1

Mapping Social Welfare Regimes beyond the OECD

Ian Gough

This chapter maps welfare regimes across countries that are not members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Building on earlier work with Geof Wood and Miriam Abu Sharkh, I distinguish three types of welfare regime: “welfare states,” “informal security regimes,” and “insecurity regimes” (Abu Sharkh and Gough 2010; Gough et al. 2004). The chapter illustrates the wide and at times puzzling variation to be found among the middle-income group of informal security regimes that are the focus of this volume. At the same time, this exercise is hampered by a severe lack of comparable international quantitative data on many aspects of non-state welfare provision. It thus illustrates the signal importance of this book in exploring this territory.

This chapter is organized in four sections. First, the welfare regime concept is theorized and the three metaregimes identified. Next, these are crudely operationalized and a series of regime clusters are mapped across sixty-five countries. The third section identifies correlates of these clusters to begin to explain some of the differences between them. The final section then draws on the introductory chapters and case studies in this volume to illustrate the diversity of contexts in which different non-state welfare providers operate across the developing world, before drawing some conclusions.

The Concept of Informal Security Regimes

I start from our earlier work on welfare regimes in developing countries (Gough et al. 2004; Wood and Gough 2006). This in turn built on Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s influential book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Esping-Andersen 1990), which proposed the idea of welfare state regimes. His approach remains a fruitful paradigm for thinking about social policy across the developing as well as the developed world for several reasons. First, it situates modern “welfare states” within a wider welfare mix: governments interact with markets and families to produce and distribute welfare. Thus it pays attention to some forms of non-state welfare—but by no means all—and their interaction with state systems and complements the typology of NSPs presented in chapter 2. Second, it pays attention to welfare outcomes, the final impact on human security, need satisfaction, and well-being. Third, it is a sociological or political economy approach that embeds welfare institutions in the “deep structures” of social reproduction: it forces researchers to analyze social policy not merely in technical but in power terms. Welfare regimes spring from particular “political settlements” (such as that between labor, capital, and the state after World War II) that define the shape of welfare state regimes and then provide positive feedback, shaping political coalitions that tend to reproduce or intensify the original institutional matrix and welfare outcomes. As a result, this framework also posits a strong thesis of path dependence.

Esping-Andersen (1990) developed the welfare regime framework as middle-range theory. Studying developed, capitalist, democratic nations, he argued that there are “qualitatively different arrangements between state, market, and the family” and rejected simplistic rankings on one dimension. In this way he distinguished three worlds of welfare capitalism: the social democratic world in the Nordic countries, the liberal world in the Anglophone countries, and the conservative or corporatist world in many western European countries. Others posit the existence of distinct southern and central European worlds, but the basic model as applied to advanced Western economies has received considerable empirical support over the last two decades (Castles et al. 2010).

Though there have been attempts to apply the regime framework to other parts of the world, most of these, apart from numerous single country studies, adopt the original conceptual framework developed to understand the OECD world (e.g., Lee and Ku 2007). Rudra’s ambitious study (2007) uses cluster analysis to distinguish between “productive” and “protective” patterns of welfare effort in developing countries. Protective policies are designed to shield or decommodify labor against risks, whereas productive policies aim to invest in labor to make it more employable in open competitive economies. This is an important distinction in developing countries, but it remains focused on the public sector as do all her variables. One study stands out: Haggard and Kaufman’s (2008) comparative study of development, democracy, and welfare states in Latin America, East Asia, and eastern Europe. A wealth of data is gathered on twenty-one middle income countries in the three regions and analyzed using both cross-section and time-series methods. At the same time, Haggard and Kaufman recognize throughout the profound importance of long-term historical processes and utilize a wealth of qualitative knowledge about the individual countries. This historical perspective and the continuing significance of regional factors sets up their regional comparison, but these regional “models” are not so much an outcome as a presupposition of the exercise. They also adopt several aspects of welfare state regime studies in the developed world: the focus remains on government social programs in health, education, and social security, and their conceptual framework adopts and extends factors common in studies of welfare states: distributional coalitions, the growth and organization of the economy, political institutions ranging from democracy to authoritarian, and welfare legacies. Their work is of outstanding importance in understanding the welfare state in middle income countries, but it does not significantly broaden our understanding of welfare regimes (a phrase they hardly ever use).

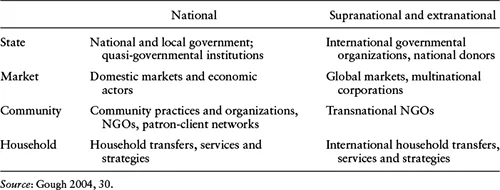

Gough et al. (2004) contend that to apply the welfare regime paradigm to the nations and peoples in developing countries requires a radical reconceptualization in order to recognize the very different realities across the world. In essence, there must be a broadening of focus from welfare state regimes to welfare regimes. In particular, the welfare mix must be extended beyond “the welfare state,” financial and other markets, and family/household systems. The important role of community-based relationships must be recognized, ranging from local community practices to NGOs and clientelist networks. In addition, the role of international actors cannot be ignored as it often has been in the welfare state literature: this embraces aid, loans, and their conditions from international governmental organizations, the actions of certain transnational markets and companies, the interventions of international NGOs, and the cross-border spread of households via migration and remittances. The result is an extended welfare mix or institutional responsibility matrix as illustrated in table 1.1.

On this basis, we posit the existence of two other meta-welfare regimes in the modern world: an informal security regime and an insecurity regime (Gough et al. 2004).

