[1]

Organizing Insurgency

Several times in the spring of 2008 I made my way through a set of checkpoints into a Sri Lankan military base in the heart of Colombo. After a motorcycle ride with a security guard, I entered a block of rundown apartments ensconced in barriers, barbed wire, and heavily armed security personnel. Each time I had come to interview a member of one of the Tamil political parties that had opposed the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and that now sheltered behind the simultaneously protective and repressive arms of the Sri Lankan state. Ironically, several of these political parties had their origins as anti-state insurgent groups in the 1970s and 1980s. One by one, organizations such as the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOT) and the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) had been ruthlessly targeted by the LTTE. The LTTE struck these groups when they were internally divided, torn by splits and feuds that made them vulnerable to fratricidal assault. They were then forced into an alliance of convenience with the government.

Though the LTTE was eventually wiped out in 2009, the Tigers’ tight discipline and ability to calibrate and target violence turned them into the ultimate arbiters of Tamil politics and a key influence on Sri Lanka’s politics and economy for nearly a quarter of a century. Groups such as the PLOT and EPRLF, by contrast, were plagued by problems of factionalism that doomed them to a marginal role in Colombo. Organization and power were fused together in Sri Lanka’s long war. These dynamics are not unique to Sri Lanka: whether in Sudan, Pakistan, or Colombia, the ability of rebels to build strong organizations has been crucial to their military effectiveness and political influence.

This book uses a new typology of insurgent groups, a social-institutional theory of insurgent organization, and comparative evidence from South and Southeast Asia to explain how insurgent groups are constructed and why they change over time. The prewar networks in which insurgent leaders are embedded determine the nature of the organizations they can build when a war begins. Preexisting social bases vary in the kinds of social resources they can provide to organizers. Four types of insurgent groups—integrated, vanguard, parochial, and fragmented—emerge from different combinations of prewar networks. This is why insurgent groups that are otherwise similar, with the same ideology, ethnicity, state enemy, and resource flows, often have dramatically different forms of organization.

These initial organizational structures are not locked in place, though they do constrain the likelihood and nature of change. The violence and dislocation of war opens the possibility for major changes in how insurgent groups are organized. Shifting horizontal and vertical ties lead to organizational change, as social embeddedness determines whether insurgent institutions can be built and maintained in the face of counterinsurgency. Starting points create different pathways of likely change: vanguards are more vulnerable to leadership decapitation than parochial groups, for instance, but they are also better able to create coordinated strategies. Insurgents try to build and protect these social ties in order to expand their organizational power, while counterinsurgents try to disrupt them and induce collapse. This struggle is the core battle of guerrilla warfare. The evolution of insurgent groups blends historical legacies from prewar politics with counterinsurgent strategy, insurgent innovation, and international intervention during war. Explaining insurgent organization makes it possible to understand when rebels can generate military and political power and when insurgent challenges instead shatter into factionalism and collapse.

WHY INSURGENT COHESION MATTERS

Insurgent cohesion shapes how wars are fought, how wars end, and the politics that emerge after war.1 The organization of an insurgent group is crucial to its effectiveness in battling counterinsurgents. As Huntington argues, “Numbers, weapons, and strategy all count in war, but major deficiencies in any one of those may still be counterbalanced by superior cohesion and discipline.”2 Organizational control is central to military struggle.3 Insurgent discipline also plays a key role in explaining violence against civilians during war. Undisciplined armed groups are often predatory toward civilians as foot soldiers pursue their own agendas without central control.4 In Iraq, for instance, loose command and control within Moktada al-Sadr’s militia contributed to opportunistic local ethnic cleansing of Sunnis in the aftermath of the American invasion. Disciplined groups, by contrast, may victimize civilians in a more systematic way according to the strategic orders of their leaders. For example, the LTTE engaged in carefully coordinated campaigns of ethnic cleansing made possible by high levels of organizational control, and its cadres stopped this behavior when LTTE leaders told them to. Different patterns of violence are linked to different patterns of organization.

Insurgent cohesion also affects the prospects for peace by influencing negotiations, demobilization, and postwar stabilization. Radical factions create splits that cause “spoiler” problems and undermine deals.5 An organization whose leaders cannot control its fighters is not a credible bargaining partner. Disciplined organizations may be able to avoid unexpected spirals of uncontrolled violence, but fractious groups and movements find themselves torn by patterns of outbidding and competitive violence between prospective leaders that make negotiations fall apart. Keeping a group together during a controversial peace process is difficult and requires powerful mechanisms for maintaining control and unity.6

Insurgent organization further affects state building and regimes after conflicts.7 Integrated insurgents can impose their favored regime once they have seized power, but fragmented groups are prone to destabilizing battles over the spoils of victory.8 Vu, for instance, shows that the structure of insurgent movements determined the nature of state building and economic development in postcolonial Asia. Different political outcomes flow from different kinds of armed groups.9 While insurgents care about achieving a variety of goals—taxing peasants, killing soldiers, pursuing ideological visions—all require some minimum level of control and unity. Armed groups spend enormous amounts of time and energy trying to build or protect cohesion because organization is central to the politics of civil war, state formation, and peace building.

