CHAPTER 1

The Hegelian Bacillus

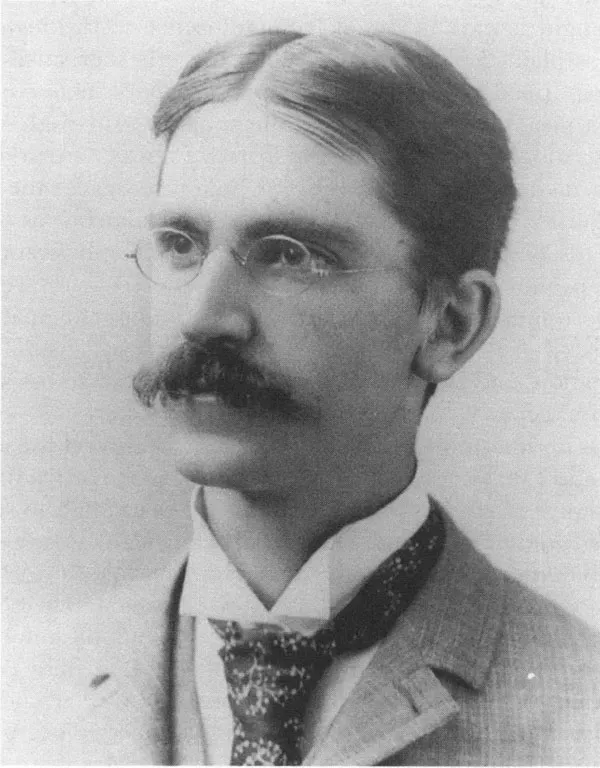

SOON after John Dewey arrived at Johns Hopkins to begin his graduate studies in philosophy, President Gilman tried to persuade him to switch to another field. The bulk of the university’s resources were committed to the natural sciences, and Gilman regarded philosophy as an insufficiently scientific discipline that remained too closely tied to religious perspectives hostile to the development of scientific knowledge. Hence, the philosophy department was one of the weakest in the university. No full professor had been appointed in the field, and teaching duties were handled by three young lecturers: G. Stanley Hall, George Sylvester Morris, and Charles Sanders Peirce. Dewey, however, was not persuaded by Gilman’s arguments, and he quickly gravitated to Morris, the least scientific of Hopkins’s trio of philosophers and a neo-Hegelian.1

Morris’s presence at Hopkins was symptomatic of the growing influence of post-Kantian idealism on American philosophy. A few months before Dewey arrived in Baltimore, William James had filed a brief in the British journal Mind against the growing popularity of Hegelianism in the English-speaking world. “We are just now witnessing a singular phenomenon in British and American philosophy,” he observed. “Hegelism so defunct on its native soil … has found among us so zealous and able a set of propagandists that today it may really be reckoned one of the most powerful influences of the time in the higher walks of thought.” While (after a brief flirtation with materialism) German philosophers rushed “back to Kant,” British philosophers led by T. H. Green and F. H. Bradley at Oxford and Edward and John Caird in Scotland had turned to Hegel for support as they worked out a domestic brand of absolute idealism with which to challenge the long-standing dominance of the empirical tradition of Locke, Hume, Bentham, Mill, and Spencer. In the United States, Hegel clubs had sprouted up throughout the country, and in St. Louis an energetic band of Hegelians led by William Torrey Harris had successfully launched the nation’s first professional journal of philosophy, the Journal of Speculative Philosophy. In addition, absolute idealists including Morris, George H. Palmer, and Josiah Royce had established a foothold in the philosophy departments of leading American universities. These, James felt, were lamentable developments, for “Hegel’s philosophy mingles mountain-loads of corruption with its scanty merits.” Comparing the spell of absolute idealism to nitrous-oxide intoxication, James hoped he might show “some chance youthful disciple that there is another point of view in philosophy.”2

Dewey may have read James’s article, but if so, it had little effect. By the end of his first term at Johns Hopkins he was already committed to “a theory which admits the constitutive power of Thought, as itself ultimate Being, determining objects.” For him, Hegel’s thought was intoxicating; it “supplied a demand for unification that was doubtless an intense emotional craving, and yet was a hunger that only an intellectualized subject-matter could satisfy.” He held this commitment to Hegelianism firmly for about ten years; it waned slowly for nearly another decade, and Dewey never completely shook Hegel out of his system. He remarked in 1945, “I jumped through Hegel, I should say, not just out of him. I took some of the hoop … with me, and also carried away considerable of the paper the hoop was filled with.”3

