![]()

PART I

Homogeneity in the People’s Home

![]()

Chapter 1

1928–1932: ETHNIC NATION AND SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION

Sweden’s Social Democratic Party (Socialdemokratiska Arbetarpartiet, or SAP), was founded in 1889, growing out of and primarily backed by the trade union movement.1 The early party had a particularly close, formal association with the blue-collar trade union federation, the Landsorganisation (LO). In its early days, SAP was dedicated first and foremost to revolutionary class struggle. The party initially modeled itself after the German Social Democrats, whose manifesto provided not just the inspiration, but the actual text for SAP’s own first party program. Though some within the party—notably, Hjalmar Branting, SAP’s first elected representative—supported social reform, most were in favor of revolution. Even the supporters of a more moderate program of reform did not dismiss the usefulness of force as a way of bringing about the revolution.

The focus remained primarily on militant class struggle into the early 1920s, but alternate views, more optimistic about the possibility of reforms as an end in themselves, began to surface in the mid-1910s. In 1917, differences of opinion on these two perspectives on reformism led to a split in the party, with the Social Democratic Youth Organization leaving for a new, left-wing socialist party with ties to Russian communism. The loss of the more radical element of the party left room for collaboration with other parties. SAP formed a close cooperation with Liberals in the campaign for universal suffrage and, later, the eight-hour workday. By the time universal male suffrage was achieved in 1918 (1921 for women), a commitment to work within a democratic system had replaced revolution at the heart of SAP’s program.2 As Herbert Tingsten put it, “With each year the party’s perspective shifted a little until … the word ‘democracy’ was accorded the sacred position once reserved for ‘socialism.’ ”3

The cooperation between Liberals and SAP was never entirely smooth. SAP’s desire to retain the classical Marxist view of class struggle, furthermore, prevented the party from supporting many of the Liberals’ preferred reforms. Yet, the coalition remained strong so long as democratic, and not social, reform remained the focus of Swedish politics.4 Cooperation between the Liberals and SAP broke down following the success of the suffrage campaign in 1918, and SAP formed their first government alone in 1920. The reason for the official break in 1920 was, nominally, a dispute over municipal taxes. However, SAP’s desire to pursue the idea of socialization weighed heavily in the decision to break up the coalition. Following this disintegration, the Liberals quickly became the main object for Social Democratic opposition as the Liberals realigned themselves with the Conservatives.

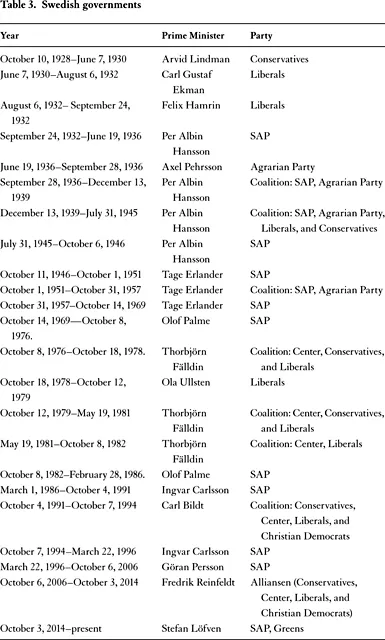

By 1932, SAP had become Sweden’s biggest party, ushering in an era of Social Democratic rule that was unbroken until 1976, and a dominance that continued into the 1990s (for a timeline of Swedish governments, see table 3). Some have credited a shift to “moderate reformism” as the reasoning behind SAP’s breakthrough,5 and others a change in SAP’s concept of democracy.6 Both of these changes probably were important, as were SAP’s attempts to build cross-class alliances with the rural proletariat and smallholders.7 It is also true, however, that SAP’s rhetoric shifted in this time, and the party no longer profiled itself solely as a “working-class party.” Rather, SAP began to claim that it was a party of the whole nation—a folkparti.8

This chapter focuses on the process by which SAP became a national party, and how it began to position itself as the architect of the welfare state. I focus on SAP as a party, rather than welfare-state development, which makes sense given the role that party politics played in creating the Swedish economy and considering that most of the foundations for the welfare state were put into place after 1932.9 It is also worth noting that Gramsci considered the intellectuals’ transition from claiming to speak for a class to claiming to speak for a nation to be a key step in the building of a new hegemony.10 To achieve this transition, SAP drew on ethnic, civic, and mixed ethnic-civic definitions of the Swedish nation. This use of multiple and mixed idioms represents a strategy to solve a potential crisis for the Social Democrats in a context where they are balancing national and class interests. SAP is responding, essentially, to the demand for the working class to be integrated into the national whole, and it achieves this integration through controlling the definition of the nation. SAP’s definitional efforts, were, thus, an expansive response to a crisis of closure-as-access to goods, although one with certain restrictions at the margins. SAP aimed to establish the Swedishness of the nation on partially ethnic grounds, but this strategy turned out to be expansive as a context where ethnicity is more—not less—inclusive than class categories. The party achieved success by providing a set of highly resonant conceptions of the nation, but these were conceptions that privileged SAP and their ideas about the social system.

The Swedish Folkhem

In 1928, SAP’s party chairman, Per Albin Hansson, gave a speech that called on Swedes to treat Sweden as a good home and the Swedish nation as a single family. The folkhemstal was a speech that marked SAP’s separation from revolutionary class struggle, signaling the party’s aspirations to become a national party. In presenting such a cohesive, resonant vision for Sweden’s future, the speech set the tone for SAP’s (and Sweden’s) politics for most of the rest of the twentieth century. Though Hansson did not coin the term “People’s Home,” his use of the term made SAP and folkhemspolitik (people’s home politics) synonymous. But, what, exactly did the concept mean?

