1 | A Framework for Analyzing Collective Bargaining and Labor Relations |

DEFINING PRINCIPLES OF THE FIELD OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS

Whether we are at work or at leisure, we are affected by the conditions under which we work and the rewards we receive for working. Work plays such a central role in our lives and in society that the study of relations between employee and employer cannot be ignored.

This book traces how members of labor and management, acting either as individuals or as groups, have shaped and continue to shape the employment relationship. Employment is analyzed through the perspective of industrial relations, the interdisciplinary field of study that concentrates on individual workers, groups of workers and their unions and associations, and employers and their organizations and the environment in which these parties interact.

Industrial relations differs from other disciplines that study work because of its focus on labor and trade unions and the process of collective bargaining. Thus, this book describes how collective bargaining works and helps explain, for example, why it may lead to high wages in one situation and low wages in another.

The study of labor relations focuses on the key participants involved in the process, the role of industrial conflict, and the performance of collective bargaining. This chapter defines these various aspects of labor relations and describes how this book analyzes them.

THE PARTICIPANTS

The key participants (or parties) involved in the process of labor relations are management, labor, and government.1

Management

The term management refers to individuals or groups who are responsible for promoting the goals of employers and their organizations. Management encompasses at least three groups: (1) owners and shareholders of a company, (2) top executives and line managers, and (3) labor relations and human resource staff professionals who specialize in managing relations with employees and unions. Management plays key roles in negotiating and implementing a firm’s labor relations policies and practices.

Labor

The term labor includes employees and the unions that represent them. Employees are at the center of labor relations. They influence whether the firms that employ them achieve their objectives and shape the growth of unions and the demands unions make.

Government

The term government includes (1) local, state, and federal political processes; (2) the government agencies responsible for passing and enforcing public policies that affect labor relations; and (3) the government as a representative of the public interest. Government policy shapes how labor relations proceed by regulating, for example, how workers form unions and what rights unions have.

KEY ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT LABOR AND CONFLICT

Labor Is More than a Commodity

One of the most important assumptions that guides the study of labor relations is the view that labor is more than a commodity, more than a marketable resource. For instance, workers often acquire skills that are of special value to one firm and not to another. The possibilities that such workers will able to earn as much “in the labor market” as they can at their existing employer are limited. In addition, changing jobs often costs workers a lot: moving locations can be expensive and can also entail large personal and emotional costs. For these reasons and others, labor is not as freely exchanged in the open, competitive market as other, nonhuman market goods are.

Furthermore, labor is more than a set of human resources that a firm allocates to serve its goals. Employees are also members of families and communities. These broader responsibilities influence employees’ behaviors and intersect with their work roles.

A Multiple-Interest Perspective

Because employees bring their own aspirations to the workplace, labor relations must be concerned with how the policies that govern employment relations (and the work itself) affect both workers and their interests and the interests of the firm and the larger society. Thus, labor relations takes a multiple-interest perspective on the study of collective bargaining and labor relations.

The Inherent Nature of Conflict

A critical assumption that underlies analysis of industrial relations is that there is an inherent conflict of interest between employees and employers that derives from the clash of economic interests between workers seeking high pay and job security and employers pursuing profits. Thus, in the study of industrial relations, conflict is not viewed as pathological. Although conflict is a natural element of employment relations, society has a legitimate interest in limiting the intensity of conflicts over work.

Common and Conflicting Interests

Employers and their employees have a number of common interests. Both firms and their work forces can benefit, for example, from increases in productivity through higher wages and higher profits.

No single best objective satisfies all the parties in a workplace. The essence of an effective employment relationship is one in which the parties both successfully resolve issues that arise from their conflicting interests and successfully pursue joint gains.

Collective bargaining is only one of a number of mechanisms for resolving conflicts and pursuing common interests at the workplace. In fact, collective bargaining competes with these alternative employment systems. Not all employees, for example, perceive deep conflicts with their employers or want to join unions. In dealing with their employers, some workers prefer individual over collective actions. Others exercise the option of exit (quitting a job) when dissatisfied with employment conditions rather than choosing to voice their concerns, either individually or collectively.2

One of the roles of public policy is to give workers a fair opportunity to choose whether collective bargaining is the means they prefer for resolving conflicts and pursuing common interests with their employer.

Tradeoffs When Goals Conflict

Since many of the goals of the major actors—workers and their unions, employers, and the public or the government—conflict, it is not possible to specify a single overriding measure of the effectiveness of collective bargaining. Focusing on any single goal would destroy the effectiveness of collective bargaining as an instrument for accommodating the multiple interests of workers and employers in a democratic society.

