![]()

[1]

Defining and Explaining Civilian Victimization

What is civilian victimization, and why do governments victimize civilians in warfare? I begin by defining the concept of civilian victimization, the phenomenon I seek to explain in this book. Civilian victimization is a military strategy chosen by political or military elites that targets and kills noncombatants intentionally or which fails to discriminate between combatants and noncombatants and thus kills large numbers of the latter. I then outline the common forms of civilian victimization and provide illustrative examples.

In the second part, I summarize three competing perspectives on civilian victimization: regime type, civilized-barbaric identity, and organization theory. The regime-type view maintains that domestic norms and institutions are the most important causes of civilian victimization. The civilized-barbaric identity argument, by contrast, contends that states kill an adversary’s noncombatants when they view the enemy as outside the community of civilized nations. Organization theory, finally, suggests that the cultures or parochial interests of military organizations are the prime causes of civilian victimization.

The third section presents my theory of civilian victimization, which identifies two crucial factors: the growing sense of desperation to win and to conserve on casualties that states experience in protracted wars of attrition, and the need to deal with potentially troublesome populations dwelling on land that an expansionist state seeks to annex. I discuss the logic underpinning these two factors and the differing implications they have for the timing of civilian victimization. I also explain why targeting civilians—even though it does not always work—is not an irrational gamble, but rather a calculated risk. I conclude with a short discussion of methods and cases.

Defining Civilian Victimization

Civilian victimization as I define it consists of two components: (1) it is a government-sanctioned military strategy that (2) intentionally targets and kills noncombatants or involves operations that will predictably kill large numbers of noncombatants. Civilian victimization violates the principles of noncombatant immunity and discrimination as enshrined in the Geneva Conventions and just-war theory, which require that belligerents must distinguish between combatants and noncombatants and refrain from taking aim at the latter.1 Common forms of civilian victimization include aerial, naval, or artillery bombardment of civilians or civilian areas; sieges, naval blockades, or economic sanctions that deprive noncombatants of food; massacres; and forced movements or concentrations of populations that lead to widespread deaths. As with Benjamin Valentino’s definition of mass killing, civilian victimization “is not limited to ‘direct’ methods of killing, such as execution, gassing, and bombing. It includes deaths caused by starvation, exposure, or disease resulting from the intentional confiscation, destruction, or blockade of the necessities of life. It also includes deaths caused by starvation, exhaustion, exposure, or disease during forced relocation or forced labor.”2

Several aspects of civilian victimization bear elaboration. First, in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, I define combatants as “all organized armed forces, groups and units which are under a command responsible to that Party for the conduct of its subordinates,” as well as individuals involved in the construction of weapons.3 Noncombatants, by contrast, do not participate in armed conflict by fighting, carrying weapons, serving in the uniformed military or security services, or building weapons. Two general principles can be used to demarcate the line between combatants and noncombatants. One view, articulated by Michael Walzer, maintains that people have the right to be free from violence unless they forfeit that right by participating in military activity, such as taking up arms or working in a munitions factory. As Walzer puts it, “No one can be threatened with war or warred against, unless through some act of his own he has surrendered or lost his rights.”4 A second perspective focuses on the degree of threat an individual poses to the adversary to draw the combatant/noncombatant line. Only those individuals who actively participate in hostilities—by serving in the armed forces, for example—constitute an immediate threat of harm to the enemy and thus qualify as combatants.5 I argue that individuals who build bombs and other munitions also pose a significant threat of harm and should thus be included in the combatant category. If they are not, attacks on munitions factories (or targeted killings of terrorist bomb-makers, for that matter) would have to be classified as intentional targeting of civilians. This violates the common-sense understanding that such individuals are not owed the same degree of protection as those employed in other sectors of the economy, and that killing them is not morally wrong.6 Thus, whichever of these general principles one subscribes to, both point to an understanding of noncombatants as outside the realm of military activity either as fighters or makers of weapons.

Skeptics contend that nationalism and industrialization have eliminated the noncombatant category altogether because all citizens in modern states contribute to the war effort if only by going to work, paying taxes, or consenting to the use of force.7 This view clashes with the obvious fact that even in modern societies, there are many people who contribute little if anything to the war effort, and further that this relative disengagement (and absence of threat) makes a difference as to whether they may be killed.8 Many individuals work in sectors of the economy unrelated to the war effort; some, particularly children and the elderly, do not work at all. One study estimates that 75 percent of the population of an industrial country does not labor in war-related industries, and that even in industrial cities, 66 percent of the inhabitants are civilians.9

Second, civilian victimization is a government-sanctioned policy or strategy, as opposed to random or uncoordinated attacks by a few military units. Intentional attacks on civilians, as Christopher Browning has pointed out, can take the form of arbitrary explosions of violence or revenge inspired by “battlefield frenzy,” on the one hand, or can represent “official government policy” or “standing operating procedure,” on the other hand.10 Only the latter comprises civilian victimization as defined in this book: it consists of a government policy of sustained violence against a noncombatant population, rather than haphazard outbursts of brutality by frustrated troops. This does not mean, however, that civilian victimization must be initiated by civilian leaders; in fact, it is sometimes initiated by the military on the ground, but once political leaders become aware of the strategy and approve it—or decline to stop it—it becomes de facto government policy.11

Third, civilian victimization consists of strategies that intentionally target civilian populations but also strategies that—although not purposefully aiming at noncombatants—nevertheless fail to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants. A strategy of civilian victimization, in other words, either targets civilians on purpose, or employs force so indiscriminately that it inflicts large amounts of damage and death on noncombatants. In certain cases, for example, belligerents openly declare or make statements of policy that designate noncombatants as the target of a strategy. British bombing policy in the Second World War, which charged Bomber Command with destroying urban areas in Germany to undermine “the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular, of the industrial workers,” falls into this category.12 British policy clearly meant to kill German civilians in order to bring about the collapse of Germany’s will to fight. The 300,000 fatalities caused by this strategy were not a side-effect of strikes on military targets, or a product of a refusal to discriminate between soldiers and civilians, but rather the intended object of the strategy.

