![]()

1

Conducting Fieldwork in the Aftermath of War and Genocide

Different interests tell untruths in different ways, and it is a standard part of the anthropological method to reconstruct a more “objective” picture through careful cross-referencing of “versions” and “interests.”

—PAUL RICHARDS, No Peace, No War

The community of “Ngali” lies in the southern portion of Rwanda. Its landscape is low rising hills, dotted with thin clumps of trees and fields of coffee, bananas, corn, and other crops. Key vantage points offer panoramic views of the network of back roads and modest homes that fill out the picture. Admiring this landscape in 2004, I found it hard to fathom that only ten years earlier, these same hills were the site of genocide, carried out by local bands of killers who sought to kill every Tutsi in the community and any Hutu trying to help Tutsi. At the same time, it was difficult to imagine how anyone could have escaped the carnage, so unforgiving was the terrain as to render all movement visible.

To the north of Ngali, toward the Virunga mountain range that marks the boundary between Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies the community of “Kimanzi.” Lava from the mountains makes the soil in this region extremely rich and fertile. As is typical for mountainous regions, the climate is cold. Even in the dry season, morning temperatures often call for multiple layers of clothing, at least until the sun comes out and even then, the chilly mountain air cuts through each layer. People from this region are used to the cold and prefer it to the heat of Kigali—those who have actually been to Kigali, that is, for as some residents will tell you, they have never ventured that far south in their lives.

The terrain of Kimanzi is strikingly different from that of Ngali. Where Ngali is compact, Kimanzi is spacious. Houses, roads, and fields spread out across a much larger expanse. Indeed, in Kimanzi, it is even possible to achieve that rarest commodity in this, one of the most densely populated countries in the world—privacy. Many houses, for example, are not visible from the nearest road or the closest neighbor’s house.

Figure 1.1 “Ngali” secteur, Rwanda, 2004. Photo by Lee Ann Fujii.

The nearest urban centers to Ngali and Kimanzi are the main provincial towns of Gitarama and Ruhengeri. Each town features an array of small businesses, government offices, banks, post offices, and a central prison, the only “gift,” a Rwandan friend joked, the Belgians left behind when they departed the country.

The Belgians built the prison system in the 1930s and the buildings appear to have changed little since that time. One or two guards, sporting rifles that look like they came from the same era, man the main gate where vehicles and pedestrians enter. A simple brick wall extends from the main portal, but does not always extend all the way around the prison grounds. At the main prison in Ruhengeri, for example, the brick wall ends where the prison’s fields begin, providing unimpeded access to the land where prisoners grow crops for food.

Figure 1.2. “Kimanzi” secteur, Rwanda, 2004. Photo by Lee Ann Fujii.

Once inside the gate, one enters the main courtyard, where a variety of activities are usually in progress: a game of volleyball, the odd English lesson, prisoners going to and from their jobs in various prison workshops, while a few others unload supplies from the back of a truck. The most obvious difference between the world behind the gate and the one in front is that those engaged in these various tasks are all dressed in the blush pink uniform of a prisoner. The style and quality of uniforms vary. Most men wear shorts with a short-sleeved, buttoned-down shirt, oftentimes visibly worn. A select few, however, sport uniforms that appear to have been professionally tailored and cleaned, all the way down to their cuffed hems and smartly creased pant legs. It is men in the latter category who greet me in impeccable French.

Inside the courtyard sits an interior building, cut off from the outside world by a windowless steel door. This is the building that houses the inmate population. Since I obtained permission to conduct interviews in the prison courtyard only, I never saw inside this interior space.1

Among the imprisoned population are former residents of Kimanzi and Ngali, accused of having been génocidaires. Some have voluntarily confessed to participating in the genocide in the hope of garnering a reduced sentence, while others maintain their innocence. Both confessed and nonconfessed prisoners are subject to the same dire living conditions, which include a constant shortage of food, sanitation, and medical care. As more than one prisoner told me, were it not for the assistance of the Red Cross, many prisoners would not even have access to a bar of soap.

In 2004, I spent nine months in Rwanda, the majority of that time in one or the other research community and central prison, asking people what they saw and did during the period of the civil war and genocide (1990–94). I also asked people about their lives before the genocide to understand the broader social context in which the events of 1990–94 took place. Because these interviews provided the bulk of the data for this book, the methods I used to collect the data merit extended discussion.

Selecting Sites and Respondents

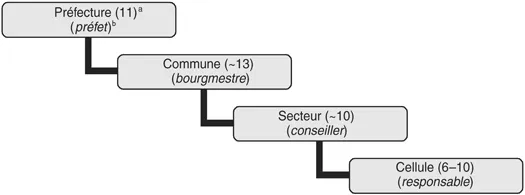

In 1990, Rwanda’s official population of 7,157,551 was spread out across 10 préfectures, 145 communes, and 1,490 secteurs (République rwandaise 1994, 8, 12). The government added an eleventh préfecture in 1992, turning the capital city of Kigali into its own administrative unit (Des Forges 1999, 41). The vast majority of the country’s 7 million inhabitants lived in the rural hills outside Kigali and made their living as subsistence farmers, cultivating an assortment of staple and cash crops. Some people made extra money working as day laborers in brick factories (André and Platteau 1998, 14; Jefremovas 2002) or as local merchants selling traditionally brewed beer. Fewer still had salaried jobs as teachers or clerks or as lowlevel bureaucrats in the large party-state apparatus (de Lame 1996).

