Chapter 1

PREACHING DIVERSITY IN BANDUNG

My experience among Bandung’s Muslims brought me into contact with several conceptions of oratory’s function and practice. On some points, all these understandings meet, sharing certain general assumptions. For example, all West Javanese Muslims would support the general proposition that Islamic oratory’s function is to communicate religious knowledge to Muslims (Arabic, tabligh), and to encourage them to implement these messages in their lives and the lives of their communities (Arabic, da‘wah). But the divergences encountered beneath that generalization are significant. Some people conceived Islamic oratory as a medium for learning and personal empowerment. A related conception sees oratorical communication as something that should enable listeners to develop the qualities expected of Indonesian citizens. In some settings it is considered that oratory instills in listeners dedication to activities such as employment and study. Another understanding singles out the cultivation of personal piety as the crucial element—repeated exposure to Islamic messages inculcates moral virtues. Another conception sees preaching as an affective experience that has the special power of drawing large numbers of listeners into community mosques for celebration and commemoration.

These diverse functions relate to contrasting visions of what Islam has to offer for Indonesian individuals and collectives, and they point to disparate Islamic movements and outlooks. In this chapter, I connect distinct conceptions of preaching with these movements, visions, and outlooks that combine in the present to make Bandung and West Java a diverse environment for Islamic listening.

The chapter is structured around four tables. Each table presents a cluster of terms, distinguished as a group because they form a distinct lexicon for naming oratory and conceiving its meanings and functions. I derived these clusters from my discussions with Muslims in Bandung, from my observations at preaching events, from normative writings about oratory, from historical writings on Islam in West Java, and from programmatic statements of various groups that hold preaching events. Each cluster (other than the first) represents a moment of innovation or renewal, meaning a historically specific point of change at which this or that conception of oratory was foregrounded as superior to other conceptions. These moments of innovation should not be interpreted as forming a chronological sequence in which one conception succeeds the previous one, and neither do they designate four distinct currents of preaching activity. West Java is a complex, diversified society where audiences prefer a wide range of preaching styles, old and new. Furthermore, preachers tend to look sideways across borders between audiences, and the emergence of new styles often leads them to adapt and appropriate novel elements into their own style. To use a term from James Hoesterey (2012, 54), preachers “recalibrate” their styles in response to new possibilities. In this way, preaching novelties circulate beyond their originating contexts and blend into existing styles.

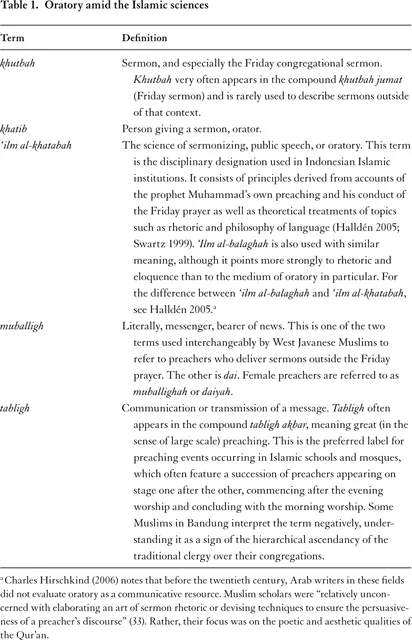

Most of the lexical items in the tables that follow are loanwords from Arabic. I present them here in their Indonesianized forms. If a term is not of Arabic origin, I indicate its linguistic origin in brackets.

Unlike the terms appearing in tables 2, 3 and 4, the terms in table 1 cannot be tied to any specific moment. Rather, they denote one of the many branches of the Islamic sciences to have emerged since the time of the Prophet (Halldén 2005; Swartz 1999). Their use is relatively stable and persistent, as they constitute the technical vocabulary used in the discipline’s scientific literature, in its hierarchies of expertise, and in the institutions that provide courses in predication such as the Faculty of Dakwah and Communication and some of Indonesia’s many Islamic schools.

The stipulations cultivated within this discipline are publicly visible in the formalities of the ritual order and conduct of oratory, especially in the Friday sermon, where they are understood as continuations of the Prophet’s own practice.1 In non-khutbah preaching, these formalities can be seen and heard at the opening of sermons. The opening utterances, which typically take approximately one minute to verbalize, include all or some of the following: a statement that all praise belongs to Allah (Arabic, tahmid); a statement of the Muslim creed (Arabic, tashahhud); and a request for Allah to bless the Prophet Muhammad, his family, and other notables (Arabic, salawat). Oratory’s formalities are given heightened importance in competitions. The oratory component of Indonesia’s Islamic competition, the Musabaqah Tilawat Al-Qur’an (MTQ: Competition in Qur’anic Recitation), is known as the Musabaqah Syarh Al-Qur’an (Competition in Qur’anic Declamation). Teams of three compete in this event. One team member recites a passage from the Qur’an, her colleague translates it poetically, and the third member, the muballigh, provides an oratorical interpretation. The contributions of all three are evaluated by judges. In the oratory phase, judges pay close attention to, among other things, the correct pronunciation of introductory invocations, blessings, and formulas.

