![]()

PART I

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

![]()

[1]

Japan’s Grand Strategies

Connecting the Ideological Dots

Foreign affairs are always and everywhere domestic affairs as well. Japan has been no exception. By enforcing isolation for 250 years, the Tokugawa rulers were required to regulate, and often repress, scientists, Christians, and merchants at home. When regulation failed and the world forced itself upon the shogunate, fundamental differences about how to respond to the Western powers—whether to try to achieve national autonomy or acquiesce to foreign domination—stimulated the 1868 coup d’état that ended the regime. Likewise, five years later, when pragmatic oligarchs blocked Saigō Takamori’s impetuous plans to invade Korea, the result was civil war and consolidation of the Meiji state. Later Meiji leaders repeatedly used foreign adventure to legitimate their rule, proving Japan could be as “normal” as any other state. And it was. Catch-up industrialization combined with catch-up imperialism, and Japan achieved something close to parity with Western powers.

At first Japan took small bites, later big gulps. But its pervasive sense of vulnerability in world affairs was always reflected in domestic politics, not least after Japan’s devastating defeat in the Pacific War. For a half century, contested views of the cold war, expectations for the alliance with the United States, and beliefs about the legitimacy of the Japanese military formed the central divide in Japanese politics. Securing Japan has always been the central axis of Japanese political life, and it remains so today.

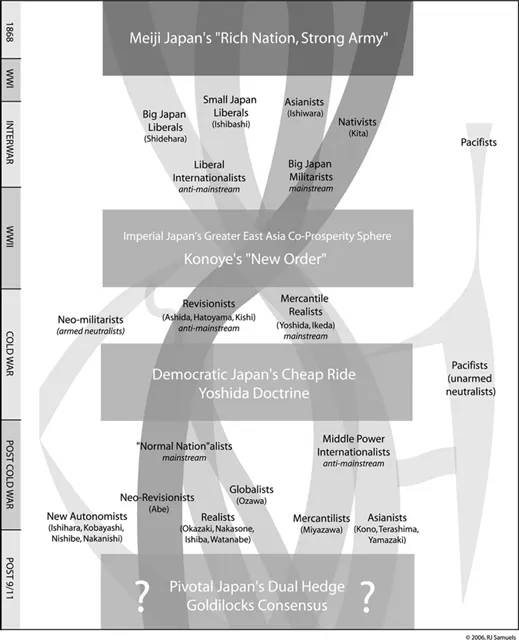

In this chapter I examine the ebb and flow of debates over Japan’s international posture and their importance for domestic politics. I demonstrate how international constraints and domestic politics have interacted repeatedly—across a range of domestic and world orders—to filter and frame security policy choices. Alternating periods of dispute and consensus have engaged the entire national intellect, mobilizing at different times and in different measures liberals, nativists, Asianists, internationalists, militarists, nationalists, mercantilists, globalists, realists, and revisionists. These players have had shifting connections, many extending across the formation of the several new world orders to which Japan has had to adjust.1

Figure 1. Connecting the ideological dots.

Here we seek to connect these “ideological dots”—or at least to sketch them in historical context—to understand both the enduring values that have informed the choices of Japanese leaders and to map contemporary Japanese grand strategy in its fullest context.

The pattern is straightforward. Vigorous—indeed, sometimes debilitating—debate over Japanese security has been punctuated by three moments of consensus since 1868. And a fourth is now under construction. A widespread belief in “catching up and surpassing” the West helped elites forge the Meiji era consensus: borrow foreign institutions, learn Western rules, master Western practice. This “rich nation, strong army” model was a great success, but by the end of World War I, when it was clear that the West viewed Japanese ambitions with suspicion, the consensus had become tattered. After a period of domestic violence and intimidation, a new consensus was forged on a less conciliatory response to world affairs. Prince Konoye’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere attracted support from across Japan’s ideological spectrum. Now Japan would be a great power, the leader of Asia. The disaster that resulted is well known, and from its ashes—again, after considerable debate and creative reinvention—Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru forged a pragmatic path to cheap security. But it was not free. It cost Japan its autonomy, a cost increasingly seen as more than Japan should pay. In recent years, the Yoshida Doctrine that joined Japan at the U.S. hip has been questioned—both by those who support the alliance and by those who oppose it. A fourth consensus has yet to reveal itself, though its contending political and intellectual constituents are clearly identifiable.

