CHAPTER ONE

THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE AND BURMA

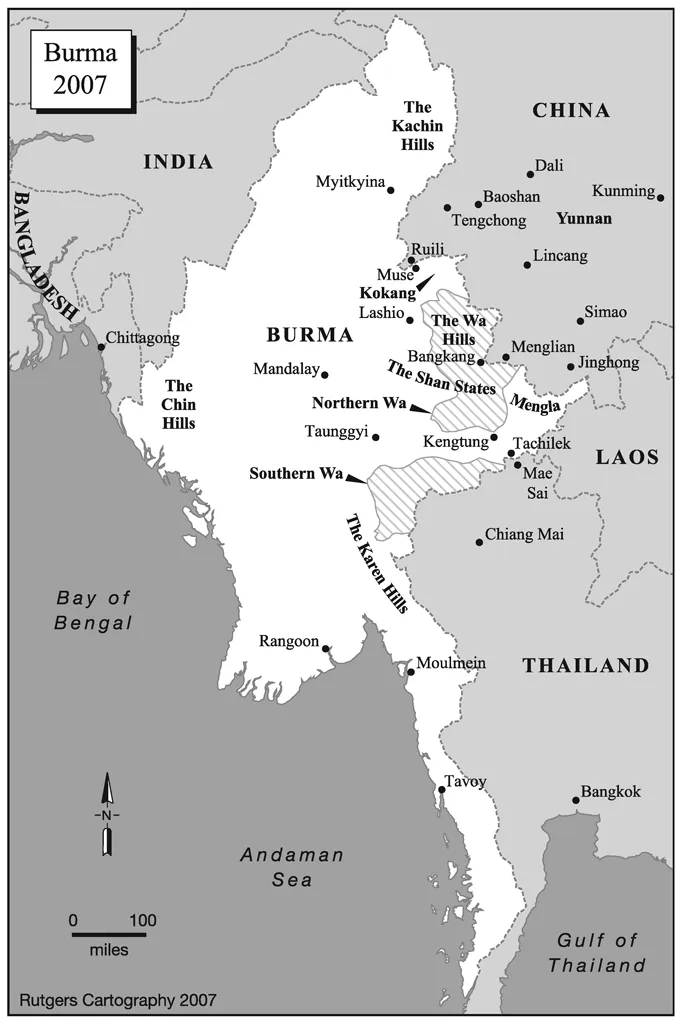

One of the world’s major opium cultivation and heroin producing areas is the Golden Triangle, a 150,000-square-mile, mountainous region located where the borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand meet (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2006). In the 1990s, it was estimated that Burma produced more than 50 percent of the world’s raw opium and refined as much as 75 percent of the world’s heroin (Southeast Asian Information Network 1998). During that time, Burma was also the largest source of heroin for the U.S. market, responsible for 80 percent of the heroin available in New York City (U.S. Senate 1992; Gelbard 1998). In the late 1990s, hundreds of millions of methamphetamine tablets were produced annually in northeastern Burma and smuggled into Thailand for the booming Thai market (Phongpaichit, Piriyarangsan, and Teerat 1998; Chouvy and Meissonnier 2004).

The major opium growing area in Burma is located in the biggest and most populated state, the Shan State, occupied by various ethnic armed groups (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2005a). The Wa, one of the largest of these ethnic armed groups, is in control of an area referred to as the Wa State, or Burma Shan State No. 2 Special Region, which produced 60 percent of the opium in the Shan State in the late 1990s (Lintner 1998a).1 According to the United Nations’ 2005 Opium survey in Burma, “94 percent of total opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar took place in the Shan State and 40 percent of national cultivation (or 42% of Shan State cultivation) in the Wa Special Region” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2005a, 3).

