eBook - ePub

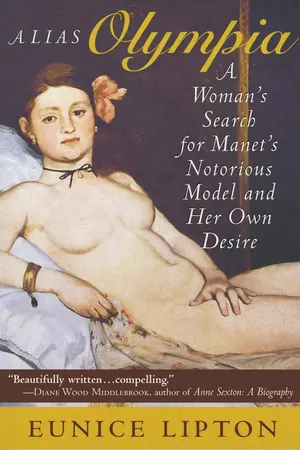

Alias Olympia

A Woman's Search for Manet's Notorious Model and Her Own Desire

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Eunice Lipton was a fledging art historian when she first became intrigued by Victorine Meurent, the nineteenth-century model who appeared in Edouard Manet's most famous paintings, only to vanish from history in a haze of degrading hearsay. But had this bold and spirited beauty really descended into prostitution, drunkenness, and early death—or did her life, hidden from history, take a different course altogether? Eunice Lipton's search for the answer combines the suspense of a detective story with the revelatory power of art, peeling off layers of lies to reveal startling truths about Victorine Meurent—and about Lipton herself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alias Olympia by Eunice Lipton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Biografie nell'ambito delle scienze sociali. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Voilà Victorina

It was a good fifteen years before I embarked on my search for Meurent’s life, but in the mid-1980s I went to Paris for six months and began. It was a casual inquiry, at first. So much so that I didn’t know I was looking for her precisely. The book I had come to work on was call, “Both Sides of the Easel: Women as Models, Women as Artists.” It was going to be about Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Suzanne Valadon, and Victorine Meurent, four women who had been painters as well as models for other artists. I was fascinated by this mixture of traits—that on the one hand each woman coveted the conventionally masculine persona of artist, but on the other, each agreed to the typically feminine role of object. Women traditionally were models and muses, wives and mothers, not artists and geniuses. I thought it would be fascinating to watch two such competing impulses in the same woman and in women of different classes.

Morisot (1841–1895) was an obvious choice, despite the fact that I didn’t much like her work. She was an ambitious artist and a beautiful woman whom Manet relished painting. Like the other Impressionists, she specialized in domestic and bucolic scenes, but her style was instantly distinguishable by its long brushstroke, her taste for white, and her preference for images of women and children. Her accomplishment—both as an artist and as a participant within the Impressionist group—combined with her having in Eugène Manet, the famous Édouard’s brother, an adoring, supportive husband made her attractive to me. She was also a wealthy woman, which cast an interesting light on the question of ambition.

Manet made a number of extraordinary paintings of Morisot during the late 1860s and early 1870s, one of which is Berthe Morisot with a Bunch of Violets. In it the artist portrays a disheveled thirty-one-year-old Morisot averting her gaze from the viewer. Her somnolent black eyes and tenderly pursed pink lips intrude upon the egg-shell delicacy of her face with the most delicate affection. She is as sexy as an unmade bed, simultaneously sheathed and adorned by the deep and decorative blacks of her garments: a tumble-down black hat perches on her straying auburn hair; a black scarf caresses her throat; a black coat sits gently on her shoulders.

A love portrait if ever there was one. And typical of Manet’s pictures of Morisot. She is always represented by him as a beautiful woman languishing on couches or gazing melancholically out at the viewer.

Cassatt (1845–1926) appealed to me more than Morisot because I really enjoyed her work. She, too, was a rich and ambitious woman involved with the Impressionist group, and she chose to model for Degas on a number of occasions. I admired Cassatt’s blunt and elegant adaptation of Japanese prints, and I savored her edginess and wit, her obstreperous children squirming and misbehaving, the trenchant looks of her matronly women. Sometimes—and outrageously—Cassatt silences her feminine sitters by ironically placing teacups and letters over their mouths (Five O’clock Tea and The Letter). Her rambunctious imagination attracted me.

Degas liked to draw Cassatt at her dressmaker’s and milliner’s, gazing in a mirror, turning this way and that to admire a hat, being fitted for a dress. Twice he drew her stylish silhouette in rapt attention in the Louvre. Both depictions, as laconic and witty as Degas can be, show Cassatt engaged in passive and typically feminine pastimes. Only once, in Miss Cassatt Holding Cards, did he evoke an abrupt and inquisitive woman.

From the start my interest was most piqued by Valadon and Meurent, perhaps because I identified with them the most. Valadon (1867–1938), whispered at the edges of Art History, shut away like a madwoman in the attic; writers liked her less than Morisot and Cassatt. She was a favorite model of Puvis de Chavannes, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Renoir, all of whom painted her naked, dancing and waiting—a winsome, seductive girl full of sensuous appetite.

