1

PICKING SITES

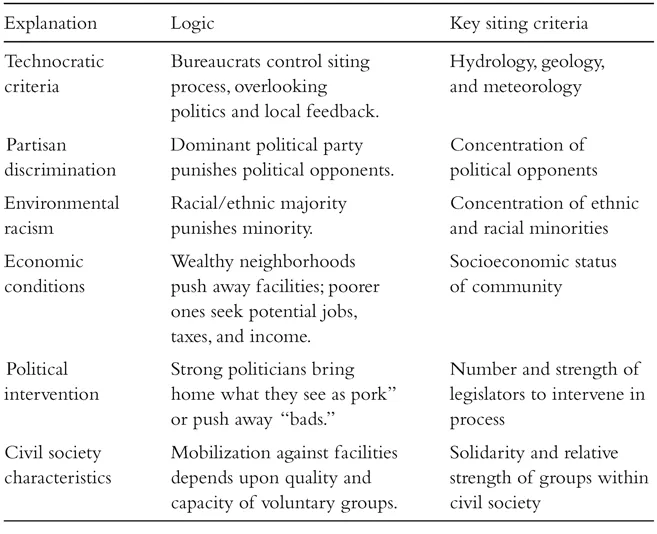

HOW AUTHORITIES SITE PUBLIC BADS is a matter of great controversy among observers. This chapter argues that authorities base their choice among technically appropriate sites on the strength of local civil society. In a handful of cases, powerful legislators intervene in the siting process to place these projects in their own districts. Available data from Japan support these explanations over other accounts, including concentrations of minorities, partisan discrimination, and local economic conditions.

Explanations for Siting

Different observers see dissimilar landscapes when analyzing how authorities choose where to locate public bads. Table 2 lays out six approaches along with their key siting criteria. Whether in Japan, France, or the United States, government officials and developers involved in choosing locations for such projects typically hold that technocratic criteria—earthquake-resistant bedrock, sufficient water supply, distance to existing infrastructure—dictate site choices (author’s interviews, 2002–2003). Areas that meet such specified technical qualifications as the ability to withstand strong seismic activity, or proximity to electrical grid and transportation networks, are ranked accordingly. Public officials regularly defend their siting of projects on the basis of such neutral technical criteria (Morone and Woodhouse 1989, 75; Denki jigyō kōza henshū iinkai 1997, 278–279; Quah and Tan 2002, 19). These neutral criteria do exclude inappropriate sites, but placement within feasible locations is not random. Once necessary technical features for sites have been taken into account, other factors influence the siting decision.

A landscape centered on partisan discrimination might be painted in shades of blue and red (in the United States) or green and red (in Europe) to reflect local political support for opposition or in-office factions. Researchers who adopt this approach argue that in one-party-dominant systems, such as Japan, Mexico, and Sweden, towns supporting the opposition party are punished with a higher concentration of public bads such as nuclear power plants (Ramseyer and Rosenbluth 1993, 129). In Japan, for example, towns and villages that strongly support Socialist or Communist parliament members would be saddled with unwanted facilities as payback for their opposition to the dominant Liberal Democratic Party, and communities that have long supported the LDP would be expected to be free of such facilities. Fiona McGillivray (1997, 586) makes a similar argument about high-discipline, majoritarian systems: “The government will inflict costs on party loyal districts while providing protection to industries concentrated in marginal districts. In low party discipline majoritarian systems, such as the United States, industries in marginal seats are the least likely to receive favorable levels of protection.” Although past studies have argued for this approach, I find no supporting evidence that Japan’s long-ruling LDP punishes opposition-supporting localities.

Table 2. Six explanations for siting outcomes

Proponents of the environmental racism argument see controversial and unwanted facilities located in clusters of ethnic, racial, and religious minorities (Falk 1982; Gould 1986; Austin and Schill 1991; Hurley 1995; Pastor, Sadd, and Hipp 2001). Such landscapes center on disadvantaged groups who bear the brunt of public bads. In the United States, for example, many waste repositories and incinerators are found in communities with large populations of African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics (Bullard 1994). A variety of community advocacy groups have formed to combat what they see as policies harmful to communities of people of color. Given the small numbers of minorities and the technical requirements for large-scale projects, however, this explanation cannot apply to nuclear power plant, dam, and airport siting in Japan.1 One can dismiss arguments that Japanese authorities site such facilities in areas with high concentrations of minorities, since in fact they cannot be located in large metropoles. Further, second-level tests of the environmental racism hypothesis uncover no systematic attempts to locate nuclear power plants, dams, or airports in Hokkaido and Okinawa, areas known for their minority populations.

