1 INTRODUCING RAPTORS

Birds evolved into the main groups or orders we know today at an early period in their history.

The order Falconiformes, the subject of this book, is typical in this respect.

Leslie Brown and Dean Amadon, 1968

IF ONLY IT WERE AS SIMPLE to classify birds of prey now as it was in 1968. Although raptors are relatively easy to characterize, defining them biologically is another matter entirely. Let’s start with their characteristics.

Raptors are relatively large and long-lived diurnal (active during daylight hours) birds of prey with keen eyesight. Highly successful, raptors first appeared in the fossil record some 50 million years ago. Today, they include approximately 330 species of hawks, eagles, falcons, vultures, and their allies globally. Found on every continent except Antarctica, as well as on many oceanic islands, raptors are one of the most cosmopolitan of all groups of birds. Many species migrate long distances seasonally, sometimes between continents. Others, including many that breed in the tropics, do not migrate at all, at least not as adults.

Like all birds, raptors have feathers and lay eggs. Unlike most other birds, however, raptors exhibit reversed size dimorphism, a phenomenon in which females are larger than their male counterparts. What follows is my attempt to detail the biology of these birds, to point out how they are both similar in many ways to other species of birds and, at the same time, distinctive. Although I sometimes mention owls, the nocturnal ecological equivalent of raptors, I do so mainly to point out similarities and differences between them and diurnal birds of prey. In this chapter, I define what makes a raptor a raptor, describe the different types of raptors and how they are related to one another, and describe their history in the fossil record. I also describe the common and scientific names of raptors. In sum, this chapter introduces the “players.” The remaining chapters discuss their biology and ecology and their conservation status. (Technical terms are defined in the Glossary. Scientific names, or binomials, of all organisms mentioned in the book are listed in the Appendix.)

To reiterate, characterizing diurnal birds of prey—which is what I have done so far—is far easier than actually defining them. Unlike water, whose definition, if you’ll pardon the pun, can be distilled into its chemical elements as simply H2O, trying to define raptors is a bit more difficult.

Although there is a tendency to define the birds we group as raptors on the basis of their predatory habits, diurnal birds of prey are not defined by predation alone. Indeed, vultures, which most biologists (including me) call raptors, are largely nonpredatory, obligate scavenging birds. Furthermore, any bird that feeds on living animals is, by definition, predatory. But insect-eating warblers, worm-eating robins, and fish-eating herons are not considered raptors. So if predation does not distinguish raptors from other birds, what does?

Anatomy certainly plays a role. Unlike other “predatory” birds, raptors possess large, sometimes hooked beaks, and powerful, needle-sharp claws called talons. Most diurnal birds of prey use their talons to grasp, subdue, kill, and transport their prey. The English word “raptor” itself comes from the Latin combining form “rapt” meaning to seize or plunder. (That said, some raptors, including many falcons, use their beaks to kill their prey. But more on that later.) The oversized beaks and talons of raptors allow them to seize, rapidly kill, and consume many types of prey, including some that are relatively large compared with the raptor’s own body mass and, as such, are potentially dangerous. Peregrine Falcons, for example, which are known to feed on more than 500 different species of birds globally, sometimes catch and kill waterfowl that are twice the mass that they are.

But in the end, ecology and anatomy alone do not define raptors. After all, several raptors, including most vultures, are not predatory at all, and a few eat fruit. Others have chicken-like beaks and modest talons. A third distinguishing characteristic, at least in part, is their evolutionary history. The ancestral relationship, or what biologists call their phylogeny, of diurnal birds of prey also helps define raptors. But unfortunately it, too, is not as simple as it appears. In fact, the quote at the head of this chapter is technically out-of-date.

