![]()

CHAPTER 1

Boom and Bust

The First Great Depression might be regarded purely as an economic crisis, and in its early phases the economic aspects—the see-sawing of trade, employment, and investment—were certainly the most easily observed. But a great trauma such as this should not be regarded only as an economic phenomenon. Economic woes soon spawned other troubles, and in its later phases the Depression could as easily be viewed as a political, and a cultural, and a diplomatic crisis. Regardless of how the Depression is perceived, though, there is a common theme: the pervasive influence in American affairs by the superpower, Great Britain. For this reason it is probably fitting that one of the most eloquent observers of American woes was an Englishman, Charles Dickens. The nation which he described during his 1842 visit was one whose economy was deeply integrated with, and heavily dependent on, that of Britain.

While many Americans believed that the spectacular boom of 1835–1836 and the extraordinary collapse of 1837–1839 were primarily the result of decisions taken by businessmen and politicians in the commercial and political centers of the United States—and indeed, were encouraged to believe this by many in the country’s political class—the truth was more complicated. In reality, national prosperity hinged heavily on the actions of institutions and businessmen on the other side of the Atlantic, who were far removed from the tempest of American politics.

Hard Times

Let’s all be unhappy together.

—Motto of the World’s Convention of Reformers, New York City, October 1845

In January 1842, Charles Dickens arrived in Boston. He was only thirty years old, but already famous in America as the author of Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, and other works. He was in the United States to give lectures, and besieged by admirers from the moment Cunard’s steamship Britannia docked in Boston harbor. But the mood of the country was not good. “They certainly are not a humorous people, and their temperament always impressed me as being of a dull and gloomy character,” Dickens wrote. “In travelling about out of the large cities, I was quite oppressed by the prevailing seriousness and melancholy air of business.”

Dickens visited Philadelphia, a rival to New York as the nation’s financial center, in early March. He arrived late at night, and while looking out his hotel room window he saw across the street

a handsome building of white marble, which had a mournful, ghost-like aspect, dreary to behold. I attributed this to the sombre influence of the night, and on rising in the morning looked out again, expecting to see its steps and portico thronged with groups of people passing in and out. The door was still tight shut, however; the same cold, cheerless air prevailed…I hastened to inquire its name and purpose, and then my surprise vanished. It was the tomb of many fortunes; the Great Catacomb of investment; the memorable United States Bank.

The vast headquarters of the Second Bank of the United States, modeled on the Parthenon and completed in 1824, was built as a temple of finance. President Andrew Jackson tried to kill the bank just eight years later, when he vetoed the renewal of its federal charter, but the Bank refused to die. Its president, Nicholas Biddle, persuaded the legislature of Pennsylvania to give him a state charter, and the bank carried on as the most powerful financial institution in America. It was financial crisis that finished Jackson’s work, when the bank finally collapsed in February 1841.

“The stoppage of this bank, with all its ruinous consequences,” Dickens wrote, “had cast (as I was told on every ride) a gloom on Philadelphia, under the depressing effect of which it yet labored.” On the edge of the city, Dickens saw the unfinished marble structure of Girard College. “The work has stopped,” he said, “like many other great undertakings in America.” The gift that supported the new college had been heavily invested in Bank of the United States stock. (Much of the rest of Girard’s gift was invested in Pennsylvania state bonds, an apparently conservative decision until Pennsylvania itself defaulted in August 1842.) The Girard Bank, also founded by the college’s benefactor and coincidentally based in the old offices of the First Bank of the United States, collapsed after a run by depositors five weeks before Dickens’s arrival.

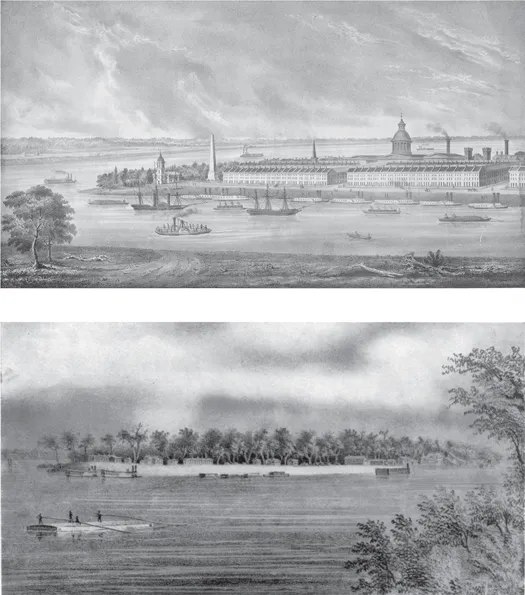

And yet, there were parts of the country in even worse condition. In April, Dickens found himself on a mail boat steaming from Louisville to St. Louis. As the ship steamed from the Ohio into the Mississippi River, Dickens saw on the starboard shore

a spot so much more desolate than any we had yet beheld…. At the junction of the two rivers, on ground so flat and low, and marshy, that at certain seasons of the year it is inundated to the house-tops, lies a breeding-place for fever, ague, and death…. A dismal swamp, on which the half-built houses rot away; cleared here and there for the space of a few yards; and teeming, then, with rank, unwholesome vegetation, in whose baleful shade the wretched wanderers who are tempted hither droop, and die, and lay their bones; the hateful Mississippi circling and eddying before it, and turning off upon its southern course, a slimy monster hideous to behold; a hotbed of disease, an ugly sepulchre, a grave uncheered by any gleam of promise; a place without one quality, in earth or air or water, to commend it.

