1

THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS OF REFUGEE PROTECTION

The causes and consequences of human displacement are highly political, and refugee issues are by definition international in scope. People who flee persecution by crossing international borders generally do so because of political causes such as conflict or internal repression. The influx of refugees into a state has implications for security and the distribution of resources within that state. Furthermore, refugees’ access to protection while in exile and long-term solutions to their plight are a consequence of political decisions and nondecisions.

Nevertheless, despite the inherently political and international nature of refugee protection, there has been surprisingly little attempt by academics working on refugee-related issues to draw on IR theory to understand the international politics of refugee protection. Nor has there been much attempt by IR to bring issues of refugee protection into the discipline and to explore what they can offer for the reconsideration of IR theory. In contrast to the work that has been done in issue areas such as the environment, human rights, and trade, refugee protection has largely been invisible within mainstream IR.

Only isolated pockets of scholarship have emerged, drawing selectively on insights from different areas of IR. There have been some theoretical attempts to examine refugee issues from a state security or human security perspective (Milner 2000; Newman and Van Selm 2003; Weiner 1996), the international political economy of the refugee regime (Castles 2004), the relationship between conflict and displacement (Lischer 2005; Salehyan and Gleditsch 2006; Stedman and Tanner 2003), the role of UNHCR (Barnett and Finnemore 2004; Loescher 2001b; Loescher, Betts, and Milner 2008), and the position of refugees in relation to the state system (Haddad 2008). Yet much of the work on the politics of refugee protection has come from lawyers or sociologists rather than political scientists. Generally, the most acclaimed work on the IR of refugee protection has been historical and descriptive rather than drawing on the conceptual tools provided by IR (Gordenker 1987; Loescher and Monahan 1996; Skran 1995; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo 1989). Few mainstream IR scholars have devoted time to considering the international politics of refugee protection,1 and in forced-migration studies, the majority of the work has been from the perspective of the displaced and draws mainly on disciplines such as anthropology, geography, and sociology.

Yet exploring the international politics of refugee protection is extremely important both for theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, analyzing an unexplored area of world politics has great potential for challenging and developing the core concepts of IR. Refugee protection is an issue that potentially offers insights for a range of key themes in IR, such as international cooperation, the role of international organizations, globalization, security, and conflict. From a practical perspective, anyone who wishes to understand or influence the behavior of states toward refugees must first understand the conditions under which states are and are not willing to contribute to refugee protection. Although many people who work with refugees and forced migrants might argue for the need to take a grassroots perspective and understand the experiences of the displaced, analyzing forced migration at the level of the state and interstate politics is at least as important for anyone who wishes to understand the reasons why refugees do or do not receive access to international protection (Landau 2007).

Refugee Protection as a Global Public Good

In the little academic work that exists on international cooperation in the refugee regime, it has been suggested that refugee protection is a global public good (Suhrke 1998). A public good is a good that has the properties of nonexcludability and nonrivalry. In other words, once provided, the benefits conferred by the good (1) cannot be excluded from all the other members of the community and (2) do not diminish or become scarce when enjoyed by another actor. In domestic politics, a classic example of a public good is street lighting. Because of their characteristics, public goods such as street lights present a particular challenge to ensuring that they are adequately provided. Although all members of a community would want street lights and might be prepared to pay their share, no one individual would be prepared to provide the street lights alone knowing that everyone else would benefit without paying. When public goods such as street lights are not provided by a central authority, they are likely to be underprovided relative to the community members’ collective interest because, individually, people have a strong incentive to free-ride on other people’s contributions. In domestic politics, the collective action failure that results from public goods is generally addressed by the state; governments pool the resources of citizens and ensure that public goods are provided.

At the global level, in the absence of a world government, the provision of global public goods presents a greater challenge. As with domestic public goods, such as street lights, global public goods are characterized by nonexcludability and nonrivalry. And, as with the citizens in our domestic public goods example, states may value the provision of a good and, acting collectively, would choose to provide the goods but not be prepared to provide it unilaterally if they believe that their contribution is not tied to the contributions of other states and that they can simply free-ride on the contributions of other states. Consequently, the overall level of provision will be suboptimal relative to how states would have acted had their actions been coordinated. This disjuncture between how states act collectively and how they act independently is referred to as collective action failure. It is commonly illustrated using the game theoretical analogy of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, which highlights the divergence between how actors behave when they coordinate their behavior and how they behave when they make decisions individually (Olson 1965).