The preachers encountered in the pages of this book, however, are career orators. A preaching career depends on repeat invitations, and these are not issued based on an orator’s ability to reproduce the formal aspects of oratory. Bandung audiences expect much more of skillful preachers than that. Preachers succeed through their ability to mediate Islam with speech appropriate to context and to maintain audience attention to their speaking. Outside the Friday collective prayer, therefore, orations are more strongly shaped by embodied sociability than by formal norms. Nevertheless, Muslims in some segments of Bandung’s Islamic society insist that oratory should reflect the stipulations found in fiqh (normative guidelines extracted from revelation and the Prophet’s example). The guidelines constraining preaching are referred to as adab al-da‘wah (Arabic, preaching etiquette). This code extends beyond the formal norms affecting ritual order and decorum, providing stipulations concerning the conduct and character of the preacher and evaluating the virtuousness of preachers’ behavior on and off the preaching stage (see Hirschkind 2006, 130–37). In chapter 3, PERSIS’s fiqh-based deliberations about Islamic communication are discussed. These problematize an excessive reliance on communicative skill and performance ability.

My final words on this group of terms concern competency. In some spaces of Islamic West Java there is a deeply held belief that a competent preacher should be an expert in the Islamic sciences. In other words, a person is qualified to preach if they belong to the learned class of Muslim leaders known as kyai in Java, ajengan in West Java, and tuan guru in Sumatra and Lombok.2 In academic as well as popular representations, they are acknowledged as bearers of Islamic knowledge, who by necessity possess verbal communication skills in order to fulfill their roles as community leaders. Writing in the late 1950s, Clifford Geertz characterized this class as “cultural brokers” mediating both Islamic authority and postindependence modernity to Indonesia’s Islamic communities. These men were “specialists in the communication of Islam to the mass of the peasantry” (Geertz 1960, 230). Although the archetype still bears enormous authority among listeners, especially in rural areas, contemporary preaching competencies suggest something different. Indonesians mostly enjoy preaching delivered by a class of Muslims who have received some training in the Islamic sciences and who generally self-represent in the form of kyai but whose basic capital lies in their skill in verbal performance.3 Since Geertz presented his understanding, this class of specialists has flourished in forms and styles he could not have foreseen. He could not foresee, for example, the highly popular broadcasts of child preachers in reality television programs or the technologically sophisticated spirituality training popular in corporate environments (Rudnyckyj 2010). As I comment below in more detail, in contemporary Indonesia, muballigh rely on a broader range of skills in communication and performance than is encountered among the kyai/ajengan.4

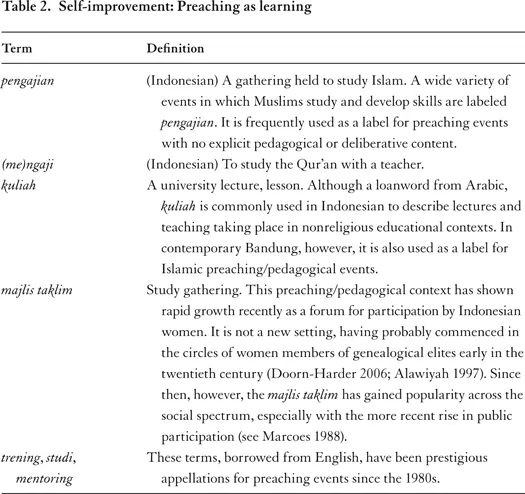

Many Muslims prefer the terms in table 2 over those in table 1 as labels for describing preaching events. The preference for these terms has emerged as Indonesians have progressively come to value processes of individual learning more highly than “mere” listening. The value of Islamic education as an individual and social good became particularly apparent in two specific moments of change. In the early twentieth century, Islamic groups with reformist or modernizing programs made the acquisition of Islamic knowledge a priority for individual Muslims, partly because of an egalitarian view of Islamic knowledge that took issue with the mediating role of the clerical elites. According to this view, Islam was a straightforward religion capable of being understood by all Muslims. Reformist groups such as PERSIS and Muhammadiyah promoted this principle and, in doing so, identified themselves as modern through their insistence that reflection and critical thinking were capabilities that all humans should attempt to cultivate.

