CHAPTER 1

Heresy Hunting Begins in Ireland

The Trial of the Templars and the Case against Philip de Braybrook

According to John de Pembridge, writing in the second quarter of the fourteenth century, a moon of diverse colors shone on December 14, 1312, “in which it was divined that the Order of the Templars should be abolished for all eternity.”1 The evidence of the forty-two outside witnesses in the Irish trial, who offered the only unanimously negative assessment of the order in the British Isles, further indicates support for the order’s suppression, by then a fait accompli.2 Yet the trial passed virtually unnoticed by contemporary Irish or Anglo-Irish annalists. Pembridge himself, a Dominican of St. Saviour’s Priory in Dublin, records their arrest and imprisonment in trans-marine lands, England, and Ireland but says nothing about their subsequent fate apart from the marvelous moon and its implications.3 Only “Chronicler A” of the “Kilkenny Chronicle” noted their trial in Ireland or elsewhere.4 Friar John Clyn, who also composed his annals in the second quarter of the fourteenth century, mentions merely that the order was dissolved by the Council of Vienne in 1312.5 The mid-fourteenth-century scribe of the Annals of Inisfallen discusses the council in relation to the refusal of several Irish bishops to attend “for fear that unpleasantness might befall them.” He also fulminates against the Spiritual Franciscans who, “spreading the poison of their diabolical tricks under the semblance of religion and false piety, have wickedly submitted themselves, their sect, and their erroneous doctrine to the immediate protection of the Holy See and of certain people of the Curia who support them.” Franciscan representatives, he tells us, requested of the pope and council that they condemn Spiritual Franciscan teachings, “lest from the deadly draught the Lord’s flock contract the disease of heretical leprosy.”6 On the matter of the Templars, about whom similar remarks could have been made, the scribe is silent, as indeed are medieval Irish or Anglo-Irish annalists regarding Templars in general.7

Thus Ireland’s first full-fledged heretical inquest seems to have aroused little interest among either colonists or the native Irish, at least in the records. This apparent apathy becomes all the more perplexing in light of the position of power and privilege Templars enjoyed in the lordship, as they did throughout Britain and western Europe prior to their precipitous fall from grace, and in light of the damaging testimony given by Templars themselves during their examination in Ireland, which has led one scholar to conclude that they were tortured.8 Nor has the trial in Ireland garnered much interest among modern scholars, apart from Helen Nicholson’s studies of the trial in the British Isles. It inspired one of its inquisitors, Thomas de Chaddesworth, however, to immediately adopt similar techniques against an old rival, Philip de Braybrook. The case against Braybrook was apparently tried in the same place (St. Patrick’s), by the same man (Chaddesworth), and in the same year (1310) as the trial of the Templars. It illuminates the dynamics between Dublin’s dueling cathedral chapters, St. Patrick’s (represented by Chaddesworth) and Holy Trinity (Braybrook), and the ways in which accusations of heresy were promptly seized upon in medieval vendettas, yet it has been largely ignored by scholars. Both cases, and especially that of the Templars, set a standard that would be followed in the coming decades: trumped-up charges to discredit opponents without solid supporting evidence. As Chaddesworth copied the tactics used against the Templars in his own feud with Philip, so would colonists copy Ledrede’s tactics in theirs with the native Irish.

Ireland had never witnessed anything like the Templar trial, but over the next fifty years it experienced a rash of heresy accusations and trials, more than in the rest of the Middle Ages combined. While the trial of the Templars in Ireland directly influenced only the case of Philip de Braybrook, their trial in France most likely shaped the perspective of the man responsible for most of Ireland’s future trials and accusations, Richard de Ledrede, and it provided a context for participants in Ledrede’s and other subsequent proceedings in Ireland. Moreover, the trial provides invaluable insight into the colony’s initial response to and understanding of heresy, as well as into the development of that response and understanding throughout the following half century. The trial of the Templars in Ireland also enables exploration of the order and the accusations against them in a land in which they were almost entirely separate from their original purpose, the recovery of the Holy Land. The loss of that purpose after the fall of Acre was a primary cause of their demise, yet this dimension seems to have held little significance for those in Ireland, which was more of an object than an agent in the crusading movement.

