1The Importance of Mondragón

Mondragón is still far from a household word in the United States or elsewhere, but for growing numbers of researchers and activists, this cooperative complex based in a small Basque city of Spain is a fascinating example of success in a form of organization for which failure is the general rule. The story of Mondragón is the most impressive refutation of the widely held belief that worker cooperatives have little capacity for economic growth and long-term survival.

A negative judgment on worker cooperatives was first rendered early in this century by the prestigious social scientists Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Their verdict has been the conventional wisdom ever since:

All such associations of producers that start as alternatives to the capitalist system either fail or cease to be democracies of producers….

In the relatively few instances in which such enterprises have not succumbed as business concerns, they have ceased to be democracies of producers, managing their own work, and have become, in effect, associations of capitalists…making profit for themselves by the employment at wages of workers outside their association. (Coates and Topham 1968, 67)

It is now clear that the Mondragón cooperatives have met both tests posed by the Webbs. Besides their employment growth—from 23 workers in one cooperative in 1956 to 19,500 in more than one hundred worker cooperatives and supporting organizations—their record of survival has been phenomenal—of the 103 worker cooperatives that were created from 1956 to 1986, only 3 have been shut down. Compared to the frequently noted finding that only 20 percent of all firms founded in the United States survive for five years, Mondragón’s survival rate of more than 97 percent across three decades commands attention.

Nor have the Mondragón cooperatives lost their democratic character. They continue to operate on the one-member one-vote principle. Many of the cooperatives employ no nonmembers, and, by their own constitutions and bylaws, no cooperative may employ more than io percent nonmembers.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF A UNIQUE CASE

Responding to the first report on Mondragón at the 1976 annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (Gutierrez-Johnson and Whyte 1977), a discussant dismissed the case as simply a human-interest story. His argument was that the success of Mondragón depended on two conditions: the unique nature of the Basque culture and the genius of the founder, Father José María Arizmendiarrieta. Because neither of these conditions could be reproduced anywhere else in the world, he felt the Mondragón story was without scientific or practical significance.

The most general answer to such a critic is that the criticism is itself unscientific. It is one of the fundamental principles of science that, on discovering an exception to a law or generalization, one does not rationalize it away and reaffirm the general principle. On the contrary, one concentrates one’s attention on the exception, in the hope that it will lead to a modification of the previously accepted generalization, or to a more basic reformulation, opening up new avenues of scientific progress. Nevertheless, we are now grateful to this critic for forcing us to think harder, both about Mondragbn in the context of the Basque culture and about the general scientific and practical implications that can be drawn from this case.

QUESTIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

The salience of the questions we raise throughout this book depends in part on the time period we are addressing. Mondragón experienced rapid growth from 1960 through 1979. Employment leveled off from 1980 through 1986, while Spain was mired in a severe recession. There were slight drops in employment in 1981 and in 1983, and then small increases again from 1984 through 1986.

Although questions regarding economic success and failure are relevant for both periods, the primary question for the years through 1979 is, How did Mondragón manage such rapid and sustained growth? For the later period, the question is, How has Mondragón been able to survive—and even resume modest growth—in the face of extreme economic adversity?

While seeking to answer these questions, we will probe the Mondragón experience for what it can teach us about the problems and possibilities of creating worker-owned firms and of maintaining worker ownership and control through periods of growth. We will learn about efforts to achieve economies of scale while maintaining local autonomy and grass-roots democracy. We will examine unique systems for stimulating and guiding entrepreneurship, for providing cooperatives with technical assistance, and for intervening to assure the survival of a failing cooperative. We will also analyze the process of technological and organizational change as it was carried out within Mondragón’s individual firms, with the stimulus and guidance of an industrial research cooperative.

We make no claim that Mondragón has all the answers to the problems of worker cooperatives. In fact, its members and leaders tend to be more critical of their organizations than admiring outsiders are. Nevertheless, Mondragón has had a rich experience over many years in manufacturing products as varied as furniture, kitchen equipment, machine tools, and electronic components and in printing, shipbuilding, and metal smelting. Mondragón has created hybrid cooperatives composed of both consumers and workers and of farmers and workers. The complex has developed its own social security cooperative and a cooperative bank that is growing more rapidly than any other bank in the Basque provinces. The complex arose out of an educational program begun in 1943 for high school—age youth. It now includes college education in engineering and business administration. These various cooperatives are linked together in ways we will explore.