The second moment was the epochal changes occurring after Indonesian independence. Mass education was among the highest priorities of the Sukarno governments (1945–66) as well as the New Order government that followed (1966–98). Dale Eickelman’s (1992, 1998) account of coeval changes in the Arab world emphasizes the implications of these events for Islamic practice: widespread literacy increased Muslims’ access to religious learning outside entrenched elites and stimulated the emergence of publications and media for new classes of readers. In conjunction with the uptake of mass communications technologies, literacy enabled the emergence of new styles of Islamic authority. These changes provide the background for the more recent phenomenon commonly described as the kebangkitan Islam (Islamic Resurgence). By the 1990s individualized projects of Qur’anic study and performance were so popular that anthropologist Anna Gade described them as “a new kind of educational movement that was sweeping Indonesia” (2004, 21). These movements idealized an individualized subjectivity that could be empowered through study; compared with this idealization, the collective implications of the earlier terms made them unattractive.

Bandung has been the location for projects that projected these novel understandings of Islamic learning (Rosyad 2006). The Salman/ITB movement, which caught national attention in the 1970s, was the most significant of these for its pioneering of new Islamic learning styles. Its intellectual leader was Imaduddin Abdulrahim (1931–2008), whose experience in the global Muslim student movement had given him knowledge of the Islamic education programs of organizations such as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. As a faculty member of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), he oversaw the development of novel programs in the institute’s mosque, known as Salman. Indonesian students were beginning to embrace an Islamic social identity and attended the programs in large numbers. The Salman movement’s programs, in their appellations as well as substance, implied that Indonesian Muslims were individuals with potential to be developed for the benefit of the nation and that Islam provided the tools and motivations for this development. In accordance with this understanding, Salman followers were encouraged to engage positively with technology and science and to consider these as forming an integral part of Islamic revelation (Abdulrahim 2002, 70–104). Its programs, which spread throughout Indonesia through Salman’s caderization program, were given English titles such as “mental training,” “dakwah management,” “mentoring,” and “intensive study” (Rosyad 2006). This was not the audience for the traditional kyai, who relied on recognition of his scholarly authority as the bedrock of his competence. Salman/ITB programs resembled communications between equals rather than virtuoso displays by privileged mediators.

The Salman programs created waves even for Muslims not attracted to them because preaching events that did not have learning as their substantive aim were recalibrated as learning experiences. In some settings, the processes of relabeling are striking. The privately owned educational institution known as Siraman Iman (A Sprinkling of Faith), discussed in chapter 3, provides pay-for-entry Islamic instruction to wealthy residents of Bandung and is overwhelmingly patronized by women. Its premises are described as a “campus,” and its programs are advertised with names such as intensive Islamic study (kajian Islam intensif), day classes (kelas siang), and training (trening). These events are thick with the trappings of contemporary pedagogical styles such as whiteboards, overhead projectors, and printed study materials. These trappings are clearly important tools that enable the institution to present itself as a center for serious study, but the success of the program I attended relied on the brilliant skills of the institute’s orators. The presenter gave a compelling, energetic, and stimulating preaching performance to an audience for whom the word pengajian is more palatable than tabligh. This example not only signals the instability of the labels used for naming and promoting preaching events. It also demonstrates how oratory retains its value for Bandung Muslims. Siraman Iman packages oratorical skill in forms suitable to a specific niche of the Bandung community.

“Dakwah” is the label given to the pronounced surges of Islam into the public sphere occurring since the 1960s (table 3). The movement includes programs of Islamically informed change that implied differing meanings for contrasting Islamic segments.5 For social scientists, dakwah was an umbrella theme for Islamically based projects of political and social development as well as a framework for dealing with social change that appeared to threaten the fabric of Indonesian society. For the government, it became a legitimizing tag for development goals. For politically oriented activists, it was a movement for bolstering Islam’s presence in social life and the political sphere, ideally by working in partnership with a similarly committed government. For unspecialized dakwah audiences, the increasing volume and frequency of Islamic messages meant a broadening range of cultural forms for experiencing them.

The dakwah moment brought oratorical practice into the critical spotlight and gave rise to two incompatible trajectories. On the one hand, the forms for expressing and participating in Islam expanded in number and became more accessible; on the other, the conception of dakwah as a motivation for serious programs of reform and transformation gathered strength. These two...