Another common explanation for the siting of public bads focuses on the economic conditions in local communities. For example, small towns in rural North Carolina are said to view prisons as public goods because they bring jobs and other economic benefits (Hoyman 2001), despite fears of jail breaks, riots, and negative effects on the neighborhood. Others argue that such facilities as industrial waste dumps and incinerators are likely to be found in communities with lower levels of income (Mohai and Bryant 1992). But I find little evidence that economic conditions determine these siting outcomes, for economic conditions in communities selected for these public bads differ little from those in similar rural towns nearby that were not chosen. Around 41 percent of workers in Japanese towns selected to host nuclear power plants, for example, are in white-collar occupations, on average only 1 percent less than in towns that meet the same technical requirements but were not selected as hosts. Studies of waste facilities in Canada similarly dismissed claims that their siting was based on economic disadvantage, whether measured in terms of either income or unemployment (Castle and Munton 1996, 78).

Another map of siting would focus on clusters of powerful politicians to illuminate political intervention. Analysts have shown that both politicians and governmental authorities do manipulate benefits and costs to fall on specific constituencies, within certain constraints. As “agenda setting [is] fundamentally biased in favor of those who possess the most resources” (Berry, Portney, and Thomson 1993, 103), powerful incumbent legislators can intervene to alter bureaucratic processes so as to focus costs and benefits on a locality-by-locality basis (Weingast, Shepsle, and Johnsen 1981, 643). In the late 1970s, for example, government bureaucrats at the Tennessee Valley Authority, working to complete the planned Tellico Dam, found themselves blocked by the discovery of an endangered fish in the local waters. Fearing that the Endangered Species Act would terminate the dam plans, Congressman John Duncan offered an amendment to a “sleepy and near empty House of Representatives” that exempted the project from the act. On a voice vote that took less than a minute, political intervention saved the project and provided jobs, infrastructure, and revenue to affected areas (Wheeler and McDonald 1986, 212). Similarly, North Carolina politicians have intervened to guide prisons to their districts even though earlier site selections have not favored their constituencies (Hoyman and Weinberg 2006). Japanese politicians do occasionally intervene when they have sufficient political power to override bureaucrats and siting authorities, but doing so requires that several powerful legislators work together to override decision-making processes.

A final map of the siting landscape highlights the characteristics of civil society. This approach centers on the relative strength of horizontal associations, the ties between individuals, and the depth of shared norms and behavioral expectations. Previous research linked how closely local citizens work and play together to their ability to impact projects slated for their backyards. Research on siting in North America has demonstrated that private developers avoid areas of high potential to mobilize against their projects (Hamilton 1993). Authorities recognize that tighter-knit, better-connected communities will mobilize more strongly against proposed public bads than those with looser connections. For example, local areas made up of homogeneous constituents—that is, those with strong horizontal bonds between citizens—are more likely to create zoning policies that exclude unwanted group homes (Clingermayer 1994). The more social capital in a community and the better its networks, the easier it is for antifacility groups to mobilize and organize against unwanted projects. I find strong evidence in Japan that the quality and relative capacity of social capital in localities influence site selection authorities exclude those areas with stronger and more numerous social ties and in favor of localities with weaker connections.

Siting Decisions, Civil Society, and Proxies

Decision makers choose from an array of sites that meet geographic and geological criteria and then select the localities that seem most likely to cooperate, or least likely to resist, as host communities. State authorities base their estimates on both the quality and relative capacity of civil society (cf. Tilly 1994; Sheingate 2001). The quality of civil society is the strength and depth of bonds between citizens; neighborhood associations with high levels of participation, for example, can better monitor crime, push for upgrades to local facilities, and maintain community standards than those with declining or nonactive memberships. Previous studies have shown that rapid population growth increases turnover (Hammel 1990, 185), breaks apart community connections, and increases alienation (Freudenburg 1984). Rapid population changes that are due to events such as economic development are often associated with broad, negative social impacts such as increases in crime (Siegel and Alwang 2005, 7), increases in gang population (Spergel 1990, 232), and a breakdown in local networks. Areas where population levels have remained stable are more likely to have intact social networks that allow citizens to overcome collective action problems and to mobilize for such purposes as protesting unwanted facilities.