This remark applies as much, if not more, to Dewey’s social theory as to other aspects of his philosophy, despite the fact that in his earliest years as a philosopher he devoted relatively little attention to social theory as such. Social and political concerns had little to do with his conversion to absolute idealism, and it was not until the late 1880s that he took much interest in democratic theory or politics. Before this, he centered his attention on more abstruse metaphysical issues and on the threat of experimental psychology to religious faith, believing that the problem of philosophy was one of determining “the meaning of Thought, Nature, and God, and the relations of one to another.” But if the problems of democracy had little to do with Dewey’s initial attraction to absolute idealism, it is of no small significance that he was an absolute idealist when he began to address these problems, for his early democratic theory was as thoroughly infected as his previous work in metaphysics and psychology with what he later lightly termed the “Hegelian bacillus.” Thus it is important to explain why this bacillus found in Dewey such a willing host.4

ORGANIC IDEALISM

Many years after he left Vermont, Dewey remarked that the “intuitional philosophy” he learned from Torrey “did not go deep, and in no way did it satisfy what I was dimly reaching for.” The evidence that remains from this early period of his career bears him out. The two articles he wrote before graduate school on the metaphysics of materialism and on Spinoza’s pantheism are often said to be evidence of an initial intuitionist perspective, but it is difficult to determine from these essays what Dewey’s metaphysics were at the time. The critique of the materialists and Spinoza in these articles was strictly logical. In each case Dewey pointed to contradictions in the reasoning of exponents of the offending doctrines, but in neither instance were his own metaphysical convictions readily apparent. Dewey was looking for a philosophy that would free him from the guilt-ridden pietism of his mother, satisfy his hunger for unification, and provide a rational underpinning for the feeling of oneness with the universe which he had experienced in Oil City, but Torrey’s intuitionism with its sharp dualisms and question-begging leap of faith could not do so. Without a metaphysics that could meet his emotional and intellectual needs, philosophy was for Dewey little more than an “intellectual gymnastic.”5

At Hopkins, Dewey found in George Morris a teacher who had suffered an “inward laceration” similar to his own and discovered in British neo-Hegelianism a cure for the alienation that beset them both. Born in Norwich, Vermont, in 1840, Morris had attended Dartmouth College and Union Theological Seminary, where he studied with Henry Boynton Smith, a leading American theologian. Impressed by Morris’s abilities as a scholar, Smith urged him to undertake advanced study in Germany and pursue a career in philosophy rather than the ministry. Morris departed for Europe in 1866 and took up his studies in Germany with Hermann Ulrici of Halle and Friedrich Trendelenburg of Berlin. In the short run, he was ill served by this higher education. His fiancée broke off their engagement because “he had grown so learned and changed so much in his religious opinions that she was afraid of him,” and he returned home in 1868 to find that there were no jobs in American colleges for philosophers who had drunk too deeply of the waters of German learning. After a few years spent as tutor to the children of a wealthy New York banker, Morris finally landed a job in 1870 as a professor of modern languages and literature at the University of Michigan, where the chair in philosophy was held by a Methodist minister who had dropped out of school at the age of thirteen.6

The early 1870s were also a trying period for Morris intellectually as he wrestled with the challenge of Darwinian science to religious faith and the alienating dualisms meeting this challenge seemed to entail—the same dualisms of self and world, soul and body, God and nature which troubled Dewey. He captured this alienation in a striking metaphor in an 1876 essay, “The Immortality of the Human Soul”: “The water-spider provides for its respiration and life beneath the surface of the water by spinning around itself an envelope large enough to contain the air it needs. So we have need, while walking through the thick and often polluted moral atmosphere of this lower world, where seeming life is too frequently inward death, to maintain around ourselves the purer atmosphere of a higher faith.” For some, writing off the natural world in this fashion was a satisfactory resolution of the tensions between science and religion, but Morris could not free himself from the force of his teacher Trendelenburg’s contention that “thought is suffocated and withers without the air and light of the sensible cognition of the world of real things.” As a consequence, the atmosphere inside his envelope of faith grew steadily staler.7

By the end of the decade Morris’s life had brightened considerably. In 1877 he was invited to lecture in philosophy for a semester at Johns Hopkins, and he subsequently negotiated a regular arrangement whereby he taught philosophy for one semester each year at both Hopkins and Michigan. About the same time Morris discovered in the work of T. H. Green and the other British idealists a philosophy that dissolved the dualisms that had tormented him and a metaphysics that convinced him that nature was not a polluted moral atmosphere but rather the manifestation of divine spirit.

