II

What Is a Democratic Professional?

Vanessa Gray is a democratic professional. Innovators like her are working in education, journalism, criminal justice, health care, city government, and other fields today. They are democratic professionals not because they do democracy really professionally, but because they do professionalism really democratically. They are democratizing specific parts of our public world that have become professionalized: our schools, newspapers, TV stations, police departments, courts, probation offices, prisons, hospitals, clinics, government agencies, among others. They use their professional training, capabilities, and authority to help people—in Vanessa Gray’s case, students—in their fields of action to solve problems together, and even more important, to recognize the kinds of problems they need to solve. They share previously professionalized tasks and encourage lay participation in ways that enhance and enable collective action and deliberation about major social issues inside and outside professional domains.

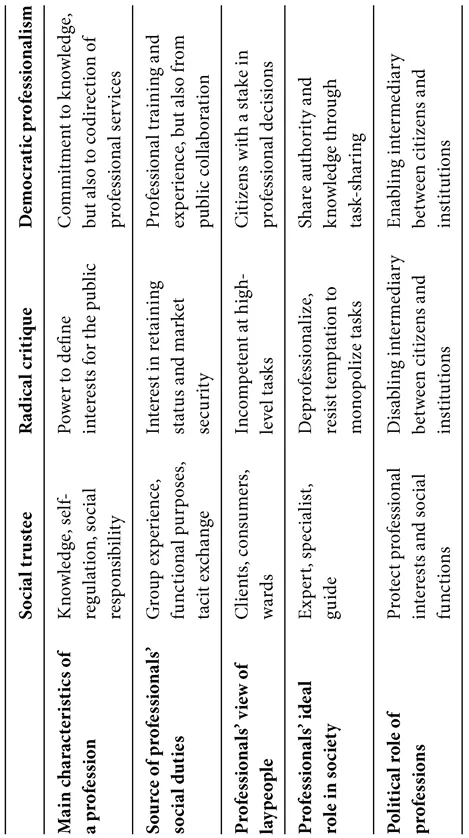

Professionalism, broadly understood, has important meanings and implications for individuals, groups, and society at large. To be a professional is to have a commitment to competence in a specific field of action—you pursue specialized skills and knowledge so you can act well in difficult situations. Professionals understand their work as having an important normative core: beyond simply earning a living, the work serves society somehow. Sociologists of the professions stress the ways occupations draw boundaries around certain tasks, claim special abilities to handle them, police the ways in which they are discharged, and monitor education and training. Democratic professionalism is an alternative to a conventional model of professionalism I call social trustee professionalism, yet it is also different from some other approaches critical of professional power, which I call the radical critique.

The social trustee ideal emerged in the 1860s and held prominence for a century among traditional professions such as law and medicine as well as aspiring professions such as engineering and social work. It holds that professionals have a more general responsibility than just a fiduciary or function-specific obligation to their clients.4 Of course, professionals are obligated to competently perform their tasks, but they also have general responsibilities that stem from their social status, the trust clients place in them, and the market protection governments have permitted them through licensing and other regulations. As Talcott Parsons put it, “A full-fledged profession must have some institutional means of making sure . . . competence will be put to socially responsible uses.”5 For example, the medical profession heals people, but it also contributes to the larger social goals of curing disease and improving public health. And the legal profession, besides defending their clients’ rights, also upholds the social conception of justice.

Social trustee professionals may represent public interests in principle, but in fact this representation is very abstract. Serving “the community” is not seen by professionals as something that requires much say from diverse members of actual, present-day communities. Under the terms of the social trustee model, professionals serve the public through their commitment to high standards of practice, a normative orientation toward a sphere of social concern—doctors and health, lawyers and justice—and self-regulation. The model is held together on the basis of an economy of trust: the public trusts the professionals to self-regulate and determine standards of practice, while the professionals earn that trust by performing competently and adhering to the socially responsible normative orientation. Those public administrators, for example, who see themselves as social trustees assert quite straightforwardly that they are hired to manage issues for which they have specialized training—public budgeting, town planning, and the orchestration of service provision, among others. If their communities disapprove of the way they do their jobs, they can fire them, but true professionals do not need to listen to their communities.

