![]()

1

DEATH IN STOCKHOLM

Olof Palme was a key player in European politics in the 1970s and 1980s.1 Born in 1928 to a wealthy and distinguished upper-class family, he was educated at a leading private school, where his superior intelligence soon became apparent. Educated at Kenyon College in Ohio and at Stockholm University, Palme dabbled in law and journalism before becoming a leading member of the European student league. He then joined the ruling Social Democratic party and became parliamentary secretary to Prime Minister Tage Erlander in 1953. It has been speculated that Palme’s conversion to socialism was prompted by careerism, although it is fair to point out, as Palme did himself, that his travels as a student leader broadened his views and exposed him to what he called the evils of capitalism and imperialism.

Since the 1930s, the Social Democrats had been in charge of Swedish politics. During these years, the country steadily grew wealthier, poverty was largely abolished, and Sweden’s middle-of-the-road socialism was held up as an example for the rest of Europe. After maintaining a frightened neutrality, Sweden emerged from the Second World War with its industry intact. During the 1950s and 1960s, exports were doing very well, and Swedish steel, paper, cars, and telephones made their impact all around the globe. Taxation was gradually increased, and the money was used to construct an impressive national health service and the most generous social services in the world.

Olof Palme soon became indispensable to Erlander: he acted as a lobbyist and spin doctor, wrote speeches and pamphlets, and spoke in parliament with talent and conviction. Already in the early 1960s, many predicted that he would succeed Erlander. He was hated by the conservatives as a class traitor, and even among his own party colleagues, the distrust of his upper-class origin and university education never completely disappeared. The Swedish parliament at the time was probably the most lackluster in Europe. It recruited its members through central electoral lists rather than through individual elections in the constituencies, and people of outstanding talent and intelligence were few and far between. Through his wealth, intellect, and ambition, Palme stood out as a red carnation among his dull party comrades; he spoke six foreign languages fluently while they could barely express themselves literately in their own awkward tongue. Palme knew well that one of the chief motivating forces for his own electorate was envy and distrust of those who stood out from the crowd. As an antidote, he decided to live very frugally. He bought a small terraced house in a Stockholm suburb and commuted to work on a scooter. His wife, the noblewoman Lisbet Beck-Friis, who shared her husband’s socialist views, supervised him as he washed dishes and ironed laundry. They had three sons and lived a happy family life.

Palme advanced to minister of education, an area where he held strong socialist views. He made drastic changes to the education system, requiring that most Swedes spend eleven or twelve years in school and lowering university standards to accommodate more students. In 1968, as in the rest of Europe, left-wing student uprisings occurred in Sweden, and distrust of the United States, due to the ongoing war in Vietnam, was widespread. Palme feared that this would lead to the rise of the Swedish communist party (subsidized by the Soviet Union, as Palme knew) and took action accordingly. He managed to monopolize the opposition to the Vietnam War by making a series of hostile remarks about the United States, branding the U.S. Army as murderers and likening the war to the Nazi genocide. These ill-judged comments brought him lasting notoriety in the United States, where conservative politicians considered him a dangerous crypto-communist. A photograph of him with the North Vietnamese ambassador in a torch-lit antiwar protest caused more ill will. But it was an oversimplification by his American critics, for Palme was actually a firm admirer of the United States, albeit unimpressed with many of its presidents. He always considered Sweden part of the Western world and was well aware of the Soviet threat.

In 1969, Palme smoothly took over the leadership of the Social Democrats and succeeded Erlander as prime minister. He upheld the view of Sweden as “the People’s Home,” where social classes were abolished, poverty a distant memory, and egalitarianism taken to its logical extreme. The state could always be trusted, the laws were just, and everything could be planned. In the People’s Home, individuals were cared for from cradle to grave by the strong centralized government, whether they wanted it or not. A vast bureaucracy governed the incredibly complicated taxation system; another one, the similarly complex social benefits system. Tax evasion was branded a heinous crime, and accusations of capitalism or profiteering ruined the career of many a promising politician, some of them Palme’s own friends. When Palme was offered the use of a large flat in Stockholm’s historic Old Town by supporters who thought his tiny suburban house wholly inadequate for a distinguished politician, he did not accept it until a lawyer drew up a rental contract that absolved him from any suspicion of undue profiteering.

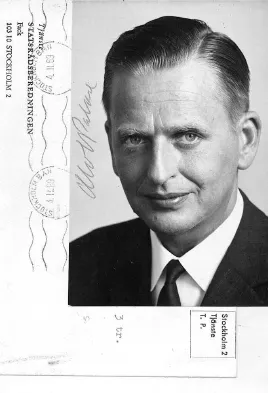

Olof Palme in 1969, an autographed photo.

