![]()

ONE

Contention Unending

Adat basandi syarak dan syarak basandi adat.

Custom is based on Islamic law and Islamic law is based on custom.

Minangkabau aphorism

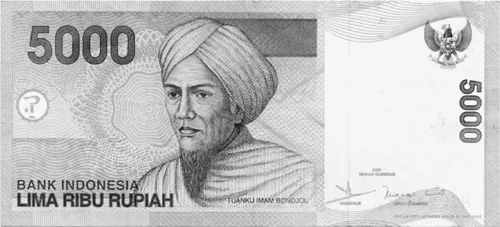

In 2001, the Indonesian National Bank issued a note featuring a portrait of a stern man with a long beard, wearing a turban and a white robe thrown back over his left shoulder (figure 1.1). Tuanku Imam Bondjol was the formal title given to this man, whose name was Muhamad Sahab and who as a young adult had been called Peto Syarif; he was born in the Minangkabau region of West Sumatra about 1772 and died outside of the city of Manado in North Sulawesi in 1854. Tuanku was a title given to high-ranking ulama in West Sumatra. Imam, religious leader, usually refers to some individual characteristic of the ulama. Of the (at least) fifty tuanku who were contemporaries of Tuanku Imam Bondjol, we find Bachelor Tuanku, Little Tuanku, Fat Tuanku, Black Tuanku, Old Tuanku, and so forth. Bondjol is the old spelling of the town of Bonjol, where the Tuanku Imam established his fortress and from 1833 to 1837 led the fight against Dutch annexation of the Minangkabau highlands. I follow Indonesian convention and use the old spelling of Bondjol for the man and Bonjol for the village.

Like Agus Salim, Hatta, Sjahrir, and others, Tuanku Imam Bondjol is an official Minangkabau national hero but from a prenational era. He is also a putative Wahhabi and leader of the Padri War, which is described as the first Muslim-against-Muslim jihad in Southeast Asia. My understanding of the war is based first on the memoir of Tuanku Imam Bondjol himself. The other major Minangkabau source for the history of the Padri War is an autobiographical note by the moderate religious scholar Syekh Jalaluddin, written at the request of the colonial administration in the late 1820s. Jalaluddin was persecuted by the Padri, and his text provides the history of Islamic reform in the late eighteenth century as well as a critique of the Padri from within the reformist movement. Along with this clarification by Syekh Jalaluddin, Imam Bondjol’s memoir stands as one of the first modern Malay autobiographies. In their memoirs, Jalaluddin and Imam Bondjol are the textual ancestors of the schoolschrift writers. The texts exhibit an emotional resonance that comes perhaps from being written simultaneously for a Dutch contemporary audience and for Minangkabau posterity, from the perspective of a villager, not a courtier, and of a Muslim reformist concerned especially with family structure and everyday life.

Figure 1.1. Tuanku Imam Bondjol, as depicted on the 5,000-rupiah banknote.

Islam before the Padris

Islam came to West Sumatra in the 1500s, delegitimizing animism and Buddhism in a process that has yet to be understood fully. An early-sixteenth-century account reported that at least one Minangkabau king had recently converted to Islam. And Thomas Dias, a Portuguese mestizo who visited the highlands in 1684, reported seeing hajjis at the royal court. Minangkabau experienced the organized and institutional drive to convert to Islam only in the seventeenth century, when a central Sufi tarekat (mystical association) was established on the coast at Ulakan. Azyumardi Azra claims that the “embers of reformism” were first stoked in the late 1600s when members of the Ulakan student network observed with disappointment the overexuberance of their fellows commemorating the death of the founder of the tarekat.

In the eighteenth century, American and European demand for coffee, pepper, and cassia created a boom in the highland economy that disrupted traditional trading systems and brought new intellectual influences through the port of Tiku, near Ulakan. Marginal villages with poor soil became wealthy by planting the new cash crops, threatening the influence of the traditionalist wet rice farmers. Many of the Muslim reformists came from these newly rich villages.

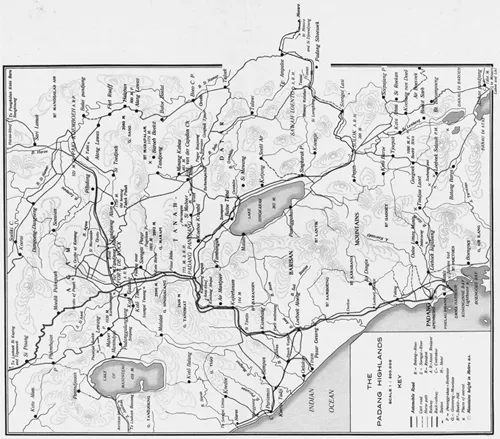

By the later eighteenth century, Islamic reformism had followed the Naksyabandiyah, Syattariyah, and Qadiriyyah tarekat into the highlands, and the Islamic school headed by Tuanku nan Tuo became a center for the reformist movement. Syekh Jalaluddin remembered his father’s stories of the ante-bellum 1780s and the religious changes already underway in Minangkabau. He described the religious conditions in Minangkabau in the late eighteenth century, when his father was an Islamic reformist and educator. Already in the 1780s, centralizing religious schools were spreading throughout the highlands. The reformists moved from the old Sufi-influenced school at Ulakan, near the coastal town of Pariaman, traveling through Kamang and Rao in the highlands, stopping briefly in Koto Gadang, and finally settling in Batu Tebal (figure 1.2), where eventually they garnered enough support to maintain the forty-man congregation necessary for Friday prayers.