Beginning with Green’s long, destructive introduction to a new edition of Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature published in 1874, the idealists had launched an effort to reconcile religion and Victorian natural science by means of a critique of the agnostic, empiricist epistemology that Herbert Spencer and others contended was the philosophical ally of scientific investigation. Rather than shrink from or deny the accomplishments of natural science or attempt to establish separate spheres of authority for faith and reason as Morris had done, the idealists met science head on and argued that the very successes that natural science could claim in making sense of the world were inexplicable in terms of empiricist epistemology and were explicable only in terms of the metaphysics of objective idealism. As Dewey said, the neo-Hegelians were attempting “to show that there is a spiritual principle at the root of ordinary experience and science, as well as at the basis of ethics and religion; to show, negatively, that whatever weakens the supremacy and primacy of the spiritual principle makes science impossible, and positively, to show that any fair analysis of the conditions of science will show certain ideas, principles, or catagories—call them what you will—that are not physical and sensible, but intellectual and metaphysical.”8

Empiricists and idealists agreed that science was the knowledge of relations between things, but, the idealists argued, empiricism with its theory of knowledge as the impression of discrete sensations on a passive mind was unable to explain how such relations are known. Insofar as they ordered sensations, these relations could not be the product of sensations, for that view would be akin to a geologist’s teaching that “the first formation of rocks was the product of all layers built upon it.” Thus the empiricists had to admit that ordinary experience as well as scientific knowledge presupposed a constructive function for consciousness which their epistemology did not allow. Far from being the ally of science, empiricism rendered science impossible. “A consistent sensationalism,” Green observed, “would be speechless.”

This much Kant had shown. The idealists advanced beyond Kant by means of their (controversial) theory of internal relations. This theory held that all the relations of a particular thing were “internal” to it, that is, they were all essential characteristics of that thing. Knowledge of any particular thing thus rested on knowledge of a connected whole of which it was a part, and the fact that all the relations of every particular thing were essential implied “the existence of a single, permanent, and all-inclusive system of relations.” Moreover, because relations were the product of consciousness, there was further implied the existence of “a permanent single consciousness which forms the bond of relations.” This logic showed, at least to the satisfaction of Dewey, Morris, and other idealists, that “in the existence of knowable fact, in the existence of that which we call reality, there is necessarily implied an intelligence which is one, self-distinguishing and not subject to the conditions of space and time.” This eternal self-consciousness was the idealists’ God. Only this God, the Absolute, could know reality in its totality, but because eternal intelligence was partially and gradually reproducing itself in human experience man could share in this knowledge through science. Science was “simply orderly experience. It is the working out of the relations, the laws, implied in experience, but not visible upon its surface. It is a more adequate reproduction of the relations by which the eternal self-consciousness constitutes both nature and our understandings.” As such, science posed no threat to religion, for it presupposed “a principle which transcends nature, a principle which is spiritual.”9

This “metaphysical analysis of science” released Morris from the doldrums in which he had been mired since his return from Europe, and by the time Dewey arrived at Hopkins, he was in the midst of an enormously productive decade of scholarship which established him as one of the foremost American philosophers. Dewey succinctly summed up Morris’s variant of neo-Hegelianism, which might best be termed “organic idealism,” in a letter to Torrey in the fall of 1882:

Prof. Morris … is a pronounced idealist and we have already heard of the “universal self.” He says that idealism (substantial idealism as opposed to subjectivistic or agnosticism) is the only positive phil. that has or can exist. His whole position is here, as I understand it. Two starting points can be taken—one regards subject & object as in mechanical relation, relations in and of space & time, & the process of knowledge is simply impact of the object upon the subject with resulting sensation or impression. This is its position as science of knowing. As science of being, since nothing exists for the subject except these impressions or states, nothing can be known of real being, and the result is skepticism, or subj. idealism, or agnosticism. The other, instead of beginning with a presupposition regarding subj. & object & their relation, takes the facts & endeavors to explain them—that is to show what is necessarily involved in knowledge, and results in the conclusion that subject and object are in organic relation, neither having reality apart from the other. Being is within consciousness. And the result on the side of science of Being is substantial idealism—science as opposed to nescience. Knowing is self-knowing, & all consciousness is conditioned upon self-consciousness.10

Torrey might well have been disturbed by this letter. Although he ack...