U.S. Mortgage Market Development and Federal Policy to the Early 1990s

To understand how the mortgage market problems of the 1990s and 2000s developed, and how fundamentally different these markets functioned compared to earlier periods, it is helpful to look much further back to the evolution of home finance in the United States, particularly the origins and institutionalization of loan products such as the long-term, fully amortizing, fixed-rate mortgage that became the dominant home loan of the twentieth century. The development of this product and the generally stable—but far from perfect—mortgage market that accompanied it was hardly a creature of unfettered private market innovation. Rather, it was the outcome of a fundamentally mixed sector of the U.S. economy, which included and required a persistent role for government as an innovator, an investor, and a regulator. During the 1980s and 1990s, however, policymakers began making explicit choices to move toward a highly deregulated system of housing finance. This left an increasingly large portion of the mortgage market subject to little regulation, shifted substantial amounts of risk from lenders to borrowers, and exacerbated boom-bust cycles in housing prices.

Certainly, U.S. mortgage markets had very serious flaws before the 1990s, especially in terms of continual disparities in access to credit across race and space. However, many of the policy solutions to these problems—especially increased enforcement of fair lending and community reinvestment laws—were just beginning to gain headway in the early to middle 1990s when the first boom in subprime lending came along, largely eviscerating many of the gains made under these policies, which had already been limited by flaws in design and inconsistent enforcement. Notwithstanding strong, repeated signs that deregulation was resulting in serious problems of mortgage abuse, increases in market risk and foreclosures, and disparate access and pricing among different segments of the population, bank regulators and policymakers continued to tout the purported benefits of deregulation and “market innovation” with little scrutiny of these supposed benefits or considerations of the costs.

In this chapter I focus on the development of the government-supervised, risk-limited mortgage market, as well as the creeping move over the last quarter of the twentieth century toward deregulation and increasingly unsupervised market innovations, many of which fed directly into the excesses and abuses of the late 1990s and 2000s. The timeline of mortgage market development and change is not one of bright lines and clear boundaries, although there are certainly periods during which change occurred quite rapidly. Rather, different outside forces—including those based in technology, policy, and demography—were occurring, often simultaneously, and were interacting with each other to produce new financial products and practices, changes in the structure of the financial services industry, and various market opportunities—and often vulnerabilities—among homeowners and would-be homeowners in different parts of the country.

Since at least the early 1920s, the federal government has been a supporting—and sometimes catalyzing or initiating—actor in the promotion of homeownership for a broader segment of society. Beginning with various forms of homeownership boosterism and then moving fairly quickly into intervention and innovation in mortgage markets, Congress and the executive branch became key partners in the development, expansion, and direction of homeownership and mortgage finance.

Pre-Hoover Home Finance

Before the 1930s, many Americans, even many with decent incomes, found it quite challenging to borrow sufficient funds to purchase a home. The homeownership rate at the turn of the century was just above 46 percent and, despite the very large economic expansion of the 1920s, it had climbed to only just under 48 percent by 1930.1 When compared to the homeownership rate of some other countries, including the United Kingdom, this rate was not particularly low, but this was partly attributable to the relatively rural nature of the United States at the time (homeownership rates in cities tended to be lower than in rural areas) and to the desire of recent immigrants in the United States to own their own home (Harris and Hamnett 1987). Moreover, up until 1940 the U.S. homeownership rate remained relatively low compared to post–World War II levels.

The structure of homeownership finance certainly played a key role in the relatively limited extent of homeownership before the 1930s. Going further back, to the early nineteenth century, institutional lending for homeownership was relatively rare, and generally dates back to the first terminating building society in 1831 (Fisher 1950; Lea 1996). For the nonaffluent, owner occupancy was usually achieved during this preinstitutional period either through a combination of doing much of one’s own construction, extensive household savings, borrowing from individuals, and land contract financing (Weiss 1989). Land contracts are essentially rent-to-own schemes in which the buyer does not gain ownership of the home until he makes many years of what are essentially rent payments. If payments are missed, the buyer is evicted and has no equity in the property and no right to redeem it in any way. Land contract sales were frequently used by land subdividers, who would sell parcels to families on which they could build their own house, and by developer-builders well into the twentieth century. They were also used to transfer property between individuals as a form of seller financing.