To understand how ordinary Rwandans made sense of what happened in their communities during the period 1990–94, I chose two rural communities in two different regions of the country: Ngali in the central province of Gitarama and Kimanzi in the northern province of Ruhengeri. I selected these two communities to capture important historical differences that have long distinguished north from south in Rwanda. The northern préfectures have always had the smallest percentage of Tutsi in the country. The provinces in the center and south of the country, by contrast, have generally had higher proportions of Tutsi than in the north. Each region has also been the home base for a president. Grégoire Kayibanda, Rwanda’s first president, heralded from Gitarama, while Juvénal Habyarimana, Kayibanda’s successor (through a coup), came from Gisenyi in the northwest.

In addition to historical, political differences, the two regions also had very different experiences of the war and genocide. People in Ruhengeri (in the north) experienced the civil war between the RPF and Rwandan government forces (FAR) firsthand, and from the very beginning of the conflict. The first mass killings of Tutsi in Ruhengeri took place in January 1991 after an RPF attack on the main town. People in Gitarama, by contrast, had no direct experience of the war or mass killings of Tutsi until the plane crash that killed President Habyarimana on 6 April 1994.

Because of these differences, I expected the two sites to provide diverse, perhaps even competing, accounts and explanations of the period 1990–94. My field research, in many ways, confirmed this expectation.

The selection of the precise sites where I conducted my interviews was based on two factors, one methodological, the other practical. Because I was interested in violence committed by neighbors against other neighbors, I sought communities that were mostly rural, since urban centers tend to be dominated by higher-level authorities, such as préfets, who, in turn, have access to different types of armed resources (such as communal police). To help to ensure that my research sites were not dominated by provincial-level authorities or elites, I chose communes within each province that were located outside the main provincial town. While this strategy did not guarantee that the two sites were more rural than urban in their orientation (since the remotest hills in Rwanda still maintain connections to urban centers, including the capital [de Lame 1996]), it helped to focus attention on local, and not just town, elites.

Within the two selected communes, I chose two secteurs (the administrative unit just below a commune as shown in figure 1.3) that were within a thirty-minute drive of the main paved road. I call the two secteurs I chose “Kimanzi” and “Ngali.” I use pseudonyms for most place names below préfecture and for all the people who talked to me to protect their identities.

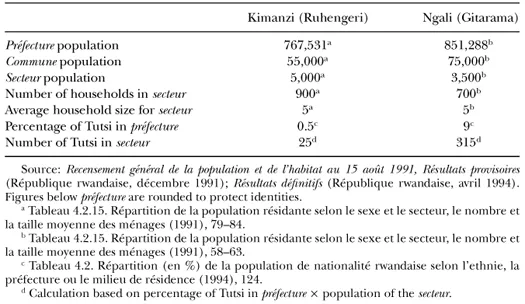

The most significant demographic difference between Kimanzi and Ngali is the relative and absolute number of Tutsi in each locale. As table 1.1 shows, the number of Tutsi in Kimanzi was extremely small—around twenty-five or so people according to the 1991 government census. This figure also matched residents’ estimates. The small number of Tutsi in Kimanzi necessitated going beyond the immediate research site to talk with Tutsi survivors from neighboring secteurs in order to obtain a more detailed picture of what occurred in the area. Tutsi from neighboring secteurs were fair proxies for Tutsi from Kimanzi in terms of their experiences during the period of the civil war and genocide (1990–94), since most Tutsi fled in similar directions and at similar times. In Ngali, the number of Tutsi was much larger, but even here, I included three people who fled to Ngali from other secteurs. Having fled to Ngali, these people could also provide an important vantage point on how violence unfolded in Ngali and neighboring areas.

Figure 1.3 Administrative hierarchy in Rwanda in 1990–94

aNumber of units contained in the unit above. Thus the number “11” next to “Préfecture” means that in 1994, the country was comprised of 11 préfectures, each of which included approximately 13 communes.

bHead of the administrative unit.

Ngali and Kimanzi secteurs were each made up of six to seven cellules. A cellule is comprised of roughly one hundred households. Because of the small number of Tutsi in Kimanzi, there were cellules that had no Tutsi whatsoever. In Ngali, by contrast, there were Tutsi in all six cellules.

Across the two sites, I conducted 231 semistructured, individual interviews with 82 different people (37 people in Kimanzi and 45 in Ngali).2 In addition to one-on-one interviews, I conducted two group interviews, one in each research site.3 (See table 1.2 for the breakdown of interviews in each site.) All of the people I interviewed had lived in one or the other community (or neighboring community in the case of “Kimanzi” respondents) at the start of the civil war in 1990, except for three people who fled to Ngali at the start of the genocide.