It would be a mistake to imagine that religious education in pre-Padri, precolonial Minangkabau was entirely localized and focused on village prayer-houses. Religious scholars advertised experiences and connections in the religious centers of Mecca, Medina, and even Aceh—the world of Islamic learning was inherently cosmopolitan. Reformists were beginning to make inroads into the heartland. And important tarekat centers, with particularly potent teachers, had long attracted supplicants.

Attentiveness to private life and daily behavior was a novelty in the Islamic world in the late eighteenth century. Through the early 1700s Islam and the ulama had been primarily concerned with states and with kingship. The new reformist Islamic movements were more involved with the everyday lives of ordinary people; fataawa addressed issues of family life, of sex, of appropriate conduct. From West Africa through South Asia and into the Malay world, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries brought local Muslim reformist and revivalist movements that shared common objectives and similar violent rhetoric. But although the Padris had many contemporaries, they were more profoundly in opposition to local custom than their counterparts were; Minangkabau matrilineal inheritance and matrilocal residence were affronts to shariah law that were impossible to ignore. There were consequences to this new discourse on private life. In Indonesia, an attentiveness to the family and to daily life in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries presaged what in the early twentieth century became known as the moderen. In the nineteenth century, a public sphere for Islam developed around concerns that the colonial state did not share (although the Dutch, and to a lesser extent the British, did attempt to control the private lives of their subjects). Muslims were kept out of politics—in the Dutch East Indies, hajji were barred from serving in the colonial civil administration—but they were political regarding social issues. From Mecca at the end of the nineteenth century, the Minangkabau Sheikh Ahmad Khatib would rail against matrilineal inheritance in his homeland. His students and readers became the core of the early-twentieth-century reformist movement. When in the early twentieth century the colonial state tried to introduce nominal participatory politics to its “native” subjects, they expected a long tutelary process. But for the ulama no learning curve was needed for civil behavior, and they plunged into the political sphere fully fledged.

Caught up in the wave of eighteenth-century Islamic reformism, Tuanku nan Tuo, a moderate reformist around whom the future Padri coalesced, pushed for a stricter application of Islamic law, better attendance at Friday prayers, an end to gambling and drinking, and a cessation of the brigandage and slaving that had come with increased trade. That trade also brought new wealth, and more people had the means to undertake the hajj pilgrimage. The Hijaz and Mecca were tumultuous in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. From the final decade of the eighteenth century, the Wahhabis were involved in a campaign of conquest there, temporarily occupying Mecca in 1803 and capturing the city from 1806 through 1812. Wahhabi followers reject textual interpretation as innovation and demand adherence to a way of life that follows the Quran and the authoritative Hadith. In the Hijaz, the Wahhabis burned books, demolished domes, destroyed tombs and pilgrimage sites, and, according to one unimpressed scholar, engaged in a “campaign of killing and plunder all across Arabia.”

Some time after the 1803 Wahhabi occupation, three Minangkabau hajji returned from Mecca, where, according to every history, they had been influenced by the teachings of the conquering army. It is impossible to know with any certainty whether the three hajji were directly influenced by Wahhabism while in Mecca. What is clear is that for these returning hajji traditional Minangkabau culture was unacceptable; matriliny and matrilocally constituted longhouses could not be reconciled with the essential teachings of Islam. One of the hajji, known as Haji Miskin, allied with more impatient reformists in Tuanku nan Tuo’s circle and established walled villages, grew beards, wore robes and turbans, and attempted to recreate an Arabian culture in highland West Sumatra. This combination of localized reformism and Wahhabi-like influence became known as the Padri movement.

Figure 1.2. Map of the Padang Highlands in 1920. The Official Tourist Bureau, May 1920.

In a violent affront to the Minangkabau matriarchate, an extremist Padri, Tuanku nan Renceh, murdered his maternal aunt. The Padri declared a jihad against the traditional matrilineal elite, burning longhouses (rumah gadang) and killing traditional leaders who upheld custom (adat) in the face of religious commandments. The Padri War was a protracted series of conflicts, and the Padri “state,” influenced by the decentralized and democratic traditions of Minangkabau polities, lacked a clear administrative hierarchy. The decentralization of authority allowed for a natural sort of guerilla warfare that did not encourage climactic or pyrrhic battles. In 1815, the Padris, using peace talks as a ruse, slaughtered the royal house of Pagaruyung near Batusangkar. They turned against Tuanku nan Tuo and Syekh Jalaluddin, the moderate reformists, calling the men Rahib Tuo (old Christian monk) and Rajo Kafir (King of Infidels).

For twenty years, sporadic fighting between reformist and traditionalist forces destabilized West Sumatra. Eager to rehabilitate the economy of the Netherlands in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars (and moreover after the secession of Belgium in 1830) and lured by rumors of gold and the power of the Minangkabau court, in 1821 the Dutch colonial government returned to the port of Padang, signed a treaty with the traditionalists, and sent an army into the hills. It is at this point that the extensive Dutch archive takes control of the historiography of the Padri War.

According to this history, a series of treaties and perceived betrayals on all sides of the conflict punctuated twelve years of difficult fighting. But in 1830 the Dutch were able to reinvigorate their army with Dutch and Javanese troops fresh from victories over Diponegoro, and by 1832 the Dutch had defeated Bonjol and apparently incorporated West Sumatra into their burgeoning colony. The collapse of the Padri in 1833, however, was followed by a unification of the reformist Muslims and matrilineal traditionalists in a revitalized resistance to foreign occupation. Six more years of violent warfare ensued, and by 1838 the Minangkabau were defeated, their leaders killed or, like Tuanku Imam Bondjol, exiled...