Informal security regimes describe institutional arrangements where people rely heavily on non-state institutions and relationships—including private markets, community, and family—to meet their security needs (though to greatly varying degrees). These institutions and relationships are variegated and have evolved over long periods of time. However, in the contemporary period they increasingly interact with state institutions and power inequalities. Wood argues that they are often hierarchical and asymmetrical. This often results in problematic inclusion or “adverse incorporation,” whereby poorer people acquire some short-term assistance at the expense of longer-term vulnerability and dependence (Wood 2004). The underlying patron-client relations are then reinforced and can prove extremely resistant to civil society pressures and social policy reforms along welfare state lines. Nevertheless, these relations comprise a series of informal “rights” and afford some measure of security. The bulk of the NSPs examined in this book operate within this type of system, in which some public welfare institutions operate, albeit imperfectly, alongside an array of non-state actors.

TABLE 1.1.

Components of the institutional responsibility matrix or welfare mix

Insecurity regimes describe institutional arrangements that block the emergence even of stable informal security mechanisms, and thus generate gross levels of insecurity and poor welfare outcomes. These regimes often arise in areas of the world where powerful external actors interact with and reproduce weak state forms, conflict, and political instability (Bevan 2004). The result is a circle of insecurity, vulnerability, and suffering for all but a small elite and their enforcers and clients.

The focus of this book is the “middle” category of informal security regimes.

Mapping Informal Security Regimes

Esping-Andersen (1990, 26) writes: “The linear scoring approach (more or less power, democracy or spending) contradicts the sociological notion that power, democracy, or welfare are relationally structured phenomena…. Welfare-state variations are not linearly distributed, but clustered by regime types.” Regression analysis using cross-sectional data is not well suited to identifying recurrent patterns and “stickiness” in national patterns (Abu Sharkh 2007). For this reason Miriam Abu Sharkh and I (2010) claim that cluster analysis is the most suitable method to test these arguments (see Abu Sharkh and Gough 2010 for full details and arguments).

To map welfare regimes, we need data on at least two of the dimensions originally theorized by Esping-Andersen (1990): the welfare mix and welfare outcomes. The welfare mix describes the entire pattern of resources and programs that can act to enhance welfare or security in a nation state. However, to operationalize this across the non-OECD world is exceptionally difficult, not least because of lack of data. Thus we could find no valid, reliable, and comparative measures of: privately provided pensions and services (except for health purchases); community and NGO-provided welfare; the role of households and wider kin groups, except for overseas remittances; and little on the role and influence of transnational actors, except aid donors. Given this unfortunate fact, we are reduced at this stage to inferring the nature of informal and insecurity regimes from the data that are available.

To capture the extent of state responsibility for critical social resources, we use two pairs of variables covering expenditure/revenues and service delivery. This reflects the concern of Esping-Andersen that public expenditure is a poor indicator of welfare regimes. We must perforce rely on this given data inadequacies in developing countries, but we are able to complement it with information on public service outputs (to be distinguished from welfare outcomes below). The first pair are:

• Public spending on education and health as a share of Gross Domestic Product

• Social security contributions as a share of total government revenues (as a proxy for provision of social insurance benefits).

This provides us with indicators of both of Rudra’s (2007) “productive” and “protective” forms of social spending. The second pair are:

• Immunization against measles: a fairly restricted social policy target

• Secondary school enrollment of females: a higher, more extensive output target.

To represent international aspects of the welfare mix we have measures of two external transfer flows:

• Official aid

• Remittances from overseas migrants.

To measure welfare outcomes we wanted to use the classic human development indicators of life expectancy, literacy, and poverty. However, because of doubts about the reliability of poverty estimates we relied on the first two indices:

• Life expectancy at birth

• The illiteracy rate of young people aged 15–24 years.

Miriam Abu Sharkh and I (2010) use cluster analysis to map the patterns of these variables for sixty-five non-OECD countries in 1990 and 2000. We undertook cluster analysis in two stages: hierarchical cluster analysis and k-means cluster analysis. All variables were standardized before beginning the analysis. Hierarchical cluster analysis identifies relatively homogeneous groups of countries according to the selected variables based on an algorithm that starts with each country in a separate cluster and combines clusters until all form a single cluster. Dendograms are generated that provide a visual aid to assess the cohesiveness of the clusters formed and the appropriate number of clusters to keep. Yet the final choice of the number of clusters remains a judgment call.

Hence we use a second stage k-means cluster analysis to improve this judgment (another contrast with Rudra [2007]). This is designed to identify relatively homogeneous groups of cases based on selected characteristics, using an algorithm that requires one to specify the number of clusters in advance: this number can be generated by theories or by previous observations. In this case, the number was generated by observation of the dendograms generated by the hierarchical clustering. Following numerous trials, we settled on ten clusters, of which two comprise single countries, leaving us with eight (see Abu Sharkh and Gough 2010 for more details). A k-means cluster analysis also calculates the distance between cluster centers, which enables us to order the clusters, as described below.

Our data sets exclude the OECD world: these rich countries are sufficiently distinct that their inclusion can diminish discrimination within the rest of the world. In order to avoid large numbers of smaller states, we also exclude countries with a population of less than three million people. This left potentially 127 countries and a final tally of sixty-five countries with sufficient data. This analysis generates eight country clusters, which can be ordered according to the distances of their final cluster centers from the OECD welfare states (see table 1.1). The cluster with the highest scores for public expenditure, public provision, and welfare outcomes is labeled A. Most remote from this cluster are clu...