Shan State provided a base for the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) before the party collapsed in 1989, when leaders of the Wa area and of Kokang (another area in the Shan State that is dominated by an ethnic Chinese armed group) announced their independence from the CPB (Lintner 1990).2 According to the Burmese government, the CPB, which had strong support from China and various non-Burmese ethnic groups, was a major threat to its authority (Smith 1999). After the disintegration of the CPB, the Burmese government quickly arranged cease-fire agreements with former CPB groups in the Shan State. The ethnic groups promised not to fight against the Burmese government and, in return, the Burmese authorities allowed these ethnic groups to keep their arms and to remain involved in the opium trade (Steinberg 2001). U.S. sources estimated that Burma’s opium production rose from 1,250 metric tons in 1988 to 2,450 metric tons in 1989 and continued to increase thereafter, to 2,600 metric tons in 1997 (Lintner 1998b). Opium production in Burma began to decline significantly after 1997, and by 2003 it had been reduced to 484 metric tons, according to U.S. estimates, and 810 metric tons, according to the UN opium survey (Jelsma 2005). A subsequent UN opium survey found that opium production in Burma had continued to decline, to 370 metric tons in 2004 and 312 metric tons in 2005 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2005a).3 Interventions (mainly suppression and crop-substitution programs) by local authorities, the Burmese government, and the United Nations; years of unfavorable weather conditions; and the loss of U.S. and European markets were all cited as reasons for the dramatic decline of opium production in Burma (Jelsma 2005). Even so, Burma is still ranked as the second-largest producer of opium in the world, after Afghanistan (Labrousse 2005; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2006).

As opium and heroin production in the Golden Triangle began to take a downward turn in 1997, a year after the surrender of Khun Sa (a drug lord who symbolized the drug trade in the Golden Triangle for de cades) to the Burmese government, the explosive growth of the manufacturing of meth-amphetamine pills in the area during the late 1990s and early 2000s raised doubts in the West over whether the Golden Triangle would ever be able to transform itself into a drug-free zone. Methamphetamine pills produced in Burma began to saturate the Thai drug market in the late 1990s, and the use of the pills began to spread from bus drivers and laborers to students and young professionals (Chouvy and Meissonnier 2004). New towns were built along the Thai-Burma border, allegedly by drug money, to promote the drug trade. Tensions between the Burmese and Thai authorities along the border began to mount, and border clashes occurred when one side thought that the other side was intruding into its territory. The stability of the region was seriously undermined by the massive production of methamphetamine (Dupont 2001). Today, there is no sign that the methamphetamine trade is going to follow opium and heroin production and begin to fade away; this is the one business that businesspeople and political leaders in the area desperately need to offset the economic loss caused by the decline in opium and heroin production.

Burma: A Country in Turmoil

Burma is bordered on the north and northeast by China, on the east and southeast by Laos and Thailand, and on the west by Bangladesh and India. Its coastline runs along the Andaman Sea to the south and the Bay of Bengal to the southwest. Its total area is 2.6 million square miles (6.77 million square kilometers). “Burma is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world. Ethnic minorities make up 30 to 40 percent of its estimated 52 million population, and occupy roughly half the land area” (Kramer 2005, 33). The main ethnic groups are Burman, Kachin, Kayin (or Karen), Kayah, Chin, Mon, Rakhine, and Shan (Ministry of Information 2002). Burman, the majority ethnic group, constitutes about 70 percent of the whole population. Almost 90 percent of the population is Buddhist (Hla Min 2000). The capital of Burma was Rangoon (or Yangon) before the authorities moved the capital to Naypyidaw, an up-country site near the town of Pyinmana in Mandalay State in November 2005.

Burma was colonized by the British and became annexed to India in 1886, and it was briefly occupied by the Japanese during World War II (Thant Myint-U 2001). After the war, the British administration was reestablished in Burma. On February 1947, Aung San, a charismatic Burman leader, concluded the Panglong Agreement with Shan, Kachin, and Chin leaders that laid the foundation for the establishment of a union of equal states in Burma (Elliott 1999). Unfortunately, in July 1947 Aung San and several other prominent leaders were assassinated as they assembled for a meeting in Rangoon. After gaining independence from the British the following year, the country began to disintegrate as many ethnic groups became disillusioned with a central government that was dominated by the Burman (Callahan 2003).

