1

QUANTITY VS. QUALITY

Soviet Film Policy and the Intolerance of Imperfection

In 1952, Harry Schwartz, The New York Times editorial writer and an expert on the Soviet Union, reported on the “sagging Soviet screen scene”: “Here is surely a phenomenon to cause a mass lifting of the eyebrows. Even Stalin’s most skilled dialectician can hardly be making a Communist propagandist out of Tarzan as played by Johnny Weissmuller and produced in Hollywood. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ original version of nature boy has always been strong on thrills and action, and way low on social significance of the kind the Kremlin prizes so highly. Yet facts are facts. Moscow has resurrected the old Tarzan films, showing them in its theaters, and finding the customers love them. All this after years of raging about Hollywood’s ‘bourgeois decadence.’” The reason for Moscow’s radical turnabout in screen policy, Schwartz suggested, was desperation. The Stalin government had too few Soviet movies to screen.1

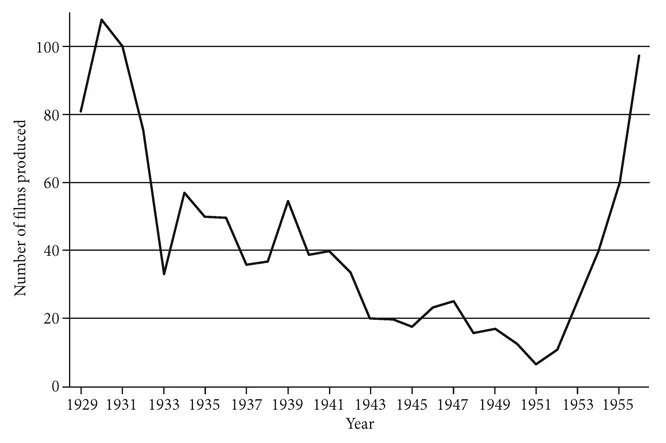

Indeed, perhaps the most striking feature of the Soviet film industry under Stalin was its decline in film output (figure 1.1). The purpose of this book is to explain this decline. To start, it might be useful to establish the tenets of Soviet cinema policy. Was the low output that caused the release of old American films in the late Stalin period part of the party-state’s deliberate policy or an outcome of an unintended policy failure? We now have access not only to Stalin’s public pronouncements but also to the Communist Party Central Committee’s internal deliberations. If we investigate the party-state’s decisions on cinema, as well as the industry’s attempts to implement them, we shall discover that neither low output nor Tarzan were ever part of the plan.

FIGURE 1.1 Soviet film production, 1929–1956

The goal was a “cinema for the millions,” an objective that had both a quantitative and a qualitative dimension. Ideally, the Stalin government, just like Soviet governments before and after Stalin, wanted a mass quantity of successful propaganda films. Both quantity and quality were required to convince naysayers at home and abroad of the superiority of the Soviet regime. Accordingly, Stalin’s Central Committee pursued two policies. The maximum program, as I shall call it, dictated that the film industry make hundreds of mass films and compete with Hollywood. The minimum program prescribed the release of at least a few political and artistic “masterpieces” each year. The implementation of this bifurcated agenda proceeded in spurts that depended on current output. When the number of films made was on the rise, the party-state demanded higher quality and greater selectivity. When quality improved, the industry was instructed to produce more films.

The Soviet mode of film production, however, constrained the implementation of both programs. At the start of the Stalin period, Soviet filmmaking operated under a largely “artisanal” (kustarnyi), or nonindustrial, director-centered mode established in the 1920s. Between 1930 and 1937, the new head of the Soviet cinema administration, Boris Shumiatskii, an ambitious man and a great proponent of genre cinema, tried and failed to reform this mode.2 In 1935 he proposed a project to modernize the industry based on the Hollywood model and to build a cinema city, a “Soviet Hollywood,” in the south of Russia. This proposal, which Stalin initially supported, was part of a policy swing toward the maximum program and had the potential of boosting both quantity and quality. In 1936, however, the policy pendulum swung back to masterpieces and Stalin abandoned the project. The failure of the Soviet Hollywood initiative, with its promise of mass production and comprehensive controls, determined the course of Soviet cinema once and for all. The existing mode of production could not support expansion, precluding the success of the maximum program.

The implementation of the minimum program also backfired, and the Stalin period ended with “the film famine,” a desperate dearth of new releases. This was because every swing toward selectivity was accompanied by sharp criticisms of “average” and “poor” films, which comprised most of the output, as well as by emphatic film bans. Quality was always the priority under Stalin, but his intolerance of imperfection grew over time. Each attack on the industry undermined its productivity, eventually collapsing filmmaking to only a handful of features. In 1948, having realized that the industry was incapable of producing “good” films on a large scale, Stalin had to accept the reality of the vastly reduced minimum program.

From Quantity to Quality, 1930–1933

One of the first major pronouncements by a Bolshevik leader on the role of mass cinema was Leon Trotsky’s article “Vodka, Church, and the Cinema” published in Pravda in July 1923. Not unlike Lenin, who in 1922 reportedly declared cinema a crucial educational medium, “the most important of the arts,” Trotsky argued that cinema was the most critical tool of the party-state for providing the working class with enlightening entertainment during nonwork hours. Trotsky, however, went further than Lenin to suggest that cinema could compete with drinking establishments as both leisure and a revenue source for the state. This fiscal proposition was particularly ambitious given that in 1927–1928 state receipts from vodka sales were projected to reach more than 600,000,000 rubles, whereas receipts from movie theaters in 1926–1927 amounted to less than 20,000,000 rubles.3 Trotsky further proposed that cinema could replace the church. Unlike religion, he said, cinema could tell a different story every hour.4 To displace religion and alcohol, cinema would have to provide not only enlightenment and entertainment but also many new stories in a large number of venues. It had to become a mass phenomenon.

