CHAPTER 1

Power, Violence, and Victory

Zohra Drif, Leila Khaled, Gerry Adams, and Yoske Nachmias all wanted the same thing—a state for their people to call their own—and they all played a prominent role in the struggle to achieve it. Yet when I was interviewing Zohra Drif a stone’s throw from the Milk Bar she had bombed in Algiers, discussing Leila Khaled’s hijackings and struggle for Palestinian rights in a refugee camp, walking next to Gerry Adams in one of multiple competing Irish republican marches to Bodenstown, and talking with Yoske Nachmias about facing his own brother in a firefight while aboard the Altalena off the Tel Aviv coast, I was struck by how different the outcomes were for their nations and the organizations of which they were a part.

Zohra Drif helped achieve an independent Algeria in 1962, and her Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) rules the country to this day. In contrast, Leila Khaled and her fellow Palestinians still do not have a state, and her Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) finds itself on the margins of the enduring Palestinian national movement. Gerry Adams and Yoske Nachmias face mixed outcomes. Although Adams finds himself at the head of Sinn Féin, a powerful political party with the potential to become the largest in Ireland, he has been unable to bring Northern Ireland into the Republic. Nachmias celebrated the independence of Israel in 1948, but his Irgun was repressed and disbanded by its Zionist rival, and its affiliated party was excluded from power for three decades.

What explains this variation in outcomes? Why did some national movements achieve states while others did not? And what explains the accompanying variation in behavior, in that all four of these groups differed in their use and support of violent and nonviolent tactics across time and space? These are not simply historical puzzles; they are at the forefront of politics today.

Gaza has experienced a significant crackdown on cross-border violence into Israel and the Egyptian Sinai over the past five years. Members of the PFLP have been detained; members of Jaish al-Islam who took Western journalists hostage were arrested; a leader of Islamic Jihad was killed after his involvement in rocket fire against Israel; the flow of fighters and arms into Sinai has been inhibited; the jihadi group Jund Ansar Allah has been all but destroyed; and negotiations commenced with Israel over a long-term cease-fire.1 The most surprising fact about this entire effort is that each of these actions was taken not by Israel, or Egypt, or even Fatah—but by Hamas.

Why would Hamas, the Palestinian group most associated with political violence against Israel over the past two decades, now restrain violence by the PFLP and negotiate with its enemy? Hamas has not undergone a change in leadership, its ideology and objectives have not been amended, and Israeli counterinsurgency tactics in Gaza have not been transformed. Existing theories would predict precisely the opposite behavior by these armed groups, arguing that groups become less violent with age but more violent with religious ideology and a higher number of total groups in a movement. It should, therefore, be the PFLP restraining Hamas and negotiating with Israel, but the reality is an Islamist Hamas with maximal territorial demands operating amid an increasing number of factions actually constraining the violent actions of the PFLP, a far older group with a secular ideology.

Just before Hamas repressed other Palestinian groups in Gaza, it left its headquarters in Syria in 2012 after a falling out with President Bashar al-Assad amid growing conflict there. The most common refrain heard among supporters of the ongoing insurgency has been that Syrian rebel groups must unite to topple Assad, a strikingly familiar appeal for the Palestinian national movement. In fall 2012, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared, “It is encouraging to see some progress toward greater opposition unity, but we all know there is more work to be done.”2 Nonetheless, subsequent talks in Doha, Madrid, and Istanbul failed to unite a fragmented opposition. Dueling alliances among numerous political and military groups such as the Syrian National Coalition, the Army of Conquest, and the Southern Front have been formed, although they have had little discernable impact on a conflict that continues to be marked by extensive infighting among rebels and a general failure to remove Assad from power.

Why would Syrian rebel groups that share a common enemy fail to unite when they and their supporters all publicly proclaim that unity is the key to victory? And when alliances have occurred, why have they done so little to lessen the violence and promote victory? Moreover, why would notoriously self-interested organizations ever put in significant effort toward a common goal such as the overthrow of Assad in the first place? Such behavior surely defies our expectations for collective action.

