![]()

CHAPTER 1

Low-Cost Competition in the Airline Industry

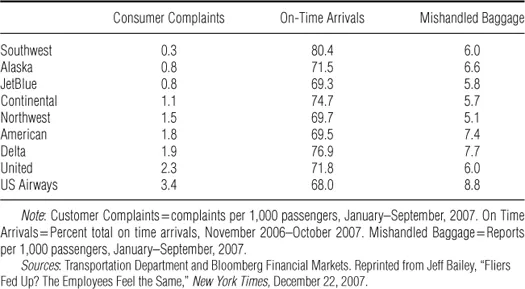

These words from a front-page story in the December 22, 2007, issue of the New York Times should serve as a wake-up call to all those responsible for America’s air transportation system: “And you thought the passengers were mad…. Airline employees are fed up, too—with pay cuts, increased workloads and management’s miserly ways, which leave workers to explain to often-enraged passengers why flying has become such a miserable experience.”1 The story goes on to report comments from US Airways’ employees in a question-and-answer session with their chief executive officer. The employees’ frustrations came through loud and clear about working for the airline with the most passenger complaints and mishandled bags and the lowest rate of on-time arrivals:

“I hate to tell you but the interiors of our planes smell bad and they are filthy. As an employee I am embarrassed to admit working for U S Airways.”

“How long do you think the airline will be around the way it’s running right now?”

Something is fundamentally wrong when both an industry’s workforce and customers report high and rising frustration with the way they are being treated. Can’t the industry do better than this? Is it too much to expect the airline industry, or any other industry for that matter, to provide a fair return to investors, high quality and reliable service to their customers, and good jobs for their employees? Measured against these three expectations, US Airways is not alone. The U.S. airline industry is failing. In the first five years of the twenty-first century, U.S. airlines lost $30 billion. Four of the largest airlines wiped out their equity investors by going into bankruptcy. In 2008, there were only a few airlines in the world other than those owned by governments whose debt ratings put them above junk bond status. These few included Southwest, Qantas, and Lufthansa. In those five years, U.S. airlines also cut wages by more than $15 billion and laid off one hundred thousand workers. Worker morale fell to all-time low levels. And customer complaints rose to record levels as companies cut the number of flights to fill planes and cut services and frills to save money. With all of this, as well as aging air traffic control technologies, labor problems with and shortages of air traffic controllers, and increased congestion and flight delays, industry commentators in the United States and overseas have expressed worries that a “perfect storm” may be coming.2

Is all of this the unavoidable consequence of the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, D.C.? To some extent, yes. The sharp drop in air travel after 9/11 made one-time losses and cutbacks inevitable. But it’s more than that. This upheaval of losses, layoffs, wage cuts, and bankruptcies echoes previous periods in the early 1980s and early 1990s, highlighting the volatile nature of the industry. Booms are followed by contentious battles about wage increases, which are then followed by busts, accompanied by wrenching episodes of restructuring and concessions, which are followed by booms, as the cycle starts again. By 2006, as some U.S. airlines began to eke out modest profits, employees once again began raising their voices, asking for their fair share of whatever gains might be ahead—and the increasingly volatile up-and-down cycle of the industry seems destined to be repeated.

In each downturn, though, three important stakeholders suffer. Investors lose as company valuations drop and in some cases disappear. Employees, who have substantial firm-specific human capital, especially in an industry such as airlines in which compensation is often linked to firm-specific seniority, obviously suffer from layoffs and cuts to pay or other benefits. Customers suffer much-degraded service levels, as airlines cut back on amenities and delay needed investments in equipment and terminals, and as employees become more and more demoralized.

Yet the most recent upheaval reflects more than just another round of volatility. It also reflects a surge of new entrants that have spread price competition to an unprecedented degree. Around the world, the airline industry is becoming increasingly competitive as markets are deregulated and new entrants with low costs offer low fares. As a consequence, the industry is increasingly driven by cost-cutting pressures. This trend began in the United States after deregulation in the late 1970s; new-entrant low-cost competitors have played an increasing role since the 1990s and have continued to gain market share. They are growing even faster elsewhere in the world.

The annual number of miles flown by all passengers has grown by nearly 200 percent in the United States since deregulation, while the cost per mile has fallen by half, a growth rate and price performance that is not matched by any other relatively “mature” industry. In short, among the stakeholders in the airline industry, customers, especially customers in search of low prices, have been the winners. So if judged solely against the criterion of providing access for more consumers at low prices, airline deregulation would be judged a success. This is important. But while good for consumers’ budgets, does increasing price competition necessarily mean negative consequences for investors and employees—and for the service quality that customers experience? Do low fares inevitably mean low-quality jobs? Is volatility a fact of life based on the industry’s underlying characteristics? More ominously, will the degradation in human capital caused by lower and more volatile incomes, job security, and morale, along with the increased outsourcing of maintenance and other services, raise concerns about future safety? Are the risks of some type of meltdown in America’s air transportation system increasing? Or, can we fashion a more sustainable, less volatile industry that better balances the objectives of customers, investors, employees, and the wider society? And does deregulation necessarily mean the abrogation of government’s responsibility to oversee the industry, even as the industry shows clear signs of deterioration and an increasing risk of crisis?