This was Cairo, Illinois. Only seven years earlier, there had been little here at all. Then an entrepreneur named Darius Holbrook launched a grand plan to build a city, “a great commercial and manufacturing mart and emporium,” at the confluence of the two rivers. In 1836 Holbrook went to London and retained a prominent investment bank, Wright & Company, to borrow large sums for his scheme. British investors, lured by color lithographs showing the factories, churches, domed municipal buildings, and crowded streets of the new metropolis, bought million of dollars in Cairo bonds. Wright & Company went bankrupt in November 1840. Holbrook defaulted too, and so did the state of Illinois itself, just as Dickens was arriving in Boston. Many Britons vowed never to do business in America again. “A mine of Golden Hope,” Dickens called Cairo, “speculated in, on the faith of monstrous representations, to many people’s ruin.”

Americans loved “smart dealing,” Dickens said. But they did not understand how much it had damaged the country’s reputation and prospects, “generating a want of confidence abroad, and discouraging foreign investment.” Nor did he have confidence in the capacity of the country’s leaders to repair the damage. President John Tyler, whom he met in Washington in March, “looked worn and anxious” after only a year in office. “And well he might,” Dickens added, “being at war with everybody.” In the House of Representatives, meanwhile, Dickens saw “the meanest perversion of virtuous Political Machinery that the worst tools ever wrought…in a word, Dishonest Faction in its most depraved and most unblushing form, stared out from every corner of the crowded hall.”

FIGURE 4. Two Views of Cairo, Illinois. Top: Prospective View of the City of Cairo, 1838. Source: Chicago History Museum. Bottom: View of Cairo, Illinois in 1841. Source: Library of Congress.

Dickens left the United States in May 1842. When he had arrived, four months earlier, he was burning to learn more about America. His departure was more subdued. “I don’t like the country,” he confided to his friend John Forster. “I would not live here, on any consideration. I think it impossible, utterly impossible, for any Englishman to live here, and be happy.”

It was not the best of times. The United States enjoyed extraordinary growth until the fall of 1836, but then it was convulsed by a panic in the financial sector in the spring of 1837. It seemed to be on its way to recovery in 1838, but by the end of 1839 the country was sliding into a deep, apparently irreversible depression. Dickens’s view of the United States a little more than two years later was bleak but not unusual.

In Philadelphia, the diarist Sidney George Fisher had at first dismissed fears about an economic collapse. “The Capitalist is the most easily frightened of beings,” Fisher wrote in 1837. “A few speculators & imprudent merchants may fail, but the thunderstorm will soon be over & the atmosphere will be clearer than before.” Fisher himself was a capitalist, the head of one of Philadelphia’s leading merchant families, but he completely misjudged the oncoming storm. In July 1842, Fisher confirmed the dismal prospect of the city that Dickens had offered five months earlier:

No society, no life or movement, no topics or interest of any kind. Everybody has become poor & the calamities of the times have not only broken up the gay establishments & put an end to social intercourse, but seem to have covered the place with a settled gloom. The streets seem deserted, the largest houses are shut up and to rent, there is no business, there is no money, no confidence & little hope, property is sold off every day by the sheriff at a 4th of the estimated value of a few years ago, nobody can pay debts, the miseries of poverty are felt both by rich & poor, everyone you see looks careworn and haggard, and the whole community seems watching with trembling anxieties the movements of a set of selfish and corrupt politicians at Washington & Harrisburg.

New York City was also desolate. On Wall Street, business was “next to nothing,” the United States Democratic Review reported. “Prices have been steadily falling for many months. The transactions, which once were sufficient in New York to give employment to a board of eighty brokers and upward, are now dwindled to very unimportant amounts.” The harbor was quiet as well. “The past season has been one of unusual prostration of business,” reported the Sailor’s Magazine. “The large number of ships lying at our wharves for months unemployed, have borne melancholy testimony of the complete stagnation of trade. Thousands of seamen have been cast on shore with but a few dollars in their pockets, scarce enough to pay a fortnight’s board.”

The novelist Charles F. Briggs, an aspiring Dickens, published his first novel, The Adventures of Harry Franco, in 1839. It was set in New York City in the early months of the crisis, when “a panic seized upon the whole people, such as had never been known before, except when sudden fear has struck upon the hearts of a city, from a convulsion of nature, or the approach to the gates of a hostile army.” His next novel, The Haunted Merchant, was published in 1843. It described the anguish of a New York businessman bankrupted in “those unlucky years when everybody loses money, and a poverty-struck feeling, for some unaccountable cause, pervades the community.” Briggs’s fiction reflected the hard reality. Philip Hone, a former mayor of New York, wrote in his diary in July 1842 about the city’s newly completed federal customs house, another marbled Parthenon whose construction had begun during the boom years eight years before:

It is intended to collect the import revenue upon the commerce of the nation; but how if it should prove that, the commerce being annihilated, there will be no revenue to collect? A splendid reservoir has been prepared, with fountains whose streams are to irrigate the lands in all quarters; but how melancholy would it be to discover that, after all of these preparations, the springs are to be dried up and the waters have ceased to flow. It looks awfully like it just now…. The cage is splendid, but the bird has fled…. There must be a recuperative principle in this great country to restore things some time or another, but I shall not live to see it.

