Chapter One

Oil and Labor Exporters in the International Economy

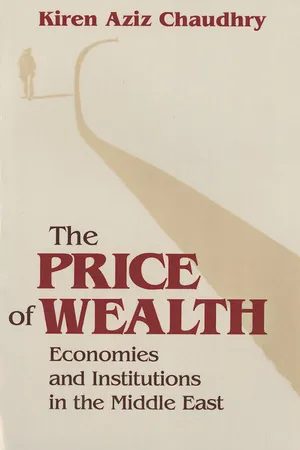

In 1973 the international price of oil quadrupled, precipitating the largest and most rapid transfer of wealth in the twentieth century. In the magnitude of the changes they wrought in the global economy, the oil shocks of the 1970s and early 1980s were comparable to the crises of the 1920s and 1930s. They created severe pressures for adjustment in the advanced industrial countries, triggering changes in economic policy and fundamentally altering macroeconomic relationships that had stabilized over the preceding three decades. In the developing world, sovereign and private borrowers gained access to recycled petrodollars, generating a host of economic dependencies that culminated in the debt crisis of the mid-1980s. The oil shocks transformed international financial markets, initiating a trend that assumed institutional form in the liberalization of major financial centers in the 1980s.

At the epicenter of these systemic changes—the Middle East—the deluge of oil revenues flooded a region whose countries had skewed but complementary national factor endowments. What decades of Pan-Arab sentiment had failed to achieve, the oil boom accomplished effortlessly: through the prosperous years of the 1970s and early 1980s, the economies of capital-scarce labor exporters and labor-scarce oil exporters became tightly linked through massive flows of labor and capital across national borders.

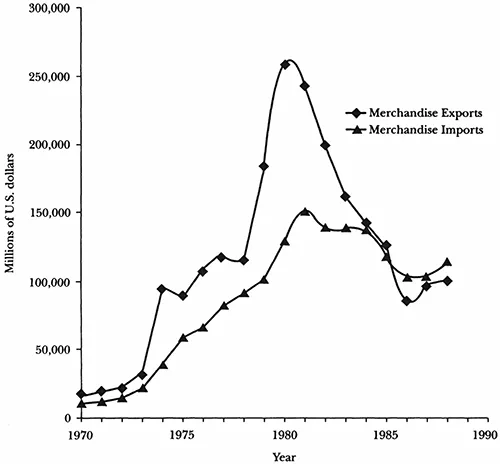

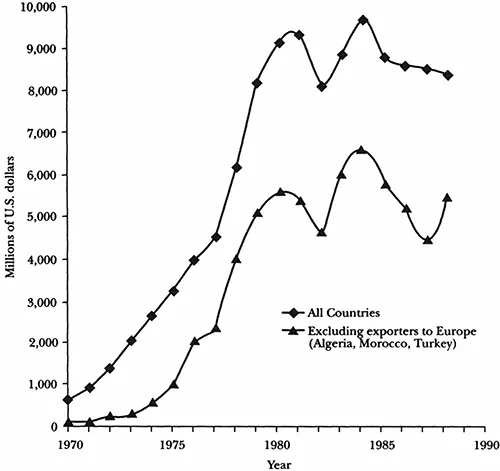

Shared resources made shared history. From Morocco to Iraq, the countries in the regional economy experienced three identical episodes of change: the oil boom (1973–1983), the recession leading up to the Gulf War (1984–1990), and the aftermath of the Gulf War. Between 1973 and 1983 the regional economy was characterized by unprecedented levels of interdependence between capital and labor exporters. In some instances—Tunisia and Libya, for example, or Yemen and Saudi Arabia—this interdependence was bilateral. Other labor-abundant countries, such as Jordan, Palestine, Syria, and Egypt, exported workers to many destinations. Oil revenues and labor remittances were supplemented by bilateral aid from the oil-rich Gulf states, Europe, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Aid constituted a substantial portion of government revenues for capital-scarce Middle Eastern countries; even for major labor exporters, aid at times outstripped remittance earnings. Oil revenues, aid, trade, remittances, and borrowing grew in tandem in the 1970s, reinforcing interdependence (as Figures 1.1–2 illustrate).