In other cases, however, belligerents mount a pattern of repeated attacks over an extended period that fail to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants and thus kill tens of thousands of civilians. Although killing noncombatants is not the avowed purpose of such a strategy, this outcome is nevertheless foreseeable, predictable, and often desired, and thus constitutes civilian victimization. The U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, for example, launched seventy self-described attacks on a “city area” in Germany, raids that qualify as intentional civilian victimization. United States bombers also devoted about half of their total effort to radar bombing, which—although not purposefully directed at civilians—American military officers knew was the functional equivalent of British area bombing. According to Thomas Searle, “USAAF commanders essentially acknowledged this fact by using a large percentage of incendiary bombs (the preferred weapon against cities) on these raids even though such bombs were ineffective against rail yards, the official targets.”13 The adoption and exploitation of this indiscriminate form of attack thus constitute civilian victimization.

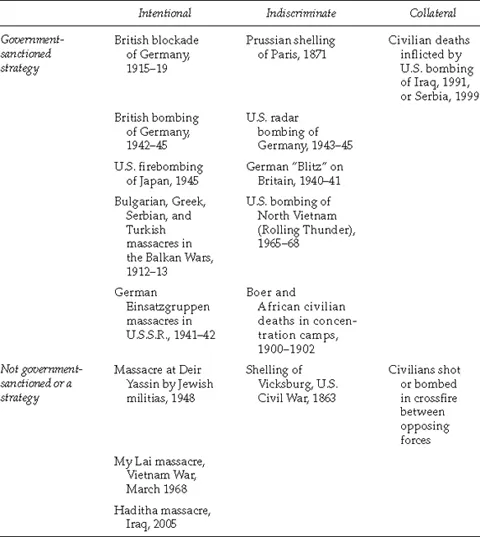

Contrast each of these strategies with the U.S. strategic bombing campaign during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. In that conflict, for example, F-117 aircraft bombed the Al-Firdos bunker in Baghdad, an installation that U.S. air planners believed was a command-and-control center. Unknown to these planners, however, the Iraqi regime was using Al-Firdos as a bomb shelter for civilian dependents of Iraqi officials. The air strike killed approximately two hundred to three hundred civilians. These deaths, although tragic, did not result from a government policy of targeting noncombatants. Nor did the casualties stem from a refusal to discriminate between soldiers and civilians, as the U.S. military did not even know there were noncombatants present at the target. Moreover, immediately after the Al-Firdos disaster, U.S. officials declared Baghdad off-limits to further air strikes, and few targets were struck in the Iraqi capital for the remainder of the war.14 Table 1.1 highlights the differences among these types of violence and provides examples of each.15

Table 1.1. A typology of civilian casualties

Clearly there are cases in which establishing the intentionality or deliberateness of civilian victimization is harder than in the British case. Policymakers do not always speak openly or truthfully when it comes to killing innocent people: there is no mention in the memoirs of British leaders, for example, that the policy of blockade in World War I was meant to starve the German people. President Truman, moreover, spoke of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as purely military targets.16 These cases highlight the importance of examining internal government documents and private communications whenever possible to supplement leaders’ official pronouncements. They also underline the importance of observing behavioral indicators that may indicate a shift toward civilian victimization—increasing indiscriminateness, decreasing concern for civilian life, or variation in the types of weapons used (incendiary versus high explosive bombs, for example).

Other analysts have chosen to include only intentional civilian deaths in their studies. Kalyvas, for example, looks only at the deliberate killing of noncombatants—homicide—excluding deaths inflicted unintentionally (collateral damage) and nonviolently (famine and disease). Valentino also focuses on intentionality, differentiating intentional from unintentional deaths based on the civilian or military nature of the target: when the target is military, civilian deaths are always unintended; when the target is civilian, deaths are always intended.17 This definition undesirably stretches the concept of intentionality. Valentino, for example, argues that if noncombatants are the direct object of the policy, their deaths should be considered intentional if they are a foreseeable result of the policy. But this statement equates the mere knowledge that civilians will die with intending or desiring their deaths. Valentino thus contends that the fatalities of Boer women and children in British concentration camps during the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) were intentional because the civilians themselves were the object of the policy. This judgment is belied by the evidence, however, which shows that British officials did not purposefully try to kill these people, or hope to bring about the deaths. According to historian Thomas Pakenham, “Kitchener no more desired the death of women and children in the camps than of the wounded Dervishes after Omdurman, or of his own soldiers in the typhoid-stricken hospitals of Bloemfontein. He was simply not interested.”18 Civilians were the direct object of the reconcentration policy, but this does not necessarily make their deaths intentional.

Valentino also excludes from his definition all civilian fatalities that result from strikes on military targets, deeming these casualties to be unintended collateral damage. This, too, involves conceptual stretching, this time of collateral damage. When a strategy ostensibly directed at military targets generates tens of thousands of noncombatant fatalities, can these deaths still be considered collateral? Excluding these cases also ignores substantial evidence that some attackers simply did not make any attempt to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants, did not care that large numbers of civilians were being killed, or sought to capitalize on the fear these deaths created among the enemy population.

I argue, therefore, that civilian victimization should include all cases where it can be determined that belligerents intended to kill an adversary’snoncombatants, but it should not be limited to such cases. The concept should also include strategies that cause large numbers—tens of thousands—of civilian deaths owing to belligerents’ inability or refusal to discriminate between combatants and noncomb...