Chapter 1

Building Effective Bureaucracies and Promoting Democracy in Kosovo

Dardan Velija (2008), a former senior government official, likes to tell an anecdote about how Kosovo traffic police officers stopped him twice for speeding. The officer stopped the car, politely asked for the driver’s documentation, and then ordered him to pay the fine for driving above the speed limit. The police officer fined Velija even though he had noticed the VIP sticker on the front window of Velija’s car that signaled the driver’s important government position. Velija, a political adviser to the Kosovo prime minister, had to pay a fine just like any other citizen. “In Albania,” he added, “the police would not even stop me because they would notice the Kosovo VIP sign in the car.” Indeed, in Southeast Europe, police officers are notorious both for getting bribes from normal citizens and for not “touching” senior state officials. For example, in Serbia, police officers were considered the most corrupt public officials according to a 2008 poll (Gallup 2008, 22).

I was puzzled by the professionalism and ethics of the police force in postwar Kosovo. Police forces in postwar countries tend to be corrupt and repressive. Yet I heard that Kosovo police officers talk about observing human rights and protecting the dignity of civilians. Local police officers would speak about the importance of international organizations in recruiting and training officers. During my dissertation fieldwork in 2008, I expected to see that international organizations would fail to build state institutions that would protect individuals as well enlarge their freedoms. International actors not only would fail to build local institutions, but in fact would undermine them. But as I gathered data about Kosovo’s police force and other institutions, I found that I was wrong.

Can ambitious international interventions build states and democracies?1 The proliferation of internal wars since the end of the Cold War has led international actors to carry out one of the biggest and most challenging “experiments” in international politics: participating actively in rebuilding states and societies (Paris and Sisk 2009, 1–2).2 However, the US military’s interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, among others, have made the enterprise of external state building and democracy assistance controversial. Scholars and pundits who focus on the difficulties associated with building state bureaucracies and democracy in these two cases caution against carrying out such expensive, complex, and potentially ineffective interventions in the future (Brownlee 2007, 315, 339; Edelstein 2009, 51). Yet the proliferation of guidelines on how to build state capacity and democracy after a war indicates the continuing interest that international organizations have in this area.3 This is because ample research indicates that effective state bureaucracies and democratic institutions make possible better life chances for individuals and societies, help prevent civil war and terrorism (Fearon and Laitin 2004; Krasner 2004) as well as failed states (Bates 2008; Fund for Peace 2013; Ghani and Lockhart 2008; Rotberg 2004), and promote development (Keefer 2004).

Much of the literature assessing state capacity and the success of international interventions in building states and democratic orders focuses on either one or the other mission (and sometimes conflates the two) or, if analyzing the state in particular, treats it as a single entity.4 Such a unitary conception of “stateness” can be overly abstract and fails to distinguish between state bureaucracies that vary in their effectiveness. This analysis is different. I unpack the state into its core bureaucracies—that is, the police force, customs service, central administration,5 and the court system.6 By opening the “black box” of the state and analyzing its constituent core bureaucracies, we can explore analytical differences in bureaucratic effectiveness that are crucial for understanding how political actors can build states that are able to provide relevant public goods to their populations. In addition, I analyze both state building and democratization as I examine whether various factors can engender bureaucratic effectiveness and democratic progress.

This study challenges the prevailing belief that international actors should use the same strategies to build effective bureaucracies that they use to build democracy. I find that while effective bureaucracies are most likely to materialize when international organizations insulate public administrators from political and societal influences, democracy is enhanced through international support of public participation and contestation. Therefore, in clientelist contexts, democratization and state building are two different processes that require complementary approaches by international organizations, especially in the short term. In the long term, properly built democratic domestic constituencies, such as civil society and the media, are necessary to sustain the effectiveness of the bureaucracy.

I develop this argument through a Weberian analysis that places emphasis on bureaucratic organizations that are insulated from political pressures through impartial rules of recruitment and advancement (Weber 1954, xxxix–xliii). Bureaucracies thrive when they are sufficiently autonomous from social demands, as they create disinterested routines and implement policies in an impartial manner. International insulation from political and societal influence refers to effective control by international actors of local bureaucracies for an extended period of time. The prevalence of patronage networks in Kosovo at the time of international intervention meant that administration jobs could have been given to loyal followers of political parties when state bureaucracies were transferred early to the authority of elected politicians, in the local ownership approach.