Only three months after independence, the first battle between the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and government forces broke out and fighting soon spread throughout central and upper Burma (Lintner 1990). In the meantime, many insurgencies sprang up around the country as various ethnic groups also began to fight the Rangoon government (Smith 1999). In 1949, soldiers from the armies of the defeated Kuomintang (KMT) entered Burma from China’s Yunnan Province. The arrival of KMT armed groups had a crucial, long-lasting effect on the region (Cowell 2005):

At Burma’s independence in 1948, the country’s opium production amounted to a mere thirty tons, or just enough to supply local addicts in the Shan states, where most of the poppies were grown. The KMT invasion changed that overnight. The territory they took over—Kokang, the Wa Hills and the mountains north of Kengtung—was traditionally the best opium growing area in Burma. Gen. Li Mi persuaded the farmers to grow more opium, and introduced a hefty opium tax, which forced the farmers to grow even more in order to make ends meet. By the mid-1950s, Burma’s modest opium production had increased to a couple of hundred tons per year. (Lintner 1994b, 116–17)

On March 1, 1962, Prime Minister U Nu was ousted after a coup masterminded by a group of army officers led by General Ne Win, a career soldier who played a key role in the anti-Japanese resistance movement during World War II and in the suppression of insurgent ethnic groups after independence (Thant Myint-U 2006). “On the following day, the federal 1947 Constitution was suspended and the bicameral parliament dissolved. . . . Burma’s fourteen-year-long experiment with federalism and parliamentary democracy was over” (Lintner 1994b, 170). After the coup, the Revolutionary Council was formed to implement many new policies to change Burma from a relatively liberal state into a uniquely Burmese socialist state. The Revolutionary Council formed the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) in 1962 and announced its philosophy in “The Correlation of Man and His Environment” in the following year, which provides philosophical underpinnings for the “Burmese Way to Socialism,” an “inward-looking development strategy with emphasis on self-reliance, isolation and strict neutrality in foreign policy. Foreign direct investment was barred” (Collignon 2001, 87–88).

Mixing European socialist policies with Chinese Communist strategies, the Revolutionary Council began to implement dramatic policies that would eventually drive out of Burma the Indians and the Chinese, the two ethnic groups that dominated the Burmese economy. First, in February 1963 the Revolutionary Council nationalized many economic enterprises (Marshall 2002). All business firms, including many small private companies, were taken over by army personnel, and within a couple of years most of these businesses were forced to shut down because of mismanagement, embezzlement, and poor performance. Second, the regime devalued 50 and 100 kyat banknotes without compensation; the intention was to remove wealth from foreign hands. After these two policies were put in place, a large number of Indians, many of them key entrepreneurs in Burma, were expelled to India by Burmese authorities (Fink 2001). In 1967, when the Cultural Revolution was at its peak in China, clashes between Chinese Red Guards and Burmese students in Rangoon resulted in a nationwide anti-Chinese movement; by the time it ended, many Chinese had been killed or assaulted and their houses looted and burned. As a result, tens of thousands of Chinese left Burma for either China or Taiwan (Thant Myint-U 2006).

The following year, China drastically increased its support for the CPB insurgency. Several key insurgent leaders who were trained in China crossed over into Burma, took over many border towns, and set up their headquarters. A large number of young Chinese intellectuals (zhiqing) also voluntarily came to Burma to support the CPB. Many of them are now top leaders of the Wa, the Kokang, and the Mengla governments.

After the departure of Indian and Chinese businesspeople, Burma’s economy began to falter. The establishment of Communist-style cooperatives also depressed the economy and helped to develop a vast black market where the rich still brought what they wanted by paying much more than was paid in the state-controlled stores (Fink 2001).

After the 1962 coup, in order to fight against insurgent ethnic groups in the remote areas, General Ne Win’s Rangoon-based socialist government formed a number of local home-guard units called Ka Kwe Ye (KKY):

The plan was to rally as many local warlords as possible—mostly nonpolitical brigands and private army commanders—behind the Burmese army in exchange for the right to use all government-controlled roads and towns in Shan State for opium smuggling. By trading in opium, Burma’s military government hoped that the KKY militias would be self-supporting. (Lintner 2003, 256)

Many KKY leaders later became some of the most influential figures in the drug business.