These are reasonable, indeed vital, questions that are too seldom asked. Instead, too many business leaders assume that achieving low costs must mean low wages and no unions. As one veteran airline executive put it when discussing the state of the industry, “It’s all about price.” Too many union leaders assume that adversarial win-lose relations are the only model for labor-management relations. And too many policymakers accept as an article of faith that an unregulated market in which companies compete autonomously with strategies chosen by executives who are trying to maximize shareholder value is the best way to build an economy in a global marketplace—and the only way to compete. But at least one highly respected veteran airline industry executive, Robert Crandall, the former chief executive of American Airlines, believes the industry has suffered under the watch of government leaders who have been paralyzed by their blind faith in laissez-faire ideology:

There is no leadership at the federal level. We are in the grips of ideologues. We have had an administration that is convinced the market will solve the problem but the policies that make sense for the overall industry make no sense for the individual airlines and the policies that make sense for individual firms make no sense for the industry…. It is a classic case of needing sensible government regulation.3

The narrow views of business, labor, and government leaders tend to ignore history, overlook important alternatives and variations, and suffer from a myopic, U.S.-centric view of the world. They forget that American policymakers found it necessary to introduce regulations to stabilize the airline industry in its early years so that the industry could expand in an orderly way to meet the nation’s growing need for airline service. The same need for stability led policymakers to bring labor-management relations under the umbrella of a transportation labor law that provided for mediation and other procedures to settle disputes without resort to strikes or other service disruptions and to allow wages to be taken out of competition.

These views also overlook the considerable variation in strategies and practices in the U.S. airline industry. Hidden beneath the bleak results at the industry level are examples of individual airlines, both low-cost entrants and much older or so-called legacy airlines, that have pursued alternative employment practices and achieved more positive results for all of their stakeholders—low prices, high-quality service, profits, relatively good jobs, and less volatility. Two U.S. firms that will feature prominently in our analysis, Southwest Airlines and Continental Airlines, consistently are found in the upper half of the service-quality rankings reported in table 1.1 and have been listed among the 100 best places to work by Fortune magazine. The question then becomes whether and how these examples can be emulated to achieve a better balance among stakeholders and reduce volatility across the industry.

Some countries recognize they still have a national interest in balancing the interests of the multiple stakeholders needed to support a sustainable airline industry—one marked by fewer episodic crises and one that doesn’t lurch from one extreme to another—even as they move toward greater deregulation and negotiate “open skies” agreements. Around the world there are debates about different “varieties of capitalism,” with most Anglo-Saxon countries exemplifying a shareholder-maximizing model of a market economy, while the Scandinavian and Germanic countries and Japan exemplify a more coordinated-market approach to governing their economies and to balancing the interests of different stakeholders.4

Table 1.1. Service quality comparisons across U.S. Airlines

There is much to learn from these variations between companies as well as countries. But our research demonstrates that too many airlines, unions, and policymakers have been slow and reluctant learners. This book is an effort to open up the learning process. We do so by considering the trends as new entrants and legacy airlines around the world increasingly compete on costs. We discuss findings from case studies of airlines in the United States and other countries, analyzing the competitive strategies and the employment-relations strategies that airlines have adopted in response to economic pressures, and evaluate the outcomes for customers, employees, and other stakeholders. In particular, we will try to understand the lessons offered by airlines whose managers, unions, and employees have pursued and achieved more constructive relationships that reduce volatility, allow for quicker adaptation to changed conditions, and/or achieve low costs by providing good jobs that engage their workers. We conclude with recommendations for how the industry can better meet the needs of its multiple stakeholders.

Why Are These Questions Important?

One reason we should care about these issues goes to the heart of what citizens in an economy and society should expect from an industry. Most citizens are consumers and workers.5 As consumers we expect an industry to deliver good quality and safe products and services at affordable prices. And as workers we value good jobs that deliver on what some have called a social contract—hard work, loyalty, and good performance should be rewarded with dignity, good wages, and an opportunity to improve our economic security over time. Employment relationships should achieve a balance between efficiency and equity at work and should respect employees’ right to have a voice in shaping the terms and conditions under which they work.6 At a more macro level, the expectation is that wages and standards of living should improve approximately in tandem with growth in productivity and profitability. This is the essence of the social contract that governed employment relations in the United States for decades following World War II.7 Wages and living standards did indeed rise in tandem with increases in productivity over that period. Unions and companies found ways to both enhance efficiency and to divide the fruits of their efforts in a more or less acceptable manner. This tandem movement began to erode in the 1970s and the erosion accelerated after 1980. Between 1980 and 2005, productivity grew by more than 70 percent while real compensation levels for nonmanagerial workers remained flat. At the same time executive compensation increased greatly, growing from about twenty times the average worker’s wages in the 1950s to between two hundred and four hundred times average wages in 2007. Few defend such an increase on either equity or efficiency grounds.8 The old social contract has broken down in the airline industry and more generally across other sectors of the American economy. Although changes in technology, markets, and the workforce make it impossible and perhaps even undesirable to return to the past, can a new social contract be fashioned, one better tailored to the contemporary economy and workforce? As employment-relations specialists, we see this as a critical challenge and responsibility facing the airline industry, labor, and government leaders.

There is a second concern that we bring to this analysis. Most airlines are highly unionized in the United States and in many other countries. Research has demonstrated that many of the traditions and practices of collective bargaining and labor relations that were developed during the twentieth century should be changed to meet the different needs of workers, employers, and the political economy of the twenty-first century. Yet labor relations in the U.S airline industry, and in other countries as well, have been painfully slow to change. Some of the pain that has been endured by the workforce and the industry in recent years reflects the failures of earlier efforts to change on a more gradual and consistent basis. Thus, the parties need to learn from past failures (as well as successes) so that they can avoid repeating past mistakes. The evidence from the experiences of some parties shows there are better, more productive, and more satisfying ways to structure and govern employment relations in the airline industry. But it will take concerted and coordinated efforts from industry, labor, and government to lead the change process.

Beyond these employment-relations concerns, there is another dimension to “why this is important,” specific to the airline industry, namely, the externalities and centrality of airlines to most countries and their economies. Airlines are a key part of the transportation infrastructure in most countries. They are important to national and international security. They help generate and support at least four times the number of jobs beyond the direct workers of the airlines and are fundamental to the economic ...