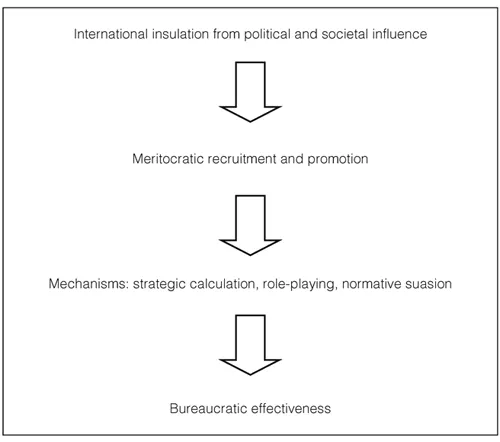

Various mechanisms, including strategic calculation and role-playing, contributed to the creation of the effective bureaucracies in Kosovo. This argument for the construction of effective bureaucracies is stylized in figure 1.1.

The crucial factor that linked international insulation to bureaucratic effectiveness was meritocratic recruitment and promotion. Without meritocratic recruitment and promotion, the mechanisms of strategic calculation and role-playing led to clientelist bureaucracies that were steeped in corruption and ineffectiveness. In the effective bureaucracies, international administrators stayed in the boards that recruited and promoted according to merit. In addition, international administrators inserted bureaucratic rules that motivated performance and penalized corruption. Public officials learned that they were being evaluated and promoted on the basis of their performance. In Kosovo, when international organizations structured the rules of new bureaucracies while insulating them from political, clientelist pressures, such institutions attracted and retained professional domestic employees, who then performed their tasks more effectively. Such bureaucratic measures included testing and vetting for initial recruitment into the bureaucratic organization, periodic performance evaluations, and awarding of advancement based on work performance.

Figure 1.1. Mechanisms of socialization in effective state bureaucracies.

The new employees in the professional bureaucracies learned that success depended upon following rule-bound behavior. Strategic calculation by local employees was therefore another mechanism that contributed to their success, because self-interest in the effective bureaucracies became constructed as following rule-bound behavior. The new recruits in these bureaucracies learned that they could advance in the organization by following impartial procedures; if they did not, they would be demoted or even fired. They therefore feared the penalties for inadequate performance or unethical behavior.

However, the system of oversight and penalization for self-interested employers was not enough to ensure their efficient behavior. Through another mechanism of role-playing (Checkel 2005, 810–12), the bureaucrats followed cues and shortcuts to enact particular organizational roles. When role-playing, individuals were not simply calculating the costs and benefits of their actions, because they were boundedly rational agents who follow organizational cues. The final mechanism of normative suasion (Checkel 2005, 812–13) occurs when social agents are open to the redefinition of their interests and preferences as they persuade each other. Instead of calculating strategically or following organizational cues, employees complied with the rules because it was the appropriate thing to do.

In addition to state building, another goal of international intervention was to support democratization. In the case of Kosovo, democratic progress after the intervention was enhanced by a coalition of international actors and mobilized ordinary citizens. The main nationalist party in Kosovo strategically appealed to the international community by framing its movement as “democratic” in order to gain international support. Nationalists built their legitimacy through elections and public mobilization around the national cause. However, when previously mobilized people were marginalized, democracy was compromised as voters found it difficult to hold politicians accountable. Nationalist demobilization refers to the elite’s use of the nationalist project to silence, marginalize, and exclude previously mobilized citizens, and thereby prevent social and economic issues from entering the public agenda (Gagnon 2004, xx–xxi). Hence, democracy was enhanced through international support of domestically mobilized citizens. However, when international actors supported the demobilization of the public, they undermined democracy.

I turn now to a critical examination of the existing literatures on state building and democratization, which provide the theoretical anchor for this study. Following this review, I turn to methodological issues in this thesis: case selection, approach, and key concepts and their measurement. I conclude with an overview of future chapters.

State-Building Hypotheses

International interventions that aim to build states are highly controversial among scholars (Brownlee 2007, 315, 339; Knaus and Martin 2003). Some scholars question the motivations of international actors because they see parallels between current state-building efforts and previous failed attempts by European colonizers to build states and societies on the global periphery (Chandler 2006; Easterly 2006, 269–310). Other scholars claim that the impact of colonizers was not uniformly negative but depended on the colonizer and local conditions (Kohli 2004; Rothermund 2010). Current state-building efforts are similar to earlier colonial enterprises because both are applications of Western models to non-Western cases. Unlike the European colonies of the nineteenth century, however, the contemporary liberal international interveners aim to stay for only a limited time and leave quickly after they have achieved their goal of stability (Dobbins 2008, xvii–xix).