In the 1920s, Soviet cinema showed the potential of meeting this goal. Under the quasi-free-market conditions of the New Economic Policy (1921–1928), studios were mostly self-financed entities selling their products to large regional distributors on a contractual basis. The distributors, in turn, rented films to a dispersed network of exhibitors. Soviet films competed for audiences not only among themselves but also with foreign pictures, and some of them were quite successful at this. The single greatest change that happened under the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), which replaced the New Economic Policy when Stalin solidified his power, was that imports of foreign films were curbed in 1930.5 The measure targeted economic frugality—foreign currency was in limited supply, and far more important commodities could be purchased with it than motion pictures—but it also pursued ideological goals: it helped the Stalin regime to monopolize cultural and political communication.6

Despite this change, the party-state’s conception of cinema as a potential revenue maker persisted to the end of the Stalin period and beyond. In combination with the Bolsheviks’ ambitious ideological agenda, which included transforming everything from the economy to the human psyche, the conception of cinema as a revenue source produced the program maximum for Soviet cinema: “One hundred percent ideology, one hundred percent entertainment, one hundred percent commerce.”7 In a policy speech in 1927, Stalin echoed Trotsky’s idea of replacing vodka sales with “such revenue sources as radio and cinema.”8 In November 1934, when cinema revenues stood at about 200,000,000 rubles, Stalin told Shumiatskii that this was not enough. He added, “You need to seriously prepare yourself to replacing vodka receipts with cinema revenues.”9 Earlier that year Shumiatskii submitted to the Central Committee a proposal that promised to start achieving this goal by the Third Five-Year Plan (1938–1942), when cinema receipts would reach 1 billion rubles.10

It was under the assumption that cinema was a powerful cultural force that in 1930 the Central Committee made all but one of the Soviet Union’s fourteen feature-film studios answerable to one administration, the All-Union Combine for the Cinema and Photo Industry (Soiuzkino), and appointed Shumiatskii at its helm. Soiuzkino’s predecessor, Sovkino (1924–1930), controlled production and distribution in the Russian Republic (RSFSR) alone. Although the names of these studios changed over time, Soiuzkino incorporated the RSFSR studios Mosfilm (Moscow), Lenfilm (Leningrad), and Vostokfilm (which in 1930–1936 also operated the Yalta Studio), as well as studios in the national republics: the Odessa Studio and the Kiev Studio (Ukraine), Belgosfilm (located in Leningrad but producing in the name of Belarus), Gruziiafilm (Tbilisi), Azerfilm (Baku), Armenfilm (Erevan), Turkmenfilm (Ashgabat), Tadjikfilm (Dushanbe/Stalinabad), and Uzbekfilm (Tashkent). The only studio outside of Soiuzkino’s jurisdiction was Mezhrabpomfilm (Moscow). Funded by the Workers International Relief (Mezhrabpom in the Russian abbreviation), a German-Soviet communist organization affiliated with Comintern and headquartered in Berlin, the studio was formed in 1922 as Mezhrabpom-Rus' and renamed Mezhrabpomfilm in 1928. By the 1930s, it was a flagship studio known for its high ticket sales and international filmmaking practices. It employed the A-list directors Vsevolod Pudovkin, Lev Kuleshov, and Yakov Protazanov, as well as immigrant directors, such as Erwin Piscator, who fled the Nazi regime. It was one of the bastions of Soviet internationalism. Mezhrabpomfilm and Vostokfilm were closed in 1936. Soiuzdetfilm, formed out of Mezhrabpomfilm in 1936, inherited the Yalta Studio from Vostokfilm.11 In the 1930s, Mosfilm, Lenfilm, Kiev/Odessa, and Mezhrabpomfilm/Soiuzdetfilm produced the vast majority of all Soviet films.

As head of Soiuzkino, Shumiatskii’s task, along with centralized coordination of production, was to expand output, grow the theater network, and develop domestic manufacturing of film equipment. Soiuzkino and its studios were not vertically integrated, however. In the republics, distribution and exhibition were run by disintegrated administrative units within the national republic governments. Soiuzkino nominally incorporated the republic cinema administrations, but had operational control over distribution and exhibition only in RSFSR. Moreover, the republics, and Ukraine in particular, never accepted Soiuzkino’s monopoly over production. Under their pressure, by the end of 1931 production was again decentralized such that the studios located in the republics were transferred to the republic cinema authorities. This, however, did not establish vertical integration in the republics either, as studios were run separately from distribution and from exhibition. In 1933, Soiuzkino was further decentralized as the Main Administration for Cinema and Photo Industry (GUKF). GUKF no longer incorporated the republic cinema administrations and had veto power only over the production programs of the national studios, such as Mosfilm and Lenfilm. It also lost its control over distribution and exhibition in RSFSR. In parallel with the other republics, these branches were now run by the RSFSR government.12

During Shumiatskii’s tenure the Soviet Union started to manufacture its own film stock, cameras, and projectors, even if of vastly inferior quality compared with imports. A major “cinefication” effort—the expansion of the theater network—also continued, and the number of establishments equipped, nominally at least, to screen silent films grew from seven thousand in 1928 to twenty-eight thousand in 1940.13 Film productio...