In world politics, a number of issues that are global in scope (that is, that affect all states) have been identified as global public goods. The provision of goods such as climate-change mitigation, the eradication of communicable disease, the international monetary system, global security, nuclear nonproliferation, and asteroid risk mitigation have all been analyzed from the perspective of global public goods. These issues have in common that, because their benefits are available to all states, irrespective of which states provide the goods, states have a tendency to free-ride on the contributions of other states rather than contributing to the cost of provision themselves. The challenge for policymakers has therefore been how to devise institutions at the global level that ensure that collective action failure is overcome and that these goods are provided (Barratt 2008; Boyer 1993; Kaul, Grunberg, and Stern 1999).

In general, the international politics of refugee protection has not been integrated into the mainstream study of global public goods. One of the very few exceptions to this general absence of conceptual work on the international politics of refugee protection is the path-breaking work of Astri Suhrke, who has argued that the provision of refugee protection may be considered a global public good. Because refugee protection is collectively valued by states but the benefits it provides are available to all states, irrespective of who provides, Suhrke suggests that states tend to free-ride on the provision of other states. As she explains, this means that, because the costs of providing protection are borne by individual states but the benefits accrue to all states even if they do not contribute, the refugee regime is likely to be characterized by collective action failure (Suhrke 1998).

Indeed, the availability of refugee protection can be thought of as providing two nonexcludable benefits to states: order and justice. Both of these benefits were explicitly recognized as the reason that it was important to create a global refugee regime at the time of the negotiation of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Refugee protection contributes to international order;2 it ensures that individuals whose rights are not provided by their own nation-state can be reintegrated into the nation-state system. From the perspective of states, the availability of refugee protection is therefore of value because it prevents people who cross boundaries to flee conflicts and human rights abuses from becoming stateless. This reduces the likelihood that they, in turn, become a source of conflict or insecurity. The absence of effective refugee protection has been associated with the recruitment of refugees by guerrilla movements and terrorist organizations, for example (Juma and Kagwanja 2008; Lischer 2005; Morris and Stedman 2008; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo 1989). Refugee protection also contributes to international justice;3 it ensures that, even when states cannot or will not ensure the human rights of their citizens, these values are nevertheless upheld through their being accorded to refugees by another state. Because both these benefits are available to other states, even if they do not actually contribute to refugee protection themselves, international order and justice may be thought of as the public benefits that come from the provision of refugee protection.

In practice it is unlikely that these nonexcludable benefits will accrue equally to all members of the international community. Some states—especially those with greater proximity to a given refugee outflow—will benefit more greatly from a neighboring state’s contribution to refugee protection than would a more distant or disinterested state. In other words, the benefits of refugee protection are more likely to be a regional public good than a global public good. Nevertheless, the public goods concept is valuable insofar as it highlights that the partly nonexcludable nature of many of the benefits of protection may lead to free-riding.

The Refugee Regime as a Prisoner’s Dilemma

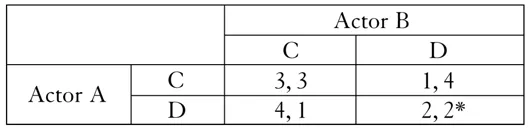

The public-goods nature of the benefits of international order and justice means that these benefits are available to states even if they free-ride on the contribution of other states. For this reason, Suhrke claims that, in the absence of a binding institutional framework at the global level, refugee protection will be characterized by collective action failure. She illustrates this using the game theoretical analogy of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which, in a two-actor model, each of two states may prefer mutual cooperation (CC) to mutual defection (DD) yet one state may be even better off when it can benefit from the unrequited cooperation of the other actor (DC). However, being the state that behaves cooperatively without a reciprocal response (CD) is the least desirable outcome. Consequently, the preference ordering of states is DC > CC > DD > CD. In a single interaction, each state will find it rational not to cooperate, and it will receive a higher payoff through defection. Consequently, even though both states have a common interest in achieving the CC outcome, acting individually, they will end up at the suboptimal DD outcome (Hasenclever, Mayer, and Rittberger 1997; see figure 1).

The Prisoner’s Dilemma therefore leads to a situation in which actors are worse off when they pursue their individually rational, self-interested strategy than they would be if they cooperated. The dilemma is derived from the analogy of two prisoners who have been arrested and accused of a crime but are detained and interrogated separately from one another. Their collectively optimal strategy is for both to confess (CC) and receive short prison sentences. But their individually optimal strategy is for each to deny his or her guilt and let the other one confess (CD or DC), in which case the denier walks free and the confessor receives a long sentence. This strategy leads both of them to deny guilt, and so they both end up with moderate prison sentences and therefore in a worse situation (DD) than they would have been in had they both confessed. Examples for which this analogy applies at the international level include the mitigation of climate change, attempts by the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) to maintain a quota on oil production, and attempts to negotiate disarmament treaties. In these cases, the incentives of the individual states to free-ride or cheat when acting in isolation will diverge from what would be collectively optimal for the group.