The rate of success of modern state-building efforts has also been mixed, if we use the resurgence of civil war as an indicator. Because the goal of building state institutions after war is assumed to be a precondition for building a sustainable peace, a resurgence of civil wars undermines this claim. Madhav Joshi and T. David Mason (2011, 389) estimate that 48 percent of the 125 civil wars that occurred in seventy-one countries between 1945 and 2005 resurged again. Most of the countries have not resorted to war after the intervention, but the missions have often had more ambitious goals, such as democracy and effective state bureaucracies. Therefore, several scholars and practitioners argue that the international state-building missions have not been successful in East Timor (Chopra 2002), Bosnia (Chandler 2000), and Kosovo (King and Mason 2006). For instance, the resurgence of armed fighting in East Timor in 2006 was a shocking reminder that the new state was not the peace-building success that the United Nations (UN) had advertised.

Scholars have also contested the purported success stories of earlier examples of state building. The RAND Corporation’s policy studies on state building (referred to as “nation building”) claim that Germany and Japan are clear cases of successful American interventions that built democratic institutions and functioning state bureaucracies (Dobbins 2003, xix–xxii). However, the positive impact of these interventions is unclear because these countries already had functional state institutions (Brownlee 2007, 323–24; Shefter 1994, 36–45; Cooley 2005, 145). Historical legacies of state formation matter in the current configuration of democratic institutions and state bureaucracies. If state bureaucracies could adequately implement their policies before the war, and their prewar personnel continued working in the administration, then this legacy explains at least part of current state capacity.

What may explain the variation in effectiveness among the different state bureaucracies? First, we may posit that the higher the extent of local ownership of domestic bureaucracies, the higher the capacity of the bureaucracy to provide public goods (Evans 2004; Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti 1993; Weinstein 2005). The expectation is that the assumed one-size-fits-all approach of international actors does not work well across different contexts. Local ownership works through various mechanisms. First, local stakeholders, due to their superior knowledge of local conditions, know their priorities and can define their solutions better than the international bureaucrats (Scott 1998, 6, 316–19; Pickering 2007; Skendaj 2009, 65–66, 75). The development literature also points to the importance of local knowledge for needs assessment and participation (Chambers 1997). Second, according to a former practitioner and now critic of international organizations, William Easterly, local knowledge matters because of the mechanisms of feedback and accountability. Feedback from local people ensures that their needs, and not international priorities, are answered. In democracies, local people also hold their elected leaders accountable through elections, but they have little or no power over international actors (Easterly 2006, 269–310).

The concept of local ownership is best understood as varying along a continuum. At one end, in the absence of local ownership, international organizations set the agenda, make the rules for the institutions, and run the institutions without the collaboration of local stakeholders, such as politicians, bureaucrats, or the public. At the other end, full local ownership occurs when local leaders set the agenda and build the institution according to their own priorities. Scholars who support full and immediate “local ownership” assume that the country has endogenous resources to devote to the process (e.g., Chandler 2002; Weinstein 2005). However, this expectation is belied by the high number of failed states in the international system—35 out of 194 states, according to one calculation (Fund for Peace 2013).

A lack of local knowledge about and sensitivity to the local context also explains the difficulties that international organizations face when they attempt to build democracy and state bureaucracies. Various authors claim that such distance from the local context undermines the work of international state builders and democracy promoters (Gagnon 2002; Pickering 2007). Their assumption is that only local people can know the context and the power structures.

By contrast, statist theories of bureaucracy emphasize that any measure that enhances the insulation of the bureaucracy from societal pressures increases its performance (Weber 1954, xxxix–xliii, 40; Bensel 1990, 94–237; Evans 1995; Geddes 1994). Thus, meritocratic recruitment and professional socialization within state bureaucracies are posited to enhance state building. Applying this hypothesis to international interventions, I expect that bureaucracies will perform better when international actors take measures to insulate central state bureaucracies from societal influence.

What is the relationship between democratization and state building? Consolidated democracies in the modern world possess effective bureaucracies that are able to implement their goals and provide high-quality services to their citizens. Modernization theorists argue that the now-successful polities in Western Europe went through a sequence of political developments: first, centralized state power was consolidated over the territory and the people; second, bureaucratic structures were differentiated and specialized; and third and finally, popular participation was secured through mass-based parties. Samuel Huntington considered this sequence important because the reverse sequence of political participation before state centralization and bureaucratic specialization undermined a strong central government in the United States (Huntington 1968). Roland Paris (2004) also argues for the construction of state institutions before holding elections. The implication of this argument is that the promotion of democracy should occur after the consolidation of central state bureaucracies.

Other scholars, however, see democracy as a precursor to state performance. The representative theory of democracy expects that democratic institutions such as citizen participation and electoral contestation lead to a more effective provision of public goods such as education (Dahl 1971) and food security (Sen 1999a). The state administration will have a greater capacity to plan and enforce its policies if citizens hold their leaders accountable. Multiple mechanisms link democracy to bureaucratic effective...