Unions could not survive or effectively represent their members, for example, if employers were completely free to suppress or avoid unionization. Likewise, employers could not compete effectively in global or domestic markets if collective bargaining constantly produced wages or other conditions of employment that increased costs above what the market would bear.

THE THREE LEVELS OF LABOR RELATIONS ACTIVITY

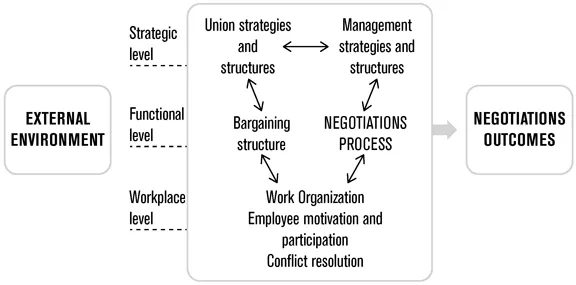

In this book, we use a three-tiered approach to analyzing the operation of labor relations.3 (Figure 1.1 provides the framework for this approach.) First we consider the economic, social, and legal contexts of collective bargaining, then we look at the operation and outcomes of the bargaining system.

Figure 1.1. The three-tiered approach to the study of labor relations

The top tier of industrial relations, the strategic level, includes the strategies and structures that exert long-run influences on collective bargaining. At this level, we might compare the implications for collective bargaining of a business strategy that emphasizes product quality and innovation with a business strategy that seeks to minimize labor costs.

The middle tier of labor relations activity, the functional level, or the collective bargaining level, involves the process and outcomes of contract negotiations. Discussions of strikes, bargaining power, and wages feature prominently here.

The bottom tier of labor relations activity, the workplace level, involves the activities through which workers, their supervisors, and their union representatives administer the labor contract and relate to one another on a daily basis. At the workplace level, adjustment to changing circumstances and new problems occurs regularly. A typical question at this level, for example, is how the introduction of employee participation programs has changed the day-to-day life of workers and supervisors.

It is through the joint effects of the environment beyond the company and the actions of the parties in this three-tiered structure that collective bargaining either meets the goals of the parties and the public or comes up short.

THE INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The perspective that guides our analysis of labor relations was first developed by institutional economists at the University of Wisconsin. John R. Commons (1862–1945), the person who most deserves the title father of U.S. industrial relations, defined the essence of institutional economics as “a shift from commodities, individuals, and exchanges to transactions and working rules of collective action.”4 Commons and his fellow institutionalists placed great value on negotiation and on compromise among the divergent interests of labor, management, and the public.

The institutionalists in the United States were heavily influenced in their thinking by the British economists and social reformers Sidney and Beatrice Webb, who were members of the Fabian socialist society. They viewed trade unions as a means of representing the interests of workers through the strategies of health and burial insurance, collective bargaining, and legislative action.5

In following the Webbs, the institutionalists rejected the arguments of Karl Marx. Marx argued that the pain of the exploitation and alienation that the capitalist system inflicted on workers would eventually lead to the revolutionary overthrow of the system. He believed that workers would eventually develop a class consciousness that would pave the way for revolution and the ultimate solution to their problems—a Marxian economic and social system. Marx supported trade unions in their struggles for higher wages, but he believed they should simultaneously pursue the overthrow of the capitalistic system.

There are some interesting similarities in the views of Commons, Marx, and the Webbs. Like Marx and the Webbs, Commons and other institutional economists rejected the view of labor as a commodity, for two fundamental reasons. First, the institutionalists saw work as being too central to the interests and welfare of individual workers, their families, and their communities to be treated simply as just another factor of production.6

Second, the institutionalists echoed the Webbs and the Marxist theorists by arguing that under conditions of “free competition,” most individual workers deal with the employer from a position of unequal bargaining power. That is, in the vast majority of employment situations, the workings of the market tilt the balance of power in favor of the employer. The selection from Beatrice Webb’s classic essay on the economics of factory legislation in Britain, shown in Box 1.1, amply illustrates this argument.

The institutionalists concluded that labor required protection from the workings of the competitive market and that unions could materially improve the conditions of the worker. This led them to advocate two basic labor policies: legislation to protect the rights of workers to join unions and legislation on such workplace issues as safety and health, child labor, minimum wages, unemployment and workers’ compensation, and social security.7 Thus, in addition to making scholarly contributions, the institutionalists served as early advocates of the legislative reforms that became the centerpiece of the New Deal labor policy during the administrations of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

BOX 1.1

Beatrice Webb on the Balance of Power between the Employee and Employer

If the capitalist refuses t...