Quick to emerge, the regional economy was also short-lived. When oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, a severe regionwide recession ensued. From a 1980 high of $243 billion, oil revenues for major exporters fell to $67 billion in 1988. The economic downturn had an almost immediate impact on labor exporters, as government contracts in oil exporters were terminated and state spending dropped. Workers’ remittances declined, generating severe balance-of-payments crises. Similarly, Arab bilateral and multilateral aid declined from a high of $10.9 billion in 1981 to $2.5 billion in 1987. By 1989 there was a net outflow of $2.2 billion from labor exporters in repayment of Arab nonconcessional loans. Other debt payments simultaneously came due for many of the region’s heavy borrowers. The decline of region-specific capital flows and the rise of debt repayments in the mid-1980s coincided, roughly, with the termination of much of the bilateral aid that the Arab states had been receiving from the Soviet Union and the United States (see Figure 1.3).

The Gulf War formally severed links that had been weakening through the late 1980s and signaled the unqualified end of the regional economy. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, as well as the positions taken by different Arab governments during the conflict, reflected varying domestic economic crises. The rift between rich and poor took institutional form briefly in 1989, when the Arab Cooperative Council was created by Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, and Jordan as a counter to the oil-rich members of the Gulf Cooperative Council. By the end of the war these conflicts had become largely superfluous: in 1990, when the Gulf states placed themselves directly under the security umbrella of the United States, they dissolved the political and military foundations of the regional economy.

The boom decade did not change a single political regime in the Arab world: indeed, in the vast majority of cases, the same political leaders who ushered in the boom were still in charge in 1996. Yet the capital flows of the 1970s reshaped the domestic institutions and economies of each constituent country: whole classes rose, fell, or migrated; finance, property rights, law, and economy were changed beyond recognition.

The transmutations of the boom years rested on what an observer of sixteenth-century Spain once called “money made in air.” When the recession of 1986 hit, the foundations of the boomtime political economy crumbled, subjecting institutions and political relationships to new pressures. The recession thrust each country in the region back onto domestic endowments utterly transfigured over the preceding decade. In both labor and oil exporters, the project of constructing viable national economies began anew in an international economy radically different from that of the 1970s and early 1980s.

This book examines how the exogenous shocks of the 1970s and 1980s transformed the domestic political economies of two countries embedded in this regional system. Yemen and Saudi Arabia are extreme cases of dependence on, respectively, labor remittances and oil, the two dominant forms of capital inflows in the Middle East. Tracing these cases from their relative insularity in the interwar period, through the dramatic economic changes of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, I explore the changing links between international and domestic political economies in late developers. In doing so, I expose the process by which exogenous shocks transform domestic interests and institutions at one juncture only to undercut the foundations of these accommodations at another. Clearly defined economic cycles (connected to oil prices) reveal contours of change and conflict that remain hidden in more stable environments. The “boom” pattern (1973–1983) exposes responses to soaring external capital inflows, whereas the “bust” pattern (1986–1996) demonstrates how institutional and political relationships forged in the boom break down in times of crisis, conditioning institutions, organizations, and policy outcomes in unexpected ways. In these clearly defined sequences we can test the relative weight of international, institutional, and interest-based explanations of change in the domestic political economy.

Yemen and Saudi Arabia had similar beginnings: neither country had a colonial legacy, and the oil boom of the 1970s coincided in both with the construction of a central bureaucracy and the creation of a national market. Two different types of capital flows thereafter shaped state structure and capacity, national integration, and business-government relations in divergent ways, revealing the discontinuous, highly contingent nature of institutional change in late developers.

Before unification of the national market in Saudi Arabia and in Yemen, one would have been hard put to identify what “the international economy” meant for local communities in the Arabian Peninsula. Arabia existed in a Braudelian world of international trade routes, migration, and currency flows in which major international events—World War I, the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the collapse of the gold standard—had significant local effects. The communities that experienced these effects, however, had yet to be defined at the national level, and mechanisms for coping with economic change were local. The very institutions that separate the national from the international, a national market and a state, did not exist. Nevertheless, in this period of relative isolation and poverty, substantial institutional change occurred: in quite dissimilar ways, between 1916 and 1973, a central bureaucracy and army were forged, the currency was unified, and a national market was created in both Yemen and in Saudi Arabia.