Valadon was a remarkable artist who looked at the underside of life. She drew and painted the sexual awakenings of children, and female nudes that are so awkward and self-contained that they dare the viewer to find his usual pleasures there. Her portraits and still-lifes are positively iconic in their stillness and concentration. I was extremely curious about how this lower-class woman handled her two personae.

Finally, there was Meurent, the most famous face and body of the nineteenth century, painted by Manet, and perhaps by Alfred Stevens, Puvis, and Degas as well. And she was also an artist, although no one had ever laid eyes on her paintings.

A realization that may well have been the catalyst for “Both Sides of the Easel” was the fact that although all four women entered the profession of artist, none were ever depicted working, even by their male artist friends, whereas the men loved to paint each other painting. Examples include Frederic Bazille’s Studio on the rue de la Condamine, Renoir’s Monet Painting in His Garden at Argenteuil, Manet’s Monet Working on His Boat in Argenteuil, and Gauguin’s Portrait of Vincent van Gogh. This omission said: History will turn a blind eye to aberrant desire.

When I heard from an acquaintance who served on a grant-giving committee that I would receive a large grant for the following year to work on “Both Sides of the Easel,” I gave myself permission in the remaining months I had in Paris to focus on Meurent. It was an impulsive decision. I said to myself, “Look, so little is known about her, just go ahead and get all the research done now. You’ll be back next year to work on the real book.” But I never got the grant, and I chucked Cassatt and Morisot. I had to admit, finally, that, however fascinated and outraged I was by their predicaments, their wealth and privilege bored me. Valadon was intriguing/ but I knew a smart woman who was already working on her. Meurent was to be my subject.

Even now as I write her name, she draws me into a state of wonder and reverie. She looks at me wistfully and brushes the hair from my face. She whispers in my ear and hints at marvelous discoveries. She smiles. Then, straightening up a bit she says, half tease, half entreaty, “Find me, Eunice.” How, Victorine?

Will I follow you down the street a hundred years after the fact? Find out where you lived and climb your staircase, touch the walls you touched, imagine you? Must I turn Paris into the site of my unconscious and play it, free-association-style, as if I were lying on a psychiatrist’s couch? Or will it be more tawdry still, like the night a dark young man and I picked each other out on Broadway, prowled the street up and down until moving closer we looked into each other’s cold eyes, and walked back to my apartment?

Victorine tells me of a party in a house set back behind a wall. She says it starts late. I make my way to the designated neighborhood. The trees, gate, silence have all the markings of wealth—where Morisot might live, or Natalie Barney, but not Meurent. I reach the address. The door is open and swings into a spacious, empty entrance way. Candlelight flickers against the wall. Coats and capes and shoes and bags have been dropped on the tiled floor or thrown over chair arms. I find my way behind the foyer to a large room. People are relaxing on plush carpet, on divans, on chairs. Some linger outdoors on balconies facing dark, leafy trees and inky passageways. A beautiful, dark-haired woman looks at me from a couch.

I live in Paris with Ken, my husband, who is a tall, lean, redheaded man, nine years younger than I. At the moment of this story, he’s a painter and a locksmith; he’s not changing anyone’s locks in Paris though. Ken’s hair gently waves, his beard is shaved close, his eyes are a ruddy brown. He has high cheekbones, and a longish nose. Old Russia is written on his face; he’s Vronsky, Alyosha, and even Ivan all wrapped up in one. Ken is one of those handsome men who don’t know it. He is also a deeply private person whose kindly, smiling face could fool you. He’s much more self-absorbed and detached than you’d think. I like the distance, and have many pictures of him from the back, or the side—painting, changing a lock, talking on the telephone.

Ken is wondering how to be a full-time painter, I am eager to walk the city and be alone. We live in the Fifth Arrondissement in two small rooms seven stories above rue Monge.

The search for Victorine is slow. There are days when it’s easygoing and full of pleasure, and others when I bog down in paralysis and nausea. The journey always starts with the endless descent to the street. Sometimes that entry is a long sweet slide into an old familiar dream, and it’s my father saying, “Ah, Paris, that’s where you have to go, Eunie. It’s the most beautiful city in the world—the streets and the lights and the river Seine. Everyone spends their days in cafés talking about interesting things and sipping coffee. Or they sit by the river and read Zola. That’s a city for you.” If the day starts this way, then everywhere I turn will be magic with possibility and the heat of my father’s desires. But other days are bleak; a cold, bloodless woman hovers nearby sneering derisively at me. Her message is, “Better stay home today, dearie.” I often do.