A radical critique emerged in the 1960s, drawing attention to the ways professions can be impediments to the democratic expression of public interests rather than trustworthy representatives. Though aware of the benefits of modern divisions of labor that distribute tasks to different groups of people with specialized training for the sake of efficiency, productivity, and innovation, critics like Ivan Illich and Michel Foucault worried about task monopolies secured by professionals that block participation, shrink the space of democratic authority, and disable and immobilize citizens who might occupy that space.6

Professions shrink the space of democratic authority when they perform public purposes that could conceivably be done by laypeople—as doctors aid human welfare and criminal justice administrators serve needs for social order. Critics stressed that these services and products have public consequences: how they are done affects people not just as individuals but also as members of an ongoing collective. And sometimes professionals quite literally shrink the space of participation by deciding public issues in institutions, far from potential sites of citizen awareness and action. Think of how health care professionals promote certain kinds of treatment and healing over others and how criminal justice professionals construct complex anger management and life-skills programming for convicted offenders. Professionals can disable and immobilize because, in addition to taking over these tasks, their sophistication in, say, healing or sentencing makes people less comfortable with relying on their own devices for wellness and social order. Professions are professions by virtue of their utilization of abstract, specialized, or otherwise esoteric knowledge to serve social needs such as health or justice. The status and authority of professional work depend on the deference of nonmembers—their acknowledgment that professionals perform these tasks better than untrained others. But with deference comes the risk that members of the general public lose confidence in their own competence—not only where the task itself is concerned, but for making informed collective decisions about issues that relate to professional domains of action.

How can professional actors help mobilize rather than immobilize, expand rather than shrink democratic authority? The radical critique leaves this question largely unexplored. Critics offer few alternatives to social trusteeism for reform-minded practitioners who wish to be both professional and democratic: to deprofessionalize or to develop highly self-reflective and acutely power-sensitive forms of professional practice that draw attention to the ways traditional practices and institutions block and manipulate citizens. Yet these reform suggestions fail to register the ways professional power can be constructive for democracy. To the extent that professionals serve as barriers and disablers, they can also, if motivated, serve as barrier removers and enablers. Especially in complex, fast-paced modern societies, professional skills and knowledge help laypeople manage personal and collective affairs. What we need is not an anti-professionalism, but a democratic professionalism oriented toward public capability.

Table 1: Models of professionalism

So, how might democratic professionals go about their work? While heeding the conventional obligation to serve social purposes, they also seek to avoid perpetuating the civic disenfranchisement noticed by radical critics of professional power. Democratic professionals relate to society in a particular way: rather than using their skills and expertise as they see fit for the good of others, they aim to understand the world of the patient, the offender, the client, the student, and the citizen on their terms—and then work collaboratively on common problems. They regard the layperson’s knowledge and agency as critical components in resolving what can all-too-easily be seen as strictly professional issues: education, government, health, justice, and more.

Two Paths of Democratic Change

Democratic professionals in the United States and elsewhere are already creating power-sharing arrangements in institutions that are usually hierarchical and nonparticipatory. They can help us understand the resources available right now for deep cultural change. To appreciate this, however, we must release ourselves from the grip of the prevailing view of how and where democratic change happens.

Drawing on the historical precedents of abolition, women’s suffrage, labor reform, civil rights, and student movements, discussion of democratic change typically focuses on the power of people joined together in common cause to press for major legislative action. Core factors in the process include leadership, mobilization, organizational capacity, consciousness-raising, forms of protest such as strikes, marches, and sit-ins, and electoral pressure on political parties and candidates.

While our default perspective is crucial for understanding some types of democratic action, it is state-centric and privileges resources that are exogenous to daily life. In this first path to democratic change, political action appears as a burst of collective energy that then dissipates after certain legal or policy targets are met: slavery abolished, voting rights for women established, the eight-hour workday guaranteed, military conscription for Vietnam ended. A large-enough number of people temporarily leave their everyday routines to join a collective effort. For this reason, some scholars call democratic movements “fugitive,” since at the end of the protest or campaign, most people return home, leaving the business of government to insiders.7

Less noticed are the alterations democratic professionals make to their institutions as they break down internal hierarchies and foster physical proximity between people, encourage coownership of problems previously seen as too complex for laypeople, and seek out opportunities for collaborative work. We fail to see these activities as politically significant because they do not fit our conventional picture of democratic change.

The reformers I have interviewed in my ongoing research on democratic professionals in criminal justice, public administration, education, and other fields rarely use social science or political theory concepts. Lacking ideology, they make it up as they go along, developing roles, attitudes, habits, and practices that open up rigid structures to greater participation. In this second path to democratic change, democratic action is endogenous to an occupational routine, often involving those who would not consider themselves activists—or even engaged citizens. Though they often belong to practitioner networks, the innovators I have met do not form a typical social movement. Rather than mobilizing fellow activists and putting pressure on government office-holders to make new laws or rules, democratic professionals make changes in their domains themselves, piece by piece, practice by practice. In the trenches all around us, they are renovating and reconstructing schools, clinics, prisons, and other seemingly inert bodies.

In State College, Pennsylvania, principal Donnan Stoicovy turned her kindergarten-through-fifth-grade schoo...