The great pride of New York State was the Erie Canal, a 360-mile-long waterway that connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes and radically reduced the cost of shipping from the Atlantic seaboard to the western states. Completed in 1825, the canal was a technological and economic marvel which encouraged a massive expansion of canal systems across the whole country. In 1836, the New York legislature authorized a debt-financed expansion of the canal that it projected would be entirely repaid by burgeoning toll revenue. Six years later, freight going to western states was down by 40 percent, while eastward traffic was stagnating. The legislature halted canal improvements in March 1842.

The West, as Dickens had seen, was in trouble too. In 1837, Horace Greeley called it the “Great West…the true destination” for newly landed immigrants. But the West was great no longer. In the wake of financial crisis, historian Roy Robbins wrote in 1942, came “desolation, chaos, and ruin.” In Cincinnati, a newspaper reported: “Working men are becoming almost desperate for want of work. There is nothing for them to do—they are actually offering to work for their board along the river streets. This is not exaggeration, it is a melancholy fact. It is rumored that the two steamboats burnt a day or two since, just above the city, were set on fire by men out of employ, so as to get the work to rebuild them.”

James Kirk Paulding, Secretary of the Navy in the cabinet of former President Martin Van Buren, gave a firsthand account of the devastation in the West. Soon after his defeat in the 1840 election, Van Buren decided to rebuild his political fortunes by making a tour of the West. Paulding travelled with him. In June 1842, Van Buren and Paulding parted company in Cincinnati, with Paulding taking the steamboat down the Ohio to the Mississippi and then north to St. Louis. He was following the path Charles Dickens had taken only two months earlier. But Paulding continued north to the mouth of the Illinois River, and then up the Illinois itself toward Chicago. All along the shores, Paulding found people “almost without exception, complaining of hard times.” The market for crops and livestock had collapsed. “All wish to sell and nobody cares to buy,” Paulding wrote.

Signs of decay multiplied as Paulding headed northward. In 1835, the Illinois legislature had approved a plan to connect the head of the Illinois River to Lake Michigan by building a one-hundred-mile canal from Peru to Chicago. The project was financed by state-guaranteed bonds, many sold to British investors. The prospect of a navigable route from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi triggered rampant speculation in land along the route. By 1840, however, the state’s financial condition was so bad that the legislature stopped work on the canal with the last thirty miles to Chicago unfinished. The state’s default in January 1842 made immediate resumption of construction unlikely. The result was a series of ghost towns on the banks of the Illinois. They were “a mere spasmodic effort of speculation,” Pauling said, some marked by a few lonely houses, and others with “nothing but a name and a lithographic map to demonstrate their existence.” Paulding concluded that the people of Illinois “had been precipitated from the summit of hope to the lowest abyss of debt and depression. It was the feverish anxiety, the headlong haste, the insatiable passion for growing rich in a hurry, that brought them and other states where they are now standing shivering on the verge of bankruptcy.”

In Chicago itself, by another account, “the hotels were emptied of guests and the streets deserted. Business had vanished like smoke, leaving 4,000 ambitious resourceful people stranded amid the wreck of their fortunes without any outlet for their energies.”

Eighty miles north of Chicago, the residents of Milwaukee were suffering as well. James Buck had been there for only six years in 1842, but was already one of the longest residents in this infant city. Once a sailor, Buck had just returned to Boston from Calcutta in 1836 when he met an old schoolmate who was striking out for the frontier. The stream of emigration to the western states was “like a tidal wave,” Buck said. Building lots in Milwaukee were already selling “for prices that made those who bought or sold them, feel like a Vanderbilt. Everyone was sure his fortune was made…. Nothing like it was ever seen before; no western city ever had such a birth.” Then came the crash. Buck recalled:

The emigrants were few and far between. A wave of disappointment rolled over the little hamlet, filling the hearts of the people with sadness, blasting all their hopes, and leaving them to live, as best they could, upon their own resources, and to prey upon each other. The wealth that many of them supposed they possessed, took to itself wings and flew away. Lots and lands for which fabulous prices had been paid in ’36, were now of no commercial value whatever. The desideratum was bread and clothing, and the man who could procure these, was lucky.

In 1836, the engine of the American economy had been the cotton plantations of the South. But now “the sad, monotonous complaint of hard, hard times”—as Augusta, Georgia’s Southern Cultivator called it—could be heard across the South as well. A state legislator in Richmond in March 1842 said that

the pecuniary embarrassment that now pervades every portion of the Commonwealth, threatening ruin and disaster to all classes of society, is a fact as notorious as it is deplored…. [I]t presses with accumulated violence and intensity on the south-western portion of Virginia. The intelligence received from every part of that ...