Although any cooperative program must be developed in the context of the culture and political and economic conditions in the region and nation of its origin, Mondragón has such a long and varied experience that it provides a rich body of ideas for potential adaptation and implementation elsewhere. Such ideas apply most clearly to worker cooperatives and other employee-owned firms, but Mondragón also provides fruitful lessons in regional development and in how to stimulate and support entrepreneurship, whatever the form of ownership. An expanding minieconomy, the cooperative complex is far from self-contained, yet the network of mutually supporting relationships on which it is based provides an important key to regional development.

We also see possibilities for private companies to learn from Mondragón as they seek to foster labor-management cooperation. In fact, the learning can go in both directions if we think more generally of the conditions necessary for participation and cooperation in any organization devoted to the management of work.

THE GROWING INTEREST IN WORKER OWNERSHIP

Interest in Mondragón has grown in response to the explosive growth of worker cooperatives and employee-owned firms in recent years, especially in Europe and the United States. Of the 11,203 worker cooperatives in Italy in 1981, half had been established since 1971. Of the 1,269 in France in 1983, 66 percent had been created since 1978. And of the 911 in England in 1984, 75 percent had been founded since 1979 (Centre for the Study of Cooperatives 1987).

The most impressive worker cooperatives in the United States have been the plywood firms in the Northwest (Bellas 1975), but the most spectacular growth of worker ownership in recent years has been in the form of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPS). In 1970, employee ownership was exceedingly rare in the United States. By 1986, Corey Rosen, executive director of the National Center for Employee Ownership, estimated that about 7,000 firms employing 9 million employees had some form of shared ownership. Just three years later, the number had grown to 10,237 firms employing 11,330,000 employees (Rosen and Young 1991, 20).

Employee ownership, in various forms, has been attracting growing interest internationally, especially in the Soviet Union and other parts of Eastern Europe. The sudden collapse of the command economies has been heralded as symbolizing the triumph of capitalism over communism and has made privatization a popular goal of economic reform programs. But how is this goal to be attained? Answering this question involves answering two related questions: how can private ownership be stimulated in new enterprises, and how can large state-owned firms be converted to private ownership?

In this new scene, employee or worker ownership has been transformed from a fringe issue to a central concern. In nations where there are no established private capitalists and no existing national private firms capable of providing the capital to take over state companies, trying to sell state companies to foreign firms may be impractical or politically undesirable. Increasingly, economic planners are thus looking for ways of selling firms to their employees.

Each nation must find its own ways of facilitating these transactions, but, not surprisingly, economic planners have been reaching out for information and ideas from abroad. An American social invention, the employee stock ownership plan, is currently being examined to see how it can be adapted to the culture, history, and patterns of economic and political organization in various European nations. The striking success of the Mondragón worker cooperative complex has revived interest in worker cooperatives as an alternative to state ownership or individual private ownership.

We make no claim that Mondragón provides the best way to advance privatization in any country. Rather, we believe that Mondragón has created social inventions and developed social structures and social processes that have enabled it to overcome some of the major obstacles to the adaptation of worker cooperatives in the past. In our final chapter, we examine some of the lessons to be learned from the Mondragón experience. To put those lessons in their necessary context, we begin by describing the creation and evolution of the Mondragón cooperatives. We also discuss how they have changed through decades of experience and how they have struggled to maintain a balance between their social commitments and economic realities.

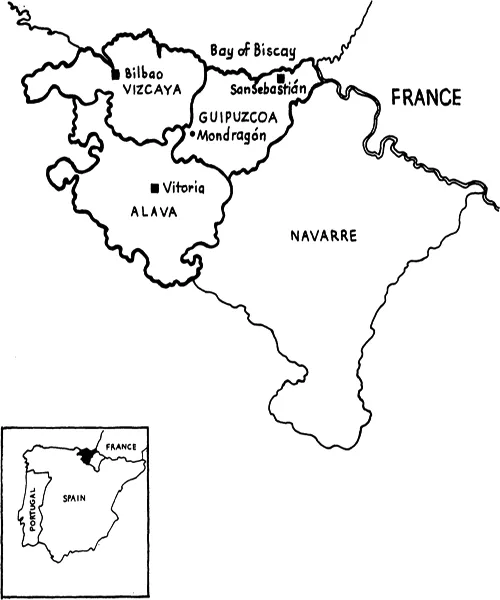

THE BASQUE COUNTRY. The three provinces of Guipuzcoa, Vizcaya, and Alava make up the autonomous Basque government, with its capital at Vitoria. The province of Navarre and the adjoining area of France also have large Basque populations.