Table 1.1 Official 1991 population figures for the two research sites

Table 1.2 Breakdown of interviews by research site

Of the eighty-two people I interviewed, twenty-eight were in prison at the time of my field research, all accused of having participated in the genocide. Sixteen of the twenty-eight prisoners I interviewed had taken part in a government program that offered the possibility of a reduced sentence to prisoners who voluntarily confessed their participation in the genocide. At the time of my fieldwork, none of the confessed prisoners I spoke with had had his dossier processed, so all had yet to benefit from the program. Of the twelve prisoners who did not confess, two had already been sentenced (one to life in prison and the other to death); the remaining ten maintained their innocence and thus elected not to confess.

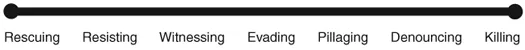

Figure 1.4 Spectrum of responses to genocide

The research design drew its inspiration from Kristen Monroe’s (1991; 1996) work on altruism. To investigate altruistic behavior, Monroe constructed a continuum of rational behavior, anchored by self-interested actors at one end and selfless (altruistic) actors at the other. To study mass-level participation in violence, I constructed a spectrum of responses to genocide. At one end of the spectrum, I placed the least or anti-violent response, which I identified as “rescuing,” and at the other, the most violent, which I identified as “killing.” In between those two poles I hypothesized a wide range of responses, including refusing to participate in the violence (resisting); witnessing without taking part in the violence (witnessing); avoiding participation in the violence (evading); turning people in to authorities (denouncing); and pillaging property (pillaging). I arrived at some of these categories prior to going to the field; others emerged during the course of the fieldwork, as I learned from people’s testimonies the kinds of actions people actually took during the genocide. What the spectrum provided was a way to think both deductively and inductively about the actions people took or could have taken during the genocide. Figure 1.4 shows the spectrum of responses to genocide that guided the research.

I used a purposive selection strategy to find people whose experiences represented as much of the spectrum as possible. The people I interviewed included those who killed, rescued, and resisted as well as those who pillaged, profited, and protested; people who fled the violence as well as those who stayed put; prisoners who confessed their participation in the genocide and those who maintained their innocence; people imprisoned during the war and genocide (1990–94) and those imprisoned afterward; people who claimed to know little about what happened and those who claimed to have seen everything. Missing in this group were some local leaders of the genocide, many of whom were already dead by the time of my fieldwork or living in exile. In these cases, I queried others about them. The goal of these and other strategies (discussed below) was to capture a wide range of vantage points to ensure that the data did not privilege any single perspective, such as, for example, the perspective of survivors, who had but one view of the violence. A random selection strategy could not guarantee this type of broad perspective.

Among the people with whom I spoke, I tried to achieve a balance of men and women and a diversity of ages. I was only partially successful at achieving gender balance. In both research sites, male respondents outnumbered female respondents by four to one. The reason for the gender imbalance is that many women did not volunteer to be interviewed, claiming they were too busy to talk or had nothing to say. Men, by contrast, were generally, though not always, more available and willing to talk with me.

Respondents’ ages ranged from thirty to eighty at the time of interviews, making the youngest person I interviewed twenty-one and the oldest in her seventies at the time of the genocide. Ages are imprecise because some respondents gave different birthdates at different interviews.

One age cohort I sought out specifically was those born before 1950. I wanted to talk to people who were old enough to remember the seminal events of 1959–61, when political violence first took center stage in Rwanda. Older people, I reasoned (and my interviews confirmed), had lived history and thus had more stories to tell. I was also interested to see if those who lived through past periods of violence drew links from past events to the more recent genocide. Some people made a link, though others did not. Age seemed to be a defining factor as no one born after 1950 ever drew a link. As one younger respondent told me, for example, comparisons of the RPF invasion to cross-border raids by Tutsi exiles in the 1960s meant nothing to him, since the war with the RPF was the first he had ever known. Thus, in order to probe the extent to which people linked past episodes of violence to genocide, I had to find people who were old enough to have lived through these events, or alternatively, find people who were familiar with past episodes through stories passed down from older people. I found few of the latter, which suggests that older people do not generally pass down stories of past violence, or, if they do, that the younger generation did not think to share them with me or did not think of them when talking to me about the genocide.

One criteria that I did not use for selecting people was ethnicity. One reason was that government policy at the time forbade any talk of Rwandan ethnicity publicly and privately. This meant it was not possible to ask a person directly if she was Hutu or Tutsi, or to ask for people by ethnicity when asking local authorities to suggest people who might be willing to talk with me. And because Rwandans all speak the same language (Kinyarwanda), live in the same face-to-face communities, dress similarly, share the same names, it is not possible to deduce a person’s ethnicity from looking or talking to her or knowing her name. In addition, religious identity does not coincide with ethnic identity in Rwanda. Put simply, choosing people according to their ethnicity was not possible had I wanted to do so.

The other reason for not using ethnicity as a selection criteria was methodological. Because I was interested in understanding participation in the genocide, my priority was to gain the widest representation of responses possible—regardless of the actors’ ethnicity. Not knowing people’s ethnicity also had its advantages. It forced me to ask questions I would not otherwise have asked. The fact that no one told us up front what their ethnicity was did not mean that I a...