Chapter 1

Labor Markets and Class Politics

The most distinctive quality of the political economies of the Gulf rentiers is their extraordinary labor markets. In the extreme rentiers of the Gulf, the vast majority of citizens who work for a wage work in the public sector for high wages set largely by government edict. Foreigners work in the private sector (or sometimes in the public sector) for wages set by the market. These labor markets have profound political consequences, especially on the class politics of citizen society.

The three extreme rentier states of the Gulf— Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar— have built elaborate welfare states that include free health care, free education through university, marriage grants, subsidized utilities, and sizable housing grants (or interest-free loans). Taken together, these programs are generous, there can be no doubt. But by and large they do not put cash directly into the pockets of citizens. To do this, the state gives citizens public-sector jobs (or private-sector jobs with paychecks subsidized by the state). As a consequence, public-sector employment in the rich rentiers has an uncomfortable dual nature. In one sense, public-sector jobs are a standard exchange of labor for pay; in another, many citizens see these jobs as their monthly payments from what amounts to the national oil trust fund. As a Kuwaiti researcher put it, “[f]or the ruling family, the bureaucracy serves as a respectable, and apparently modern means of distributing part of the ‘loot’, which replaces the traditional method of straightforward handouts.… The creation of new jobs in the bureaucracy became an objective in its own right, with little regard to what new appointees should or could do.” In this light, generous pay for little labor is not a violation of market rationality—or featherbedding—but, instead, a birthright of citizenship. This point is critical to understanding the political economy of Gulf labor markets and Gulf politics.

In Kuwait, the process of distributing state jobs is highly centralized. Citizens register their names with the Civil Service Commission (CSC), which has a web-site for this purpose. After a wait of some time, the CSC nominates most of those who apply for positions in the public sector. Local newspapers publish lists of those who receive employment in state offices and the office to which they have been appointed. This centralized system was put in place to increase transparency and to discourage favoritism. The tradition of more or less guaranteeing a state job to every graduate, however, goes back to the 1960s. Published reports indicate that most of those who apply for a job are offered one; from the inception of the system in 1999 to the end of 2006, some 98,000 eligible Kuwaiti citizens applied for and 78,000 received positions. More detailed figures on who did and did not receive positions (from 1999 to 2003) reveal that all but a few hundred of those who did not receive a position were women with a high school education or less. Almost all women with college degrees and men with secondary school degrees and higher received a position. Citizens can register their names again if they leave state employment or are released as being “unsuited” for their original appointment. The other two extreme rentiers—Qatar and the UAE—similarly give a public-sector job to most citizens who want one. The Qatari state provides an implicit guarantee of a position in the public sector to secondary school and university graduates.

The number of new state employees is driven by the number of new graduates rather than by any demand for additional employees on the part of the state bureaucracy. Thus, many employees have very little to do. There is a great deal of what in the Gulf is called “masked unemployment” (al-batala al-muqanna‘a), by which is meant the existence of positions filled by occupants who do no productive work—that is, featherbedding. The phenomenon is not new—the Kuwaiti parliament undertook its first investigation of the problem in 1963. Stories circulate in Kuwait about new employees showing up for a new job and finding neither any work to do nor a desk to do it from.

Working conditions in the public sector are hardly onerous. In Kuwait, government employees are typically expected to be at work seven hours per day, five days per week (many arrive at 7:30 a.m. and leave at 2:30 p.m.). Expatriates who work in the private sector, by contrast, often work six days per week and also work a second shift that starts in the late afternoon. In 2006, Sheikha Lubna, UAE minister of economy, estimated that the average number of working days in the government sector was 180, while it was 275 in the private sector. Other factors, in addition to short workdays, make public-sector employment attractive to citizens. Dismissal is a remote possibility. Qatari nationals who lose their jobs in the state receive their salaries until they find a new one. Throughout the Gulf, citizens can typically retire from the public sector after twenty years of service, with generous pensions subsidized by rent revenues.

Pay packages for citizens in the public sector are set relative to state oil income rather than overall productivity in the economy. According to a World Bank report discussed in Al-Qabas, the average pay for a Kuwaiti government employee was 827 dinars per month in 2007–2008, which amounts to something on the order of $36,000 annually. This income is tax free, and the government subsidizes costs that in richer nonrentiers would be paid by citizens from their own pockets. A newly minted college graduate in the UAE was paid around $26,000 annually in 2005, whereas a foreigner with a university degree earned $8,000 less.