2The Basques

To outsiders, the first contact with the Basque country may be puzzling, for although all but a few old-timers speak Spanish like the natives they are, and economically and politically the Basques are part of Spain, they are culturally distinct from other Spaniards. Without romanticizing or exaggerating this distinctiveness, it is important for one’s understanding of Mondragón to view Basque culture in the context of regional and national economic and political development.

SETTING THE BACKGROUND

The most distinctive aspect of Basque culture is the language, Euskera, which is unrelated to any other. Although Euskera is spoken by only 25 percent of the Basques, more than 56 percent of the people of Guipuzcoa, the province where Mondragón is located, are competent in the language (Tarrow 1985, 248). In recent decades, competence in Euskera has been emphasized in Basque schools, especially private schools founded to preserve and strengthen Basque culture.

Basques are found along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean (the Bay of Biscay) and on both sides of the Pyrenees, but predominantly in Spain. The Basque country in Spain consists of either three or four provinces depending on whether one accepts the legal definition or that espoused by some Basque nationalists. Following the reinstitution of democracy after the death of Franco, the provinces of Alava, Guipuzcoa, and Vizcaya joined to form the semi-autonomous regional government. Many citizens of northern Navarre consider themselves Basques, but, because of their ancient attachment to the Kingdom of Navarre and greater acceptance of Spanish culture, Navarre remains outside the Basque regional government. Including the four provinces, the Basque population in Spain is estimated at 2.7 million. Geographically, the cooperatives in the complex are most heavily concentrated in Guipuzcoa, followed closely by Vizcaya, which, like Guipuzcoa, is directly on the coast. The complex includes small but growing numbers of cooperatives in Navarre and Alava.

The Basque region in Spain is generally mountainous and moist. Historically, the Basques have supported themselves precariously by sheep herding and by farming the generally unfavorable terrain, but early in their history they moved into seafaring, shipbuilding, and iron mining and steel fabrication.

As early as the fourteenth century, Basque coastal cities were the main Spanish centers of shipbuilding, and they remained important through the eighteenth century. As shipbuilding declined, iron and steel continued to develop. Steel for the famous Toledo swords came from a mine and workshop near Mondragón. As we learn from the distinguished expert in Basque studies, Julio Caro Baroja, “By the middle of the 17th century the village of Mondragón is known not only for its swords but also for the ‘arms of all types’ that were coming from its workshops’* (1974, 170).

These industrial pursuits had a major impact on the countryside. As Caro Baroja said (1974, 172), “Shipyards and foundries are schools of artisanship, their influence spreads throughout the country.”

The region developed autonomously until the political consolidation of the nation during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella in the fifteenth century. The history of the region since then must be seen against a background of struggle by local leaders to preserve their autonomy and the efforts of the Crown first to accommodate that autonomy and then to suppress it.

The Basques took advantage of the political struggles of the kings of Navarre and Castile against the feudal lords in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Up to this time, allied with the King of Aragon, the lords had controlled the countryside, and fighting among them had retarded the growth of commerce.

In their struggle against the King of Aragon and the feudal lords, the kings of Navarre, and later Castile, encouraged the growth of urban centers. To migrants to the towns and cities, the Castilian Crown offered freedom from the serfdom owed to feudal lords. The monarchs saw freeing the townspeople from the control of the feudal lords as a means of extending central control, whereas the Basques saw it as enhancing opportunities for local autonomy.

This struggle for autonomy was supported by the development of a distinctive Basque myth. By the fifteenth century, the Basques had persuaded the Spanish king to declare all inhabitants of Guipuzcoa hijosdalgos (people of known parentage or, literally, “sons of something”) and thus “noble” and “equal” in relation to each other. (Hidalgo, a shortened form of the word, was a title given in Spain to members of the minor nobility.) Ironically, the myth did not base egalitarian claims on the virtues of the common man but rather...