It is no coincidence that institutional lending in the United States and in England developed alongside the Second Industrial Revolution and large-scale urbanization in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century (Mason 2004). Rural homesteaders faced fewer obstacles to home building and ownership than urban households. Land was relatively inexpensive and materials could be harvested off the land for the most part. As cities grew and land values rose, working class and modest-income families could rarely afford to buy land and build a house without some sort of financing over time.

At least through the 1970s, it is arguable that no single type of institutional mortgage lender was more important to the development of government-supervised, risk-limited mortgage markets than the building and loan (B&L), later called the savings and loan (S&L). This is not due solely to the fact that the B&L became a major provider of mortgage credit but also because of its direct and indirect effects on the structure of home finance and the mortgage market itself.

Historians tend to point to the Oxford Provident Building Association, established in 1831 in what is now Philadelphia, as the nation’s first B&L (Hoffman 2001; Lea 1996; Mason 2004). The early B&Ls were actually local “terminating building societies.” Those joining a terminating B&L would make regular payments on shares they purchased in the B&L as a form of savings. Once enough capital was accumulated in the B&L to build or purchase a house, the capital was auctioned off to the member willing to pay the highest interest. The resulting payments by the borrower were then distributed to members as dividends. Once everyone had paid for their loans in full, the organization closed its doors.

By the latter half of the nineteenth century, permanent B&Ls began forming. These institutions allowed shareholders to vary the amounts of their contributions more easily and to vary the timing of share payments and withdrawals. They also began the practice of setting up reserve funds—loan loss reserves—to prepare for potential loan defaults and losses.

The primary purpose of early building and loans was not to earn a profit, at least not directly, but rather to promote homeownership. In many cases, local merchants and businessmen helped organize them in order to stimulate residential and economic development. At the same time, many participants and organizers saw the promotion of savings and loans, and the resulting homeownership, as the development of a movement more than an industry (Lea 1996; Mason 2004). Building and loans were local institutions, with members all living in the same area and many of them knowing each other. This social and geographic cohesiveness gave them an informational advantage that kept underwriting costs and defaults low.

Time deposits—the equivalent of certificates of deposit today—were introduced by B&Ls in the late nineteenth century and were offered at fixed terms. This created greater funding and liquidity in the mortgage system and allowed for more pooling of risk. Borrowers and savers benefited from economies of scale as the organizations grew. Yet, once B&Ls began offering deposit services to nonborrowers, they lost some of their inherent peer-lending enforcement advantages. Depositors and borrowers were decoupled–so that losses from defaulting borrowers were spread over more depositors. By 1931, of the twelve million savings and loan members in twelve thousand institutions, only two million had home loans (Hoffman 2001, 154). This created the need for the B&L to act more like a bank and rely more on staff to assess the quality of loans rather than rely primarily on peer pressure. Moreover, providing dividends to depositors became more important than the original goal of maximizing homeownership.

Mutual savings banks were similar in form to the B&L, except that they were organized primarily to encourage thrift and savings among those of modest means, not for making mortgages. They did, however, have a stimulating effect on mortgage lending because many of their assets were invested in mortgages even before they became direct lenders themselves. Mutual savings banks actually preceded B&Ls in the United States, with states chartering them as early as 1816 (Hoffman 2001, 152). Later, in the 1850s, they entered the mortgage market and soon became the largest source of mortgage funds until surpassed by B&Ls in the 1920s (Lea 1996).

Life insurance and mortgage companies were also important providers of mortgages in the late nineteenth century. Mortgage companies made loans and then sold either individual loans (i.e., what would now be called “whole loan” sales) or bonds backed by the loans to investors (Frederickson 1894; Snowden 2008). However, the bonds sold by mortgage companies were not like the mortgage-backed securities that became so common in the late twentieth century. These bonds more closely resembled corporate bonds because they remained general obligations of the originating mortgage company and the underlying mortgages remained on the books of the mortgage company. However, the mortgages were still pledged as collateral for the bonds. By contrast, modern mortgage-backed securities, which dominated mortgage markets in the 1990s and 2000s, were isolated in “special purpose vehicles” separate from the originating mortgage company. The nineteenth-century mortgage companies also often serviced the loans they originated; because the loans remained on their books, they had more reason to be concerned with the quality of the underlying mortgages than is the case with the later mortgage-backed securities of the late twentieth century that allowed lenders to take loans off their balance sheets. This older type of mortgage bond—often called a debenture or “covered” bond—was not a new innovation in the United States; it had been used in France and Germany from at least the early nineteenth century (Lea 1996; Snowden 2008).