Not surprisingly, most citizens gravitate toward public-sector employment. In a 2001 survey, 80% of UAE college students reported that they hoped to find work in the public sector. A class of Kuwaiti students taught by the author at the American University in Kuwait in 2007 intended to seek government jobs on graduation. And, in point of fact, about 90% of all economically active citizens of the richest rentiers work in the public sector, including SOEs. Exact figures can be hard to come by because of the often sorry state of labor-force statistics in the Gulf rentiers, where basic demographic data are often treated as a state secret. This is especially true when it comes to figures for employment in the military and police (where many male citizens work) or, in some cases, simply for the number of foreigners present in the country. Nonetheless, the Qatar government reports that in 2010, 92% of Qataris worked in the public sector or in SOEs. In the UAE in 2008, 88% of citizens worked in the public sector. In Kuwait, the number of citizens in the private sector was higher, around 20%, in large part because the state pays the salaries of many citizens working in the private sector. In 2013, the cost of these subsidies was expected to amount to US$1.6 billion; the total wage bill in 2011–2012 (including foreigners working for the government) was US$18.4 billion. The ostensible success of Kuwait in moving citizens into the private sector does not mean that all these citizens depend on the private sector for their paychecks. Many, perhaps most, receive much of their pay directly from Kuwaiti oil revenue.

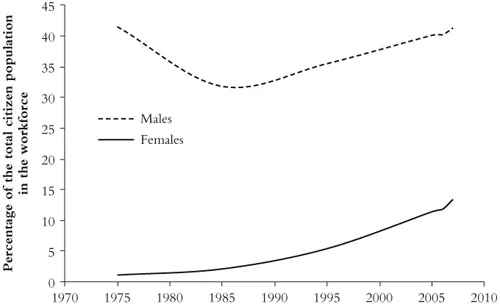

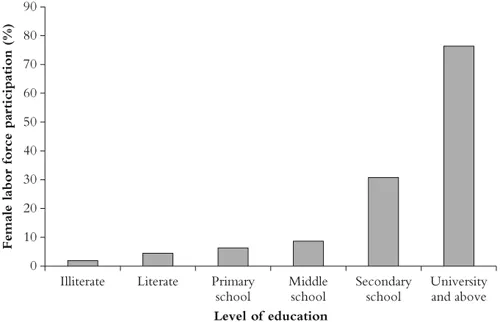

In recent years, citizens have responded to the availability of public-sector jobs by increasing their participation rates in the labor force. That said, this is from a relatively low starting point; early retirement ages, the legacy of the virtually complete absence of women in the salaried workforce in the early days of oil, and stipends for university attendance keep many out of the workforce (see figure 1.1 for changes in labor force participation over time). In the UAE, for example, 28% of citizen women ages fifteen and older participated in the workforce in 2008, whereas 63% of citizen men participated. By way of comparison, the averages for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries are 53 and 70% for women and men, respectively, and the averages for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are 26 and 74%. Historically, it appears that oil led to an initial decline in workforce participation as citizens abandoned the private sector and then to an increase as state policies moved citizens into the public sector, replacing the expatriates who initially had staffed the state bureaucracy. In the UAE, citizen women with university degrees are thirty-five times more likely to hold a job than illiterate citizen women (see figure 1.2). The growth in female labor-force participation is a direct consequence of female education, and especially female university education, which is, in turn, paid for by oil wealth.

Despite the generous employment policies of the richest rentiers, not every citizen receives a job. It appears that those with little education, especially women, are most likely to be denied a public-sector position. Because these citizens are also very uncompetitive in the private-sector job market, failure to secure a public-sector job typically results in unemployment; their “reservation wage” is above the market wage. In 2008, most unemployed citizens in the UAE had never held a job. From one perspective, this unemployment is the result of unrealistic expectations on the part of citizens; they could find jobs if they were willing to lower their reservation wage. A perspective more sympathetic to these citizens (mostly women) would observe that (1) they are not directly receiving their share of the oil wealth through public-sector employment and (2) the wages in the private sector are very low precisely because government policies encourage the importing of labor from very low-cost countries, pushing down the free-market cost of labor to very low levels, especially for less-skilled lab...