From the time of coup in 1962 until 1988, Burma was wracked by armed conflict between the Rangoon government and militant ethnic groups. On several occasions, the rebel groups were poised to take over Rangoon. The Rangoon government also clashed frequently with students who participated in street protests against the government. In 1988, a brawl in a teashop in Rangoon between students and local youths turned into massive, antigovernment street demonstrations led by college students (Steinberg 2001). The Rangoon government reacted violently: many students were gunned down and thousands were arrested, and all universities, colleges, and schools were closed. However, large-scale street demonstrations continued to spread to other cities and towns, and soon the entire country was shaken by daily demonstrations. According to a friend I interviewed in Rangoon: “Nineteen eighty-eight was the best chance for the people to overthrow the military junta; once the chance was gone, people just lost any hope of getting rid of them.”4

Ne Win resigned as BSPP chairman and in September 1988 the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) was formed to shore up the regime. The pro-democracy movement established the National League for Democracy (NLD) and Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of the late Aung San, was named as general secretary (Fink 2001).

In March 1989, a mutiny broke out in the CPB in the Kokang area, and a month later rebellious Wa troops captured its Bangkang headquarters, ending the forty-one-year Communist insurgency in Burma (Lintner 1990). The CPB’s ageing leadership fled to China. Luo Xinghan, a Kokang Chinese who was known as the King of Opium, was asked by the Burmese authorities to initiate a cease-fire agreement. Not long after, Khin Nyunt, then head of Burma’s military intelligence, visited the Kokang and the Wa areas and cease-fire agreements were signed between the regime and the two former CBP groups (Cowell 2005).

Under pressure from the international community, the SLORC conducted a multiparty general election in 1990. The NLD won a landslide victory and captured about 60 percent of the vote—and 392 of the parliamentary seats, including all fifty-nine seats in the Rangoon Division. The military-backed National Unity Party won only ten seats. However, not only did the SLORC refuse to turn over power to the NLD but it also begin to round up NLD leaders. The SLORC had put Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest in 1989. People in Burma were again deeply disappointed with their government and their hopes for reform were completely crushed (Taylor 2001).

The regime worked to consolidate its power:

In the years following the 1990 election, Burma’s generals focused on four objectives. First, they sought to expand greatly the size of the armed forces in order to be in a stronger position against their armed and unarmed opponents. As a result, the number of soldiers was increased from 180,000 in 1988 to over 400,000 by 1999 and new bases were constructed throughout the country. Second, the ruling generals worked to break up the organizational structure of the pro-democracy movement and particularly the NLD. Third, they attempted to neutralize the ethnic nationalities by making cease-fire agreements with almost all the armed groups. And fourth, they tried to improve the economy by opening up the country to trade and foreign investment. (Fink 2001, 77)

In November 1997 the SLORC renamed itself the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), presumably to project a softer image. However, things have remained the same in Burma since the military coup in 1962. When I visited Burma in December 1997, my first trip back to the country I had left thirty years earlier, it was as if I had never been away. Nothing had changed over the past three de cades, except that some of the roads and buildings were in worse shape than before and the city now became a ghost town after dark because of a combination of curfew, repression, and shutting down of nightlife.

I visited Burma again in July 2002 to interview Burmese government and law enforcement officials. The situation then was worse than 1997 because the kyat, the Burmese currency, had taken a nosedive after border clashes between Burma and Thailand in 2001.5 Inflation gripped the country. The unemployment rate was high and many people I talked to were extremely unhappy with the regime. A waiter in a Chinese restaurant told me he was making 8,000 kyat ($32) a month. He said waiters in small coffee shops made significantly less, about 3,000 kyat ($12) a month. He also said the only good jobs in Rangoon were for those who were well connected.

On October 20, 2004, General Khin Nyunt, sixty five, was forced to resign his dual posts as prime minister and chief of military intelligence. Burmese army chief Maung Aye was reportedly not in favor of granting too much autonomy to the United Wa State Army (UWSA), while Khin Nyunt was said to have had very close ties to it (Tasker and Lintner 2001). By coincidence, I visited Muse, a Burmese town right across from Ruili, China, several days after the removal of Khin Nyunt and when I passed by the military intelligence office there, it had already been shut down. Local people told me this was once a place no ordinary citizen wanted to go near and now it was just an abandoned building. After Khin Nyunt w...