The only actors that may perceive the ongoing stalemate in Syria as a bright spot are the Syrian Kurds and the members of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), who have maintained Kurdish enclaves in northern Syria against Assad and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) alike, with the help of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, PKK) from Turkey and the Kurdish Peshmerga from Iraq. These groups are part of one of the most prominent national movements in the region, which, like the Palestinians, is fighting for a state it does not yet have. Why do the Algerians and Zionists have a state, but the Kurds and Palestinians do not? The Palestinians and Kurds today have more foreign support than the Algerians and Zionists did when they gained independence, and international norms of self-determination and decolonization have never been stronger. All national movements have periods of failure, of course, but it is also worth asking why Algeria and Israel achieved independence in 1962 and 1948, respectively, and not a decade earlier or later.

After spending much of the past eight years researching in archives and conducting interviews with members of the Palestinian, Zionist, Algerian, and Irish national movements, I recognize that the puzzles posed by national movements and political violence today have extensive historical precedents. My analysis of these movements in this book and the presentation of a new theory of violence and victory will provide answers for the past, present, and future.

National Movements: Definitions and Scope

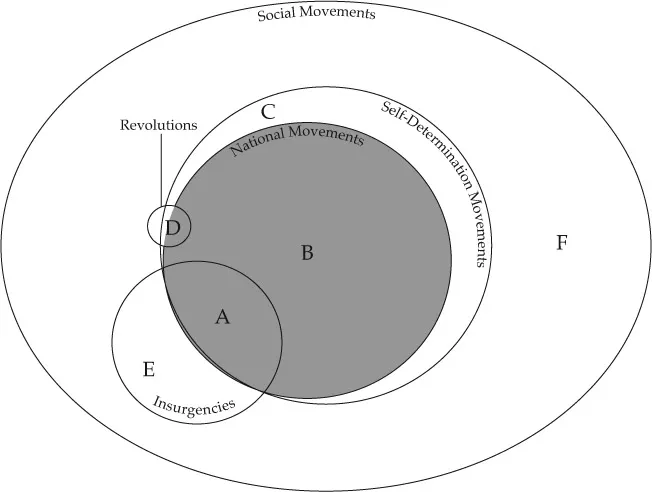

National movements go by many names across the fields of political science, sociology, economics, and history: social movements, self-determination movements, insurgencies, and revolutions. All these concepts are sometimes labeled rebellions and their members rebels.3 Although the terminology is often different, the entities are similar. All involve organizations and individuals struggling to alter the leadership or policies of a state, and all face the challenges that come with attempts at contentious collective action. As such, they are all types of social movements that possess the four characteristics identified by Sidney Tarrow: collective challenge, common purpose, social solidarity, and sustained interaction (see figure 1.1).4

The theory that I present here thus applies to all movements, insurgencies, and revolutions to a significant extent, but there are some key distinctions among them in identity, tactics, and objectives. National movements are distinct in that their social solidarity is based on national identity and their common purpose is political autonomy. In other words, (1) all members of national movements perceive themselves as part of a collective nation that share a common history, language, culture, religion, and/or ethnicity with ties to a particular piece of territory, and (2) national movements launch a sustained effort to achieve political autonomy to protect the nation and its people.5

Figure 1.1. Comparing Concepts: Movements, Insurgencies, and Revolutions

Social movements—such as the numerous women’s rights movements, labor movements, and environmental movements—exist without nations (figure 1.1, F). There is no reliable count of the untold thousands of social movements in the past century, which include the pursuit of changes in state and class structures and policies along nonnational lines. Nations also exist without movements, as demonstrated by periods when the Gauls, Québécois, and Jews were not represented by an active movement for independence. National movements (figure 1.1, A and B), such as those of the Palestinians, Kurds, and Irish, exist at the nexus of identity and action; Bridget Coggins identifies 259 national movements during 1931–2002—and they are all social movements.6

Insurgencies are organized uprisings whose aim is to challenge governmental control of a region or to overthrow the government entirely through the use of force. Insurgencies thus pursue an objective similar to national movements, but they have two key differences. First, insurgencies need not be nationalist (figure 1.1, E). Insurgents can be of the same nation as the ruling regime, as in Cuba in the 1950s or Libya today; or they can hail from multiple nations, as in Ethiopia in the 1980s or Syria today. Second, insurgencies involve the ongoing use of force by definition; national movements do not. Many national movements (figure 1.1, B) are marked by violence at some point, but they also involve civil resistance and periods of peaceful relations with the state, as with the Catalan national movement in Spain today.