One of the key challenges for IR has therefore been to identify the conditions under which the Prisoner’s Dilemma can be overcome and global public goods can be provided through international cooperation. Regime theory, in particular, has attempted to identify the conditions under which international institutions may play this role. Various theoretical schools of IR have identified different ways in which the Prisoner’s Dilemma (collective action failure) may be overcome in relation to the provision of global public goods; mainstream IR has identified two: international institutions and hegemony.

Figure 1. Prisoner’s Dilemma. Number left (right) of comma refers to A’s (B’s) preference ordering (1 = worst outcome; 4 = best outcome). * indicates the equilibrium.

International institutions have been identified as the principal means through which collective action failure can be overcome. This is because they may enable states to take a longer-term perspective of their interests and thereby change their incentives to cooperate. The IR literature identifies three principal ways in which they can do this. First, institutions may create repeated interactions between states over time; so, instead of cooperation’s being based on a one-shot interaction, as the Prisoner’s Dilemma implies, institutions ensure that interaction is repeated over time (iterated). This reduces the incentives for a state to free-ride or defect because then it will forfeit potential longer-term gains. Second, institutions can provide information through surveillance that identifies free-riding states, thereby reducing the incentives to cheat. Third, institutions may play a role in reducing the transactions costs of cooperation. By institutionalizing the coordination of activities of states, cooperation becomes cheaper, and so the practical obstacles to cooperation are reduced (Axelrod 1984; Keohane 1982, 1984).

Hegemony has been suggested as a second means through which collective action failure can be overcome. According to hegemonic stability theorem (HST), the provision of a global public good depends on one state’s being powerful enough and willing to either provide the good unilaterally or coerce others into doing so (Gilpin 2001, 93–100; Keohane and Nye 1989, 44; Kindleberger 1973). Andreas Hasenclever, Peter Mayer, and Volker Rittberger (1997, 88–90) describe two circumstances in which a hegemon will provide an international public good when, otherwise, there would be collective action failure: the benevolent leadership model and the coercive leadership model. The first draws on the notion of the “exploitation of the big by the small” (Olson 1965, 29). That is, if the dominant power places a higher absolute valuation on the public good than the smaller powers do, it will provide that nonexcludable good irrespective of free-riding. In other words, its valuation of the public good will be so high that it will be prepared to bear a disproportionately high cost for its provision (Olson and Zeckhauser 1966). The coercive leadership model suggests that the hegemon will coercively induce the provision of the public good by others and so ensure its provision (Calleo 1987, 104).

In Suhrke’s account of the international politics of refugee protection, she is extremely skeptical about the prospects for overcoming collective action failure. For Suhrke, the absence of binding institutions relating to burden-sharing and the nonbinding nature of the global refugee regime make the prospects for overcoming collective action failure very limited. She argues that the only way in which a Prisoner’s Dilemma has historically been overcome and significant international cooperation has taken place in the refugee regime has been when a hegemon provided refugee protection. She suggests that the two examples of successful multilateral cooperation—refugee resettlement in Europe after the Second World War and the re-settlement of Vietnamese refugees after 1975—had their own underlying and, implicitly, realist logic—both depended on hegemonic power. In the first case, participating states shared a sense of values and obligation toward the victims of the war, creating an “instrumental-communitarian” interest in resettlement (Suhrke 1998, 413). Although not explicitly stated as such, this argument can be incorporated within the notion of benevolent leadership model. The United States, for example, unilaterally established the International Refugee Organization and resettled over 30 percent of the refugees; Australia and Israel were also major contributors. This high level of commitment, Suhrke argues, stemmed from the sufficiently high valuation by states of the need to provide protection that they were prepared to provide resettlement outside of an institutional framework, irrespective of the nonexcludability of the benefits. In the second case, Suhrke explicitly makes the case that coercive hegemony was required, with states’ needing “to be persuaded or pressured by the hegemon,” which was again the United States (1998, 413). Her argument, then, essentially reduces to the hypothesis that multilateral cooperation is possible only when either a benevolent or coercive hegemon is present (1998, 413).

Suhrke’s work sheds light on certain aspects of the international politics of refugee protection. Indeed, there are nonexcludable benefits that come from the provision of refugee protection and that encourage free-riding and burden-shirking, and hegemony has at times partly explained instances of burden-sha...