At the beginning, a good day finds me confidently heading to the Bibliothèque Nationale. The Métro drops me at the Palais-Royal, just a few blocks from rue Richelieu and the library, and that’s where I meet my first temptation. Do I take the streets briskly, arriving in five quick minutes at my destination? Or do I choose the Palais-Royal garden route? I can’t resist the garden—the blood-red roses, the silver statues, the history. Especially the memories of Colette high up behind one of the merry striped awnings. And then, depending on my mood, I can or cannot forgo the calming rhythm of the arcades or the conjuring of eighteenth-century revolutionary uproar—prostitutes, journalists, noblemen, and bourgeoisie thrown into unexpected intimacy. Sometimes I daydream in front of an antiquarian’s display. Could Victorine’s paintings…? At the end of the garden I look through the windows of the restaurant, Le Grand Véfour, and imagine Ken and me dressed up, him tall and elegant in his white silk suit, me urbane and pensive in my cool black dress. Now we’re being greeted by the maître d’. Now we’re being seated respectfully among the baroque bric-a-brac and the flower-bedecked mirrored ceiling. Under the table, Ken finds my hand.

The initial research on Meurent is very satisying. I give myself a lot of leeway, permission to dally through material, to linger without knowing why. I’m searching for any clues that will let me sketch a new picture, anything that will distinguish Meurent from the tragicomic cartoon figure drawn by the Art History literature. I find my place in the Cabinet des Estampes, the art room at the Bibliothèque Nationale, take it daily, and read what little exists in the Manet biographies and other artists’ memoirs. Near the beginning, however, I have a nightmare that stops me in my tracks.

In the dream I am working happily away in a place that reminds me of Venice, and in a building like the Frick Collection or the Duke Mansion on Fifth Avenue, where I went to graduate school. I am far up above a marble staircase past a balcony in a large room with long tables. I am alone. My table is full of big open art books, but there is no crowding. Then I am called below; there’s a message for me. Lightheartedly, full of such deep contentment, I start to descend. But no sooner am I out on the balcony and heading down the steps than I notice a fair-skinned, dark-haired, very dark-browed woman in a Kelly green suit. The lines of her brows go straight across her face. She stands quietly, to the side of a tall glass case. My body goes cold. But I continue down the staircase. I pass a statue of a very slim man from the eighteenth century—tight clothes, insinuating gestures. I pick up the message below and come, this time very slowly, up the stairs. At the landing I stop where the statue is. He begins to talk to me. I don’t want to talk. He insists, and I force myself. He gestures too much with his long arms and fingers. I hate him. Finally I leave, and even more slowly ascend the remaining stairs. At the top, the dark-browed woman steps forward. I try to run…scream. But I can’t. I fall into a swoon. The statue, just behind me now, grabs my shoulders, the woman, my legs; one of them—I think the woman—touches my vagina, and I die.

Next morning I can’t get up. Sunk deep into the pillows, I sleep on and on into the day. Finally, I have some coffee, but I read all day in bed. Ken wonders what’s happening. “Oh, nothing,” I say. “I need a little inspiration. I’m just going to read today.” At dinner I try to convince him that we should go away for a few days. I tell him we need a vacation, a fuel-up before we really get started. He says, “Eun, are you kidding? We’ve only been here a week.”

I see his point. Also, I’ve had dreams like this before. They began when I started writing seriously in my late twenties. They come when I am starting a project, and always at the particular moment where there is no turning back.

I return to the library. I call for archival material instead of books. Most important are Manet’s papers—his letters, notebooks, accounts, invitations to his memorial, and so on. Maybe I’ll find a note he wrote to himself about Meurent, a desire to reach her for some reason. Or a piece of gossip about her that he told someone else in a letter. Maybe a notebook reference to her artistic aspirations. I turn over each letter, each notebook page, savoring the transgression of perusing private words in a public space. But I find no reference to Meurent except the address of a “Louise Meuran” in one of Manet’s notebooks. I presume that’s her; Victorine’s middle name was Louise. No mention of her in letters, nothing among the material from Manet’s memorial dinner. She either was not invited, or she decided not to sign the book. Undoubtedly the former; women weren’t invited to such events. Indeed, only men left their signatures. Meurent’s relationship to Manet was as a model—we know that—and one whom he had depicted only nine times. Yes, it was said that she painted a little, but why expect an invitation?

Here’s why. Meurent’s name had been known as early as 1862 when Mane...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgments

- History of an Encounter

- My mama told me…

- Voilà Victorina

- In America

- The End

- Notes