Revolutions also need not be violent or nationalist—although they are often one or both (figure 1.1, D)—but their overthrow of the existing political or social order always represents major strategic success by definition and so cannot be identified ex ante (despite the desire of many proponents to do so).7 Jason Lyall and Isaiah Wilson identify 153 insurgencies during 1931–2002, while Jeff Goodwin identifies 15 revolutions during a shorter period, 1945–1989; 54% and 40% of these were nationalist, respectively.8

Self-determination movements (figure 1.1, C) are closest to the concept of national movements that I use in this book, with one small exception. Kathleen Cunningham includes, in her category of self-determination movements, groups that simply want to promote their language and culture—what Eric Hobsbawm would call proto-nationalist movements—whereas the aim of the national movements studied here was to achieve political autonomy and independence.9 For example, the Berbers in Algeria today would be included in Cunningham’s category and study but not in mine because I argue that the dynamics and stakes of pursuing an independent state are significantly different from those of pursuing bilingual education. Still, the claims I make here should largely also apply to self-determination movements, given their significant overlap in cases, and to a lesser but still significant degree they should apply to nonnational insurgencies, revolutions, and social movements.

Why the Use of Violence and the Outcomes of National Movements Matter

Nationalism has arguably been the greatest political force in the world over the past two centuries. As Ernest Gellner and Charles Tilly explain, states existed before nations and helped drive the demand for nationalism by creating a political entity whose profitable, coercive apparatus provided significant private goods to those who captured it.10 National movements subsequently became the greatest challengers to the massive multiethnic empire states that dominated the globe and ruled by the divine right of kings.

After the American and French revolutions and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, nationalism rose across Europe and then played a leading role in the breakup of the Habsburg Empire and the unifications of Germany and Italy, the end of the Ottoman Empire and the redrawing of borders in the Middle East, two world wars and countless regional conflicts that reshaped the international system, decolonization in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, and the breakup of the Soviet Union. Indeed, the great powers—the United States in Vietnam, France in Algeria, and the United Kingdom in India—and supranationalist revolutionary ideologies—Marxism, pan-Arabism, and Islamism—have broken like once-proud waves on the enduring, sharp rocks of national movements.

The end of the Cold War and the era of globalization ushered in a brief period when some questioned the continued relevance of national identity, but nationalism has come roaring back.11 This is nowhere more apparent than in the Middle East, where today numerous national movements exist that lack states, attempt to reshape borders, and push to dissolve the post–World War I order. The nation-state remains the fundamental unit of analysis in international relations and comparative politics. Most scholars of international relations conflate “nation” and “state”; in this book, I analyze when and why the former creates and controls the latter.

Although nationalism has been a force on the march for over two hundred years, individual national movements have experienced a mixed record of success and failure across time and space. Most states in the world today are the result of successful national movements—95 out of 154 new states from 1931 to 2002—but, as Gellner notes, the “number (of potential nations) is probably much, much larger than that of possible viable states.”12 There are over three hundred nations without states today—although many are without robust movements—and only 37% of national movements gained independence from 1931 to 2002.13 Furthermore, each of these successful movements had failed campaigns before its ultimate victory; moreover, most failed movements had successful campaigns before their ultimate (or ongoing) defeat.

The variation in the outcomes of national movements is matched only by the variation in the behavior of their constituent groups. Only 23% of national movements involve no violence, meaning that in most movements there are groups employing and restraining violence despite their shared objective, and the same groups vary in their employment of violent and nonviolent tactics over time.14 In the Zionist movem...