The term “People’s Home” historically had a wide variety of meanings. When folkhem was first used is unknown, but the term came into wide usage in connection with a Liberal campaign to extend access to newspapers in the 1890s. The term folkhem as referring to the Swedish nation was of a later mint. Rudolf Kjellén, a political scientist and Conservative politician, is credited for first using the term as such. Kjellén did not give the term a very precise meaning, however, using it generally to represent a strong, traditional national community.11 The Liberals, as well, laid some claim to the term and continued to use it to refer to Sweden throughout the 1920s. For the Liberals, the “People’s Home” was an expression of their specifically democratic conception of the Swedish nation and state. The party tended to use folkstat (people’s state) interchangeably with folkhem, indicating that perhaps the social aspect of the concept was less well-developed among Liberals. The equation of the folkhem with the more complex set of obligations and expectations required in a social state was a wholly Social Democratic innovation. And it was highly successful. As SAP ascended to their place of dominance, the People’s Home idea became entirely bound up with social democracy (and with Hansson personally), eclipsing all previous uses of the term. When Hansson launched folkhem as the organizing principle of a new national Swedish social democracy, he offered some insight into who ought to be a part of the Swedish nation.

The primary image in the speech was one of “the good home,” an image of familial harmony and solidarity. It is that sentiment that underlies the most famous passage of the speech:

The foundation of the home is fellowship and feelings of togetherness. The good home doesn’t admit privilege or backwardness—neither favorites nor stepchildren. There one doesn’t look down on the other. There, one doesn’t seek advantage to another’s cost. The strong do not oppress or pillage the weak. In the good home there is equality, compassion, cooperation, helpfulness. Adapted to the great people’s and citizens’ home this would mean the breaking down of all the social and economic barriers that now divide citizens into the privileged and the backwards, the ruling and the dependent, the looters and the looted.12

Because Swedes were all members of the great Swedish family, Hansson argued, they ought to take care of each other. The People’s Home was rooted in equality, compassion, and cooperation. The familial imagery calls to mind a rhetoric of blood ties that necessitates mutual obligation. Though civic nationalisms sometimes use a language of family—brotherhood, especially—the holistic notion of nation-as-family sounds more like a language of ethnicity than of citizenship. There is more than just a touch of paternalism in the family metaphor, too. In Hansson’s folkhem, the state is a kind of guarantor of happy (and equal) family relations.

But the folk (people or nation) were also, notably, citizens. The state may have been the fatherly guarantor of equality, but citizens were also bound up in a network of mutual obligations and rights. Crucially, the realization of the folkhem was both enabled by, and supportive of, democracy. Hansson reportedly agonized over terminology, unsure of whether “People’s Home” or “Citizen’s Home” (medborgarhem) should be used. Indeed, the speech retained the title “People’s Home—Citizen’s Home” despite his choice of the former.13 The idea of the people as democratic citizens pervaded the speech. Hansson highlighted the requirement that democracy be built on a foundation of actual (not just formal) equality, conditioned on positive liberty, a key social-democratic value: “If Swedish society is to become a good citizens’ home, class differences must be removed, social care developed, an economic leveling occur, working people be given their share in economic administration, democracy implemented and adapted even socially and economically.” Democracy was likewise necessary to ensure equality: “It [was] the major task of a true democratic politics to turn society into the good citizen’s home.” The folk was formulated as a body of citizens, made equal because of their connection to a protective state. Attaining equality, and making the nation into a “good family” was possible, according to Hansson, only with the guidance of SAP as the party of true democracy and the ultimate guarantor of equality. In launching this new politics, what was conspicuously scarce (though not absent) in this speech were references to SAP’s traditional base: the working class.

SAP, from Class to Folk Party

Writing on the anniversary of the founding of a southern branch of SAP in 1931, one Social Democrat celebrated the increasing unity and universality of the party as such:

Like birds, who one by one took off in a storm, they flew against the wind, eventually gathering together in a great flock. That the light fell differently on each of them doesn’t mean that they didn’t take off with the same colors on their wings. They have all borne the colors of social democratic ideals and have had the welfare of the whole nation as their goal (emphasis mine).14

Class-struggle politics, Hansson had realized, would only take SAP so far. To stand on their own, separate from the Liberals, SAP needed to appeal to a broader base. That SAP would reach out to a broader base is not surprising. As mass democratic participation increases, as occurred with the granting of universal suffrage from 1918 to 1921, the need for parties to appeal to the greatest possible number of voters increases. Parties seek to minimize calls to action that would divide the electorate, including calls to class struggle,15 and many “workers’ parties” are actually organized along “peoplehood” lines.16 What is interesting in the case of SAP is, on the one hand, their remarkable success, and, on the other, how they achieved it. That SAP, in Sweden where working-class interests are thought to have been best promoted, was actually working outside the class-struggle frame, is significant.

In general, SAP’s language of class struggle declined, and appeals to the whole nation increased between 1928 and 1932. The language of class never fully disappeared, but the contexts in which it was used became more restricted. In the 1928 parliamentary election campaign, SAP mixed class politics with appeals to the broader folk. Consequently, Social Democrat Gustav Möller declared at the 1928 May Day demonstrations in Stockholm that “the workers stood under the command of a foreign class” and that SAP’s responsibility was first to the working class,17 while in Malmö, Zeth Höglund argued that SAP did not represent solely the working class, but rather “aimed, on the whole, for society’s best.”18 Similarly, the 1928 program not only spoke of an obligation for workers specifically to mobilize and to “battle the true terror” of a nonsocialist regime but also reached out to those who “desire a politics in the spirit and meaning of true societal solidarity.”19

SAP’s claims to be a national party intensified in the 1930 elections. It claimed it was the only party that would, in its “political action, str...