The boom rapidly transformed each of these fundamental institutions. In the 1970s, almost unnoticed, the tax and regulatory bureaucracy was dismantled, the financial system was completely restructured, and new institutions arose in response to the influx of oil revenues and labor remittances. These new institutions, born of a sudden connection to the international economy, in turn reshaped society. Through the institutionally mediated flow of remittances and oil revenues, economic and ascriptive categories, on the wane in the 1960s, realigned. Then, in the bust, political relationships forged in the boom years broke down, generating intense conflicts over the future shape of domestic institutions. Scarcity bred a new politics centered explicitly on who would design the institutions that governed the national market. Conflict reentered the two systems, engaging groups constituted during the boom.

In the 1980s, policy goals were identical, but outcomes diverged. Starting in 1983, plummeting oil prices precipitated a severe economic recession in Saudi Arabia, which rapidly affected the Yemen Arab Republic, Saudi Arabia’s southern neighbor and the main source of its imported labor force. The dimensions of the crisis are legendary. Saudi Arabia’s oil revenues declined from a high of $120 billion in 1981 to $17 billion in 1985. Yemeni labor remittances dropped by about 60 percent, and development aid, which had covered the entire current budget of the Yemeni government, dropped to only 1 percent of the state budget Both countries experienced severe fiscal crises that prompted wide-ranging economic reforms in 1986–87 designed to cut government outlays of foreign exchange, increase domestic taxation, and regulate what had been two of the most open economies in the world. Reform efforts produced different outcomes in the two countries. The Yemeni government’s thoroughgoing package included heavy, retroactive taxation, foreign trade reforms, and a host of economic regulations that restricted the activities of its powerful private sector. In contrast, private elites in Saudi Arabia forced the Saudi government to withdraw most reforms within days of their enactment.

If economic power produces political power—if autonomous states are “strong,” and independent groups are efficacious—this outcome is exceedingly puzzling. Oil revenues had accrued directly to the Saudi government over the boom decade—making government spending virtually the sole engine of domestic economic growth and freeing the state from reliance on domestic sources of revenue—whereas privately controlled labor remittances had bypassed the Yemeni state altogether. Entering the country through informal banking channels, remittances had expanded an already powerful domestic commercial and industrial elite. Paradoxically, in neither Yemen nor Saudi Arabia did the wealth of the boom translate into efficacy in the bust: the financially autonomous and affluent Saudi state could craft but not implement austerity measures; the Yemeni private sector could not resist the draconian reforms of a government that was poor, administratively weak, and politically isolated.

The economic reforms of the 1980s open a window on the way that oil revenues and labor remittances had transformed the political economy of Saudi Arabia and Yemen, revealing the radically different nature of their interactions with an international economy that was itself experiencing fundamental change. Going back through the 1970s, to Yemen and Saudi Arabia as they were before the oil boom, this book traces the genealogy of three fundamental institutions—the national market, the central bureaucracy, and business-government relations—to explain the processes through which institutional change occurs.

I develop three main arguments. First, the analytical tasks of explaining institutional origins and institutional change in periods of isolation and of immersion in the international economy are not identical. Moreover, specifying the mechanisms of institutional change in periods of relative isolation from exogenous forces is critical, not only to appreciate the impact of the international economy but also to delineate the explanatory scope of theory. The unification of the national market under the aegis of the modem state was a historically specific process. That process actually created the geographical and political boundaries of community which form the unit of analysis commonly used in studying the effects of international change on national institutions. The creation of a system of states and national markets demarcated the boundaries between the international and national arenas: they created the categories that subsequently defined the nexus of institutional change. By focusing on the same institutions through several conjunctures of international and local time, one can appreciate the empirical limits on theorizing institutional change.

Second, the mechanisms through which international forces shape domestic institutions vary, depending both on forms of integration into the international economy and on broad sea changes in the organization of the international economy itself. Neither the international economy nor any society’s experien...