THE LIMITS OF EXISTING EXPLANATIONS

Most research on civil war takes the structure of insurgent groups as a given rather than trying to explain it.10 Research that does offer explanations of insurgent organization can be broken into four broad approaches; these focus on state structure and policies, material resources, ideology, and mass support.11 This is a rich and important literature, but it suffers from important limitations.

State-centric theories argue that insurgent groups are reflections of states and the political contexts they create.12 For instance, Goodwin argues that insurgents will be cohesive when they face weak but exclusionary states, and Skocpol suggests that sustained peasant rebellion will be possible only when the state is suffering a crisis. While these political contexts are undoubtedly important, this approach underestimates the agency and autonomy of insurgents. They can find ways of defying states, overcoming structural constraints, and creating new opportunities. The dramatic differences that frequently emerge across insurgent groups fighting the same state at the same time make it clear that we need to pay more careful attention to the capabilities, social bases, and strategies of these groups.

A more recent wave of research argues that the material resources of insurgents affect how they are organized and how this organization determines behavior. A key claim in this work is that groups built through or reliant upon state sponsors, diamonds, oil, and other natural resources are prone to thuggishness, indiscipline, and fragmentation.13 There are certainly cases that support this argument, but some of the most skilled, resilient, and cohesive insurgent groups in recent history have been fueled by diasporas, state sponsors, drugs, and smuggling, from the Afghan Taliban to the Provisional Irish Republican Army.14 Other groups with the exact same resource endowments have fallen apart. Material resources alone do not determine the success or failure of insurgent groups.15 Instead, other factors determine whether resource influxes will bolster or undermine cohesion.16

A third explanation highlights the mass support that armed groups receive: those with popular support can attract more recruits and greater allegiance along class or ethnic lines than groups advancing an unpopular ideology.17 The problem with this approach is that we regularly see disciplined groups pushing aside more popular rivals and dominating insurgencies and revolutions. Organization and control can trump mass sympathy, as popular support does not seamlessly create institutions for waging war. The challenges of collective action do not make mass support irrelevant, but they do make organization a crucial precondition for taking advantage of popular sympathy.18

Finally, ideology has been advanced as an explanation for organizational structure. During the Cold War, the Leninist “combat party” and the Maoist model of insurgency were both hugely influential in how insurgents thought about organizing themselves.19 Yet it is not easy to convert these blueprints into reality, as many rebels hoping to follow in the footsteps of Lenin and Mao found to their chagrin. Ideas are obviously of great importance, but they need to be turned into durable organizations in very challenging and dangerous circumstances. Insurgent leaders are not unconstrained agents who are able to create whatever organizations they please.20 Thus, we need to identify the circumstances under which ideas can be implemented.

There are three more general problems with existing research. First, these works do not offer careful conceptualizations of how insurgent groups differ from one another, which makes it difficult to study groups comparatively or over time. Second, key existing theories are only loosely related to prewar political life: in this literature, insurgent groups seem to come out of nowhere once wars begin. We need to take history seriously to understand how armed groups emerge. Third, there is little explanation of change over time within war. Some influential variables that are used to explain outcomes, for example the resources available in a particular war zone or a state’s regime type, are frequently static. Insurgent groups often change over time with important consequences, but we lack a convincing account of change. This book tackles each of these three challenges.

ANALYZING INSURGENT GROUPS

The first step in explaining patterns of rebel organization is identifying how insurgent groups differ from one another. An insurgent organization is a group of individuals claiming to be a collective organization that uses a name to designate itself, is made up of formal structures of command and control, and intends to seize political power using violence.21 This distinguishes organizations from movements: Hamas is an organization while the Palestinian national movement is not, and the Taliban is an organization while “the Afghan insurgency,” which combines several organizations, is not.

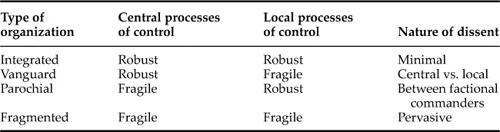

Insurgent groups have central processes of decision making and institution building and local processes of recruitment and tactical combat. Insurgent organizations differ in the strength of these control processes and the patterns of internal politics they create. Four types of insurgent groups can be identified according to how they combine central and local control: integrated, vanguard, parochial, and fragmented (table 1.1). Because groups can move between these organizational types over time, this typology is useful both for comparing groups with one another and for identifying changes within a group.

An organization with robust central control coordinates its strategy and retains the loyalty and unity of its key leaders as it implements strategy. It establishes and maintains institutions for monitoring cadres, creating ideological “party lines” that socialize new members, engaging in diplomacy, and distributing resources. By contrast, organizations with fragile processes of central control experience leadership splits and feuds. Their bureaucracies for socialization and discipline are nonexistent or function poorly, no single voice is capable of negotiating or speaking for the group, and policies are not consistent across factions.

Table 1.1. Types of insurgent organizations

Strong local control processes involve reliable, consistent obedience from foot soldiers and low-ranking commanders. Institutions exist on the ground to recruit and socialize fighters who become loyal to the leadership. Ob...