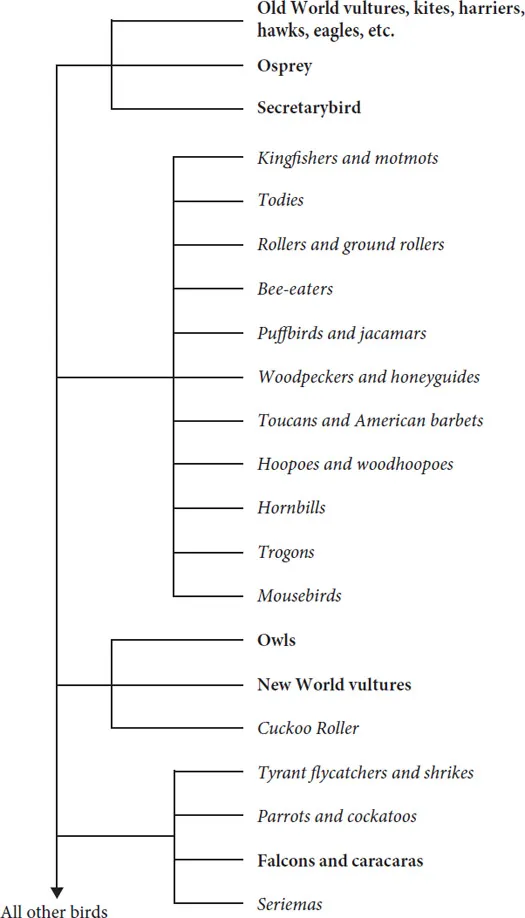

All currently recognized groups of diurnal birds of prey trace their origins to several ancient avian lineages that evolved tens of millions of years ago. Some of the most recently published evidence, which are molecular phylogenies based on similarities in DNA sequencing to determine the lineages (i.e., birds that share more similar DNA are believed to be more closely related), indicate that hawks, eagles, kites, harriers, and Old World vultures (vultures that occur in Europe, Asia, and Africa) cluster tightly in the phylogenetic family Accipitridae and, thereafter, cluster together with the Secretarybird, the sole member of the family Sagittaridae, and the Osprey, the sole member of the family Pandionidae. These are what some might call “core raptors,” in that they share a single common ancestor. These groups of species, however, are separated from other groups that most consider raptors by more than a dozen families of terrestrial and arboreal birds that include bee-eaters, trogons, and woodpeckers.

Family relationships involving diurnal birds of prey and owls based on a recent molecular analysis. Note the close relationships of most diurnal raptors and the more distant relationships of owls, New World vultures, and, particularly, falcons and caracaras. (After Ericson et al. 2006.)

New World vultures (condors and vultures that are found only in the Western Hemisphere), in the family Cathartidae, which are phylogenetically distinct from Old World vultures, are next most closely related to the core raptors. After them come the falcons and caracaras, in the family Falconidae. Add to this the fact that nocturnal birds of prey, or owls, appear to be the closet living relatives of New World vultures, and that parrots appear to be the closest living relatives of falcons and caracaras, and you have a rather complicated and confusing ancestral lineage in which the birds we now call raptors are not monophyletic (belonging to a group derived from a single common ancestor), but rather are polyphyletic (belonging to a group with multiple origins whose biological similarities result from convergent evolution, not common ancestry).

Although the final verdict is not yet in, it is fair to say that the ancestral lineages of raptors are several and that whereas the group I call core raptors are each other’s closet relatives, New World vultures and, to an even greater extent, falcons and caracaras, are not. All, however, are grouped as raptors because of their similar biological characteristics, not because of their evolutionary histories. So there you have it, about as complicated a definition as one can imagine. But even now, we are not yet out of the woods.

TYPES OF RAPTORS

Like other biologists, ornithologists define species as groups of interbreeding birds that are reproductively isolated from other groups of birds. Overall, members of the same species share suites of traits that other species lack. Such traits, which can include overall body size and shape and other anatomical features, as well as song, habitat use, diet, and behavioral traits, are said to be defining characteristics of a species. Traditionally, avian biologists used such features to classify raptors into species, as well as to determine the ancestral relationships among them. More recently, the DNA genetic analyses mentioned above have been used to determine which species fall into the different categories of raptors.

Old and New World Vultures

Ornithologists currently recognize twenty-two species of largely carrion- eating birds of prey as vultures, including seven species of New World vultures and condors and fifteen species of Old World vultures. (Africa’s Palm-nut Vultures, despite their name, are not included here, as their ancestry remains unclear.) The most recently recognized species of vultures is southern Asia’s Slender-billed Vulture, which was recognized as a distinct species around 2005 based