1848 but by October of that year had been taken over by Robert Lind-ley Murray, who, “having purchased the stock of Hoag & Wood, purposes carrying on the business, dealing exclusively in produce which is the result of Free Labor,” at the same location, 377 Pearl Street, New York.11 Murray himself, however, was foundering less than a year later.

Philadelphia’s free produce vendors maintained viable businesses over longer periods of time. James Miller McKim, for instance, began advertising “goods manufactured by the American Free Produce Association,” specifically ginghams, checks, flannels, and muslins for clothing and bed linens, as well as cotton ticking for mattresses, in July of 1848 from his store at 31 North Fifth Street; he continued to regularly run an almost identical notice through 1852. McKim’s mercantile efforts formed only a portion of his abolitionist activities; he lectured extensively, worked with the Underground Railroad, co-founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, and in 1849 was the recipient when slave Henry “Box” Brown was mailed to freedom. He also frequently testified in court on behalf of freed slaves captured under the auspices of the Fugitive Slave Law, which was passed by Congress in 1850 and allowed slave-catchers to seize alleged slaves without due process of law and prohibited anyone from aiding escaped slaves or obstructing their recovery. After the Emancipation Proclamation, he organized efforts to welcome and assist the thousands of newly freed slaves who emigrated north, and in 1865 he co-ordinated the financial backing to establish the progressive magazine the Nation.12

George Washington Taylor had one of the most successful free produce business ventures of all. Taylor had been born in Radnor, Pennsylvania, and attended Quaker schools for most of his education. He was an agent of the Friends Bible Association and publisher of the periodical the Non-Slaveholder and a peace paper written by Elihu Burritt entitled the Citizen of the World. He opened his free produce store on March 4, 1847, at the northwest corner of Fifth and Cherry Streets in Philadelphia, a location which had formerly housed a free produce store operated by Joel Fisher, and he was still advertising from the same location a decade later. Taylor’s advertisements emphasized both the provenance of his producers and the moral culpability of consumers. He specialized in “cotton goods manufactured by the Free Produce Association” and “provided for those who really wish to be non-slaveholders.”13

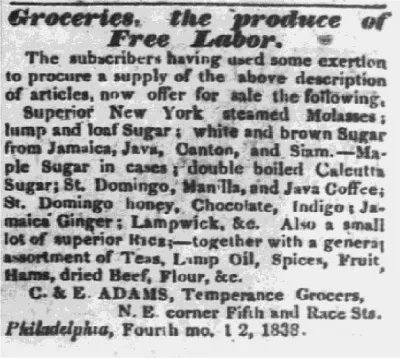

C. & E. Adams advertisement, “Groceries, the produce of Free Labor,” Pennsylvania Freeman, May 3, 1838, Early American Newspapers Series 1 and 2, 1660–1900.

Some free produce stores, to expand markets further still, not only serviced local needs but also operated mail order catalogues, thus expanding the potential reach of their activist impact beyond their neighbourhoods and even cities. Ezra Towne, another New York shopkeeper, assured both “dealers and families” that goods “free from the stain of slavery” were “carefully packed for the country.” McKim advertised his store in both local Philadelphia newspapers as well as Frederick Douglass’ Papers in Rochester, New York, where he noted that “Orders for Goods, or letters describing information may be addressed to J. Miller McKim, 31 North Fifth street; Daniel L. Miller, Tenth street; or to James Mott, No. 35 Church Alley.”14 Taylor likewise began his free produce store with cotton cloth and bedding, although by 1855 had expanded to include “an assortment of groceries,” and two years later offered “prices, lists, and samples sent by mail.”15

Storekeepers who opted to limit supply sources to thos...