Templar History in Ireland Prior to the Trial

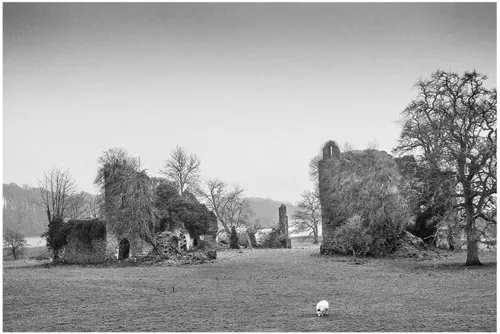

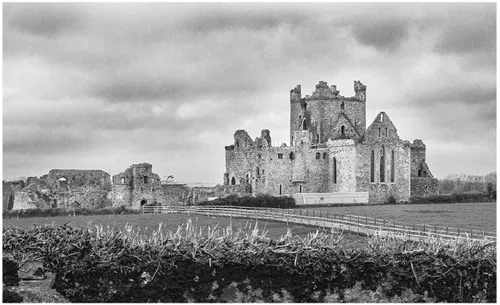

The Knights Templar came to Ireland with the Anglo-Normans, possibly accompanying Henry II, who pledged to support Templars as part of his penance for the murder of the archbishop of Canterbury—a penance intertwined with his very conquest of Ireland.9 His grant to them of lands in Ireland was confirmed by every king of England up to Edward II, who perhaps did not have time to confirm the grant before the events in France reached his ears.10 Thirteen Templar preceptories have been identified in Ireland, only one of which lay outside colonial territory, and they may have had as many as forty-five other preceptories, houses, and churches.11 The Irish Templars were a branch of the English province, and the preceptor of Ireland, though more often called master of Ireland, was subject to the English master.12 Their experience in Ireland was similar to that of the order in England, particularly preceptories in the countryside, with greater engagement in agrarian activities than in military or political ones. One document attests that native Irish were involved in the order, at least in Clonaul in the early fourteenth century, but it cannot be determined if these were members or tenants.13 Native Irish could have entered as sergeants or chaplains, but it seems unlikely given the usually rigid divide in Ireland between ethnicities in religious houses. All other known Templars in Ireland were almost certainly of English extraction and, judging from the Templars who were tried, most entered the order in England.

The Templars had extensive rights and concessions in Ireland, as elsewhere. The papal privileges lavished on the order were legion: they were under the pope’s direct authority and thus exempt from episcopal jurisdiction; they had their own clergy from whom they could receive the sacraments, but who were subservient, like all members, to the grand master; they did not have to pay tithes but instead could claim them, and alms given to the Templars were said to absolve donors of a seventh of their penances; they could not be placed under interdict or excommunication except by the pope, and if an area was under interdict when the Templars came to make their annual collections, the churches were to be opened, services held, and donations made. The kings of England further augmented these favors. They could not be tried before anyone in Ireland but the justiciar or the king, though after 1210 no king of England visited the island while Templars were still around to enjoy this privilege, and they had their own courts with full jurisdiction over their tenants. They were free from all amercements, aids, tallages, and tolls, as well as military service, an odd exemption for a military order and one the Hospitallers apparently did not share. Such generous grants, however, often proved difficult for the Templars to enforce, at least in England, where they were dependent upon the fickle favor of the king, who could at pleasure allow or withhold many of their privileges, both financial and jurisdictional. They do not seem to have served as bankers nearly to the extent the order did elsewhere, but the preceptors of Ireland often acted as auditors for the Irish treasurer and sometimes served as collectors of both secular and religious monies.14 They also occasionally acted as mediators in important affairs, including for the king.15 By the nature of the colony, the Irish Templars did not have as close a relationship with the king as did their English brethren, yet they were clearly well favored and their leaders high-ranking men.

Evidence for the resentment that played such a critical role in their downfall is slight and indirect in Ireland. They were at times prevented from making annual collections by local clergy who exacted their own collections before Templars could do so.16 Though the colony was often at war with the native Irish and the king frequently enlisted colonists to fight in his wars elsewhere, the Irish Templars do not seem to have participated in such military activities, although Irish Hospitallers did, as did English Templars in Edward I’s campaign against Scotland.17 Rather, when Irish Templars were assessed to supply soldiers and horses, they proved themselves exempt. One such occasion was in 1302, when the sheriff of Dublin seized and sold the Irish master’s livestock to exact a fine levied on him by the Irish exchequer for failing to provide horses and men at arms to maintain peace in the land. The court awarded the master damages for the seizure and mistreatment of his property, since “he and his predecessors were always and ought to be free and quit of the finding of such horses and men, by charters of the Kings of England.”18 As Templars could be tried only before the justiciar or the king, they often successfully stalled suits made against them, as in the dispute over lands with the abbot of St. Mary of Dunbrody that began in 1278 and took thirteen years to resolve. The abbot complained that the delay had caused his house to fall into poverty and would lead it into ruin if he continued the case “against such powerful opponents as the Templars.”19 In the end his patience and perseverance profited him nothing; the master of Ireland paid him one hundred marks for recognition of Templar ownership of the lands, which did little to recoup the cost of the case for the abbot.20

The financial privileges enjoyed by the Templars, which intensified the burden that fell on others, may have been a source of ill will toward them, but it also made them attractive lords. Repeated references demonstrate that colonists were more likely to establish connections with or copy them than to clamor against them.21 Templars shared with Hospitallers virtually every secular privilege they enjoyed in Ireland, the exemption from military service a notable exception, and all royal mandates that attempted to limit their role as landlords were directed at the Hospitallers along with the Templars. Thus it seems unlikely that Templars aroused any particular animosity among the laity or religious, especially since the latter often benefited from similar if less extensive privileges themselves. Even the non-Templar witnesses in the trial offered little against the Irish Templars in particular, though they claimed to have heard or known about a great many crimes committed by Templars elsewhere, including sodomy, murder, and appropriating lands unjustly.

Three troublesome Templars are known from the Irish branch prior to the trial, all of them masters. In 1235, Henry III ordered the justiciar of Ireland to arrest Ralph de Southwark, who had been master of Ireland bu...