Authorities envision localities experiencing a large influx of newcomers as good hosts for controversial facilities because protest efforts in these communities are more vulnerable than elsewhere and likely to fracture under pressure (Putnam 1993; Munton 1996, 307). When bureaucrats and developers can site in areas where low potential for resistance is due to nonexistent or low-quality social capital, they do so. The Palo Verde nuclear power plant complex in Arizona, for example, optimizes the siting goals of planners, as census and ZIP code data reveal the abutting population to be zero; the reactors literally sit in the center of a desert. Planners for the new Denver airport found an ideal site: 4,450 hectares of uninhabited land in Adams County, located adjacent to the defunct but heavily polluted Rocky Mountain Arsenal site (Altshuler and Luberoff 2003, 159). In Japan, existing nuclear power plants have been placed in depopulating areas with less than one-third the average nationwide population density (Oikawa 2002). Because past research has demonstrated that rapid population change, either up or down, affects the quality of social ties, I measure community solidarity in Japanese localities through change in population from 1950 until the time of the siting attempt in order to capture broad trends in local ties.

The relative capacity of social capital can be determined by comparing the size of participating organizations’ memberships with that of their opponents and competing groups. For example, Robert Putnam (2000) mourns declining membership and participation rates in community, fraternal, and civic organizations as signs of disengagement from political and public life. Sheingate (2001, 27) emphasizes that organizations with higher relative capacity maintain advantages over competing groups because they can better capture limited resources. As in previous studies of facility siting, the relevant civic groups most likely to be active in siting processes for controversial facilities are cooperatives made up of farmers and fishermen (cf. Lesbirel 1998; Garcia-Gorena 1999). Because the technical requirements for nuclear power plants, dams, and airports regularly place these facilities in rural areas, these primary-sector workers often participate in siting processes and, more important, regularly join together in collectives and associations. In Japan, fishermen’s cooperatives (gyogyō rōdō kumiai) hold veto powers over the siting process (Tsebelis 2002); for the plant to proceed, a majority must agree on a contract with site developers (Lesbirel 1998; Aldrich 2005a).2

Furthermore, the concerns of fishermen and farmers have been heightened by past accidents and by the potential impact on their livelihood. Developers sited all Japan’s nuclear power plants near the ocean, where the process of cooling the reactors draws in ocean water and expels waste water at a temperature 6 degrees Celsius higher than that of ambient water. Fishermen became alarmed over this practice after studies showed that the plants were releasing not only hot water but radioactive elements into the ocean (NGSK 10/2 [1966]; AS, 23 March 1972; CNFC 36 [2002]: 3). Along with fears about direct effects on their jobs and health, fishermen and farmers regularly express concern about “nuclear blight”: that is, the contamination of their produce and harvests, and sales lost because of fears or rumors of radioactivity (see Tabusa 1992, 244).

The Japanese government and utility developers have long recognized the importance of studying the concentration of fishermen in potential public-bad sites. When the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) worked with MITI to site reactors in Fukushima prefecture in the early 1960s, it measured levels of commercial fishing and took into account membership in local fishing cooperatives. Argument for siting in the area of Futaba-machi hinged on the point that it was “not an important area for fishing” (NGSK 8/6 [1964]: 21). Similarly, when Chubu Electric Power Company began to survey the Ashihama district near the Kumano Sea, it predicted that the area would be more amenable to nuclear power plant siting than the nearby village of Oshiraike because it had fewer fishermen’s cooperatives (NGSK 8/8 [1964]: 42). Nuclear plant developers bemoaned the fact that even though they had done their best to pick rural areas where resistance would be low, local fishing cooperatives would likely cause “problems to arise over new projects.” Fishermen sought to move beyond local issues when they organized a national forum of fishing unions to discuss the problem of siting (NGSK 10/11 [1966]: 15).

Political power can increase with both absolute (Acemoglu and Robinson 2001; Fung 2004) and relative (Sheingate 2001) group size. Larger groups can amass more votes and donations, as well as letter writers and protesters, and can better pressure state leaders and decision makers. When facing off against competing civil society organizations, relatively stronger groups can better achieve their goals. Smaller groups, conversely, are less powerful, less able to bring political power to bear on decision makers.3 In reviewing potential host communities, however, I found that the long-term capacity of voluntary associations, not just the size of relevant groups at the initial siting attempt, forms the core concern for state authorities: facilities such as Logan International Airport’s additional runway in Boston and the Higashidōri nuclear plant in Japan can take up to three decades to site (AP News, 18 April 2005; Lesbirel 1998). Siting authorities analyzing potential sites for atomic reactors in Japan, for example, calculate that villages suffering from problems such as depopulation of fishermen, low community solidarity, and pollution are less able to resist siting attempts, which might still be going on in twenty years.

State authorities and developers can forecast the mobilization capacity of Japanese fishing and farming ...