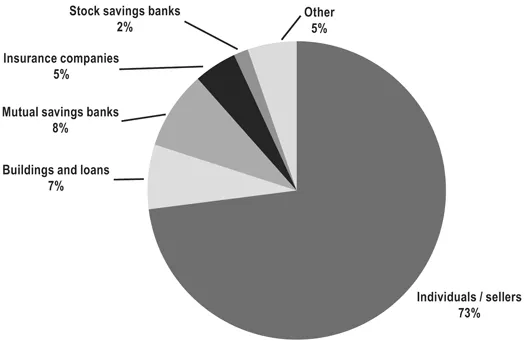

But even with the importation of mortgage bond financing, many loans originated by mortgage companies were sold individually to investors and not financed as bonds as late as the end of the nineteenth century. In an 1894 study of both home and farm indebtedness, Frederickson estimated that a large majority of mortgages were held by individuals, and not by institutions (Frederickson 1894). Figure 1.1 shows that institutional investors accounted for a little over a quarter of mortgage debt held in the United States as of 1892.

Figure 1.1. Holders of mortgage debt in the United States, 1892.

Source: Frederickson, 1894.

Frederickson also examined more closely the locations of investors in seventeen counties across five largely rural states (Alabama, Illinois, Kansas, Tennessee, and Iowa), finding that 48 percent of the debt in these counties was held by residents of the same state as the property. Mortgage agents or companies often originated mortgages but then quickly sold them—often as “whole” loans to individual investors in nearby areas.

Although the source of most mortgage credit in the late nineteenth century was local, at least three sources were not: insurance companies, national building and loans, and mortgage bond investors. Mortgage companies issuing mortgage bonds grew during the 1890s, but largely failed during the recession of the mid-to-late 1890s. Lea (1996) suggests that mortgage bond investors—even in the case of the older debenture-style bonds—suffered from problems of “asymmetric information” vis-à-vis the mortgage company originator selling the bonds. The originator had an incentive to pass off riskier loans as collateral for its mortgage bonds, as purchasers of individual loans were more likely to scrutinize the details of the underlying loan. As we shall see, this is a recurring problem in the buying and selling of loans after they are originated. The selling party often has an advantage in access to information about the loans compared to the buyer, and has a financial incentive not to reveal this additional information. This problem continued into the securitization era and was exaggerated as securitization structures became more complex and less transparent.

The national building and loans also suffered during the economic downturns of the 1890s (Lea 1996; Mason 2004). By the late 1880s, the national B&L had arrived. These entities were typically formed by bankers and industrialists in large cities. They were for-profit lenders whose stock was often closely held. National B&Ls used agents or promoters to sell shares and formed local branches in smaller cities and rural areas. Thus, they were able to pool savings from across disparate and numerous communities, which by themselves may have lacked sufficient capital to constitute strong local B&Ls. Moreover, unlike many local B&Ls, voting control was allocated by share of outstanding stock, giving wealthy founders more control of these organizations. However, the more aggressive profit-seeking nature of national B&Ls was accompanied by higher operating expenses, which ran at 6 to 11 percent of revenues, compared to just 1 to 2 percent for local B&Ls (Mason 2004).

The growth of the national B&L movement was a rapid one. Almost three hundred nationals existed by 1893, and branches of national B&Ls spread to every state (Mason 2004). Their downfall was even swifter. By the late 1890s, failures mounted rapidly. National B&Ls had relied heavily on excessive and sometimes abusive pricing and terms for large portions of their revenue, on both the lending and deposit sides of the business. Later on, it became apparent that the industry was riddled with self-dealing and undue enrichment of officers and executives. Mason (2004) recalls one Minneapolis national that had assets of $2.1 million but spent $1.2 million in expenses in only seven years of operation and another that had only $170,000 of assets but spent $40,000 annually on operating costs.

Mason (2004) argues that a key positive outcome of the national B&L failures was that leaders of the B&L industry became aware of the economic benefits provided by government regulation. They also realized the importance of the need for capital reserves to protect against falling real estate prices.

Despite the failures of national B&Ls and many bond-funded mortgage companies during the 1890s, institutional lenders as a whole rebounded in the early twentieth century (Weiss 1989). Besides local B&Ls, life insurance companies were also significant lenders and managed to avoid many of the problems of other national-scale lenders. While national banks were restricted from making mortgage loans until the 1920s, state banks had begun entering the market. By 1914, 25 percent of loans and 15 percent of state-chart...