On the international front, Palme was among the first European leaders to advocate solidarity between the rich, overconsuming Western countries and the third world. He became recognized as an international authority on peace, disarmament, and redistribution of wealth. Sweden was (and still is) a neutral country, wedged between what was then the Western and Eastern blocs, and Palme wanted to make Northern Europe free of nuclear armaments. As an able spokesman against South American dictators and South African apartheid, he gained prestige in socialist circles throughout the world. Almost single-handedly, he made Sweden known throughout the world as a wealthy, advanced democracy that stood for equality, compassion, and humanitarian values. His support for Castro’s Cuba and the communist regime in Nicaragua further blackened his name in the United States, however.

In the mid-1970s, Swedish conservative and liberal parties unleashed a backlash against Palme. Ignoring his international ambitions, they depicted him as personifying a system of rigid socialism and ineffective bureaucracy, a system that rewarded indolence and parasitism while punishing industry and enterprise. Taxation was a key issue, since a middle-class Swede paid seventy percent of his income in tax. Small businesses were literally taxed out of existence. When the celebrated children’s book author Astrid Lindgren questioned whether it was really right that she should pay more than one hundred percent tax on her foreign earnings, Palme’s minister of finance retorted that she should concentrate on writing books and leave matters of state to those who understood them better. Not long after, the minister was himself accused of tax evasion. Sweden had a monopoly on radio and television, and the two state television channels were widely considered the dullest in the world outside the Eastern bloc. More children were taken into care in Sweden than anywhere else, by an army of assiduous social workers. In the state schools (there were almost no private initiatives) the curriculum was experimental in the extreme, to the detriment of general education. And was it really right that young people should earn more on social security than when employed as an apprentice? In the 1976 election, Palme was defeated by a coalition of liberal and conservative parties; he would remain in opposition for six years.

It is a testament to Palme’s strong position within his own party that even after two successive election defeats, there was never any serious debate whether he should resign. Through constant internal bickering, trouble with the powerful trade unions, and various other calamities, the coalition of liberal and conservative parties gradually lost their credibility, and people began to long for Olof Palme’s return: the strong, competent leader and respected international statesman. In 1982, Palme did return to power, and in 1985, he won another convincing victory. At a time when most of Europe’s socialist leaders had been ousted from power, Palme and his Social Democrats appeared stronger than ever. Not a few of these electoral successes were due to Palme’s realization that the rigid socialism of the 1970s had become outdated. He knew that to stay in power, he needed to win the middle-of-the-road vote from the liberals. Despite murmurings among Social Democratic zealots that Palme was tearing down the People’s Home, he appointed a minister of finance with liberal views on taxation, Kjell-Olof Feldt, and some modest tax cuts and other reforms took place. When Feldt and Palme wanted to allow private day-care nurseries as an alternative to the state-run system, another furious debate resulted, from which Palme again emerged unscathed. Another Swedish sacred cow, the immensely powerful trade unions, was a more difficult matter. Wholly unconvinced by Palme’s new liberal policies and provided with ample funds, they openly challenged the government, but Palme did not budge.

Already in the 1970s, Palme had been detested by his conservative opponents; his return to power infuriated these enemies even further. Using his intellectual advantage to mock and taunt his political rivals, Palme had introduced elements of controversy and hatred that had previously been lacking in the quiet pond of Swedish politics. Although popular among his own supporters, and not lacking the common touch, Palme’s arrogant manner and radical socialist rhetoric made him the most hated man in Sweden among right-wing elements. His enemies organized a campaign of vilification against him and delighted in spreading the most extravagant rumors: Palme had extramarital affairs or, alternatively, he was a homosexual. His alleged truckling to the Soviets was particularly unpopular and led to speculation that he took bribes or was a KGB agent. One rumor held that Palme was leading a life of luxury from the ill-gotten gains of wholesale tax evasion, and that his tiny suburban house was connected to vast underground chambers where he sat counting his banknotes. Another ludicrous rumor said that Palme suffered from schizophrenia and that he drove by the lunatic asylum in the morning, before the government meetings, to receive electroconvulsive treatment. The prime minister had really been driving past the asylum, it turned out, to visit his elderly mother in the geriatric ward. Although toughened by years of experience as a controversial politician, Palme was quite upset by this venomous campaign of hatred, particularly when it spilled over on members of his family.

February 28, 1986, began like any other day for Olof Palme.2 He played tennis with his friend Harry Schein in the morning and won a tough game, which pleased him. He then personally went into a haberdashery to exchange a suit he had bought off the rack the day before, because his wife Lisbet had objected to it. His bodyguards accompanied him on both these expeditions and then to Rosenbad, the Swedish government building. Palme then told the bodyguards to make themselves scarce; he would call if he needed them later during the day. He often wanted to maintain his privacy when walking in central Stockholm and disliked the presence of the bodyguards. Had there been any serious threat against him, the bodyguards would have argued for stricter surveillance, but they did not do so.