The Meiji Consensus: “Rich Nation, Strong Army”

Japan, like most rising powers, had a trying debut on the world stage.2 Its geostrategic environment was constantly in flux. Japanese strategists chafed at how the nation was constrained by unequal treaties. They were uncomfortable with the condescension of Western powers and were determined to achieve equality in world councils. But it was not abstract ideology that animated them. These were realists who fully understood power and who closely calculated its international balance.3 They viewed Russian ambitions in the Far East with suspicion and reluctantly bided their time before extracting advantages from decrepit Chinese and Korean monarchies. Important decisions were deferred until Japan was sure of its own strength. After all, there were—and would continue to be—a great many options. As Taiyō magazine asked on its cover in 1913: “Do we advance to the South or to the North?”4

Strategists spent the first decades of Japan’s industrial modernization sorting this all out before arriving at a Meiji consensus. They would not allow Korea to fall into the hands of a hostile power, Russia’s access to the Pacific would be contained, contiguous territories such as Okinawa in the south and the Kuriles in the north would be incorporated, and technology would be acquired to build a military industry and modernize the nation simultaneously. Autonomy was privileged in a pragmatic strategic vision that subordinated prestige, if only slightly. As Akira Iriye argues: “National independence, treaty revision, and modern transformation were all aspects of the same agenda, that of emulating the powerful and advanced Western nations.”5

The army’s patience was rewarded when the Meiji state began to feed its continental ambitions. Two wars—the first with China in 1895, the second against Russia in 1905—were fought under the banner of Yamagata Aritomo’s 1890 grand strategic doctrine that etched a “line of sovereignty” (shukensen) around the Japanese homeland and a “line of interest” (riekisen) extending into neighboring areas such as Korea and Manchuria.6 In 1907 Yamagata elaborated his blueprint for empire. His Basic Plan for National Defense identified Russia, the United States, and France as potential enemies. The latter two threats were less pressing, best left for the Imperial Navy, which still needed time to grow. Russia was the clear and present danger, and the Imperial Army of twenty-five standing divisions would confront it.7

Japanese leaders proved repeatedly that they could confidently step onto the international stage to alter the status quo and earn the indulgence (if not the respect) of the great powers in doing so. In 1876 Japan subjected Korea to its influence by “opening” it with impunity. Japan defeated Qing China in 1895 to gain significant concessions, and shortly thereafter, in 1900, Japan contributed twenty thousand troops—nearly double the contingent of any other nation—to a multinational force that crushed the Boxer Rebellion. Japan was rewarded in 1902 with an alliance with Great Britain, the world’s greatest maritime power, and soon thereafter defeated their common threat, Russia, in modern warfare.

By the time this first wave of adventure had subsided, Japan had increased to include southern Sakhalin, southern Manchuria, Taiwan, and Korea. To some in Western capitals it seemed that Japan had begun overreaching, and Japanese military gains were rolled back. Treaties at Shimonoseki in 1895 and Portsmouth in 1905 were object lessons about international politics: Japanese strategists thought they had coordinated their national ambitions with the great powers, but the West did not agree with Gen. Tanaka Giichi that Japanese claims on the continent were “heaven-given.”8

On the eve of World War I, domestic politics were unsettled, but Japan was already a rising industrial powerhouse that believed dominance of the continent would dampen domestic unrest. Yamagata and Tanaka, his deputy, welcomed war in Europe as an opportunity to develop an “autonomous” military program. They would “ally” with China and push Westerners out of Asia.9 Some civilians agreed; other no less ambitious proponents of Japan’s continental interests insisted that greater benefit would come from cooperation with the allied powers. Foreign Minister Katō Takaaki, a future prime minister (and Yamagata’s chief antagonist), played a balance-of-power game that aimed to keep Russia out of Manchuria by maintaining relations with Britain. That meant declaring war on Germany. There was no consensus, even within the military. The Imperial Navy distanced itself from the army’s objectives. Ultimately, the Japanese government sided with the Allies, helped expel the Germans from Asia, and rubbed its hands in anticipation of the gains that would be showered on it.

And some were. Because the wa...