As Olof Palme arrived at work on February 28, no person noticed anything particular. If anything, Palme seemed quite jolly, as if he was looking forward to the coming weekend. Palme spent the day meeting various diplomats, journalists, and party officials. Just before lunch, he met with the Iraqi ambassador to discuss the ongoing war between Iran and Iraq, in which Palme had the thankless task of being the UN official arbitrator. The ambassador left at 12:00, and Palme briefly met some colleagues before sitting alone in his room until the official government luncheon at 1:00 p.m. It is not known what he did during this time, or whom he might have contacted, since his secretary was herself at lunch. It surprised many people that when Palme at length came into the Rosenbad dining room, he was nearly twenty minutes late and in a furious temper, completely distraught for some unknown reason, and unwilling to tell anyone why. One of the ministers advised him to resort to the traditional Swedish custom of having a “snaps” of aquavit to steady his nerves, but the prime minister angrily declined. In the afternoon, Palme gradually recovered his usual calm and professional manner. A journalist who interviewed him for a trade union magazine even thought that he was in rather a good mood. But when Palme was asked to pose by the window for a photograph, he moodily declined, saying, “You never know what may be waiting for me out there.” This comment struck the journalist as being out of character and in marked contrast to the prime minister’s attitude during the interview.

At the end of the day, Olof Palme walks home to his elegant apartment in the Old Town, not far from the government building. He had previously spoken to Lisbet about going to the cinema in the evening, but they had not decided which film to see. Lisbet originally wanted to see My Life as a Dog, screening at the Spegeln cinema. At 6:30 Olof phones his son Mårten to discuss various things, among them the plans for the evening. It turns out that young Palme is also going to the cinema that evening, to see a film called The Brothers Mozart at the Grand cinema. The Palmes debate whether they should join him. Although Lisbet is still keen on seeing My Life as a Dog, the promise of Mårten’s company might change her mind. They make no promise they will join Mårten, however, and reserve no tickets for either film. In the evening, the Palmes have a bite to eat before going out. During these hours, Palme receives several telephone calls. Two of them, from old party colleagues, have been identified, but there may well have been others. The Palme apartment has only one phone line, and, like any other citizen, Palme answers the phone when it rings, without any secretary or switchboard monitoring the calls. Former party secretary Sven Aspling calls just as Olof is preparing to leave, and Olof ends the discussion by saying that Lisbet is waiting in the hallway, wearing her coat.

As the Palmes step out of the house at about 8:35 p.m., they have finally decided on The Brothers Mozart. A young couple are just passing by the front door. They recognize the prime minister but note nothing untoward, except that when they laugh at some joke, Lisbet looks frightened and surprised, as if she thought they were laughing at her. Neither this young couple, nor several other people who meet the Palmes on their way to the Old Town subway station, notice any person following the prime minister and his wife. Almost everyone who meets him recognizes Olof’s aquiline features, since they have been depicted on the front pages of the Swedish newspapers for more than two decades. Lisbet is much less known among the general public, however. The very antithesis of the glamorous Jacqueline Kennedy, she is short, ordinary looking, and not noted for sartorial elegance. At the subway station, the ticket agent politely wishes Olof Palme a pleasant journey. He finds it odd that no bodyguards are following the prime minister. As the Palmes stand on the platform waiting for the northbound train, quite a few people recognize Olof. Most of them shyly look away, but one or two say hello to the prime minister, who politely returns their greetings. A jolly drunk shouts, “Hey there, Palme, are you taking the subway today?” A man who sees Palme close up marvels at the prime minister’s plain and inelegant clothes, in particular his very creased and baggy trousers. He also gets the impression that Palme is worried about something, since he is moving around nervously on the platform.

Olof and Lisbet Palme after the election victory of 1985.

Finally the train comes in, and Olof and Lisbet enter the third of four subway cars. The train is quite full, and at first the Palmes have to stand; although quite a few people recognize Olof and Lisbet, none of them is chivalrous enough to offer them a seat. A man notices that Palme moves around nervously, as if he were curious about the construction of the subway car. The short subway journey is eventless, and the Palmes emerge from the train at the Rådmansgatan station. As they make their way up the stairs, a mischievous youth recognizes them and decides to walk up behind the prime minister in a threatening manner, to see what the bodyguards will do. He is surprised when nothing happens; not even Palme himself notices him. Neither this youth nor any other witness sees any person following the Palmes as they walk the short distance from the subway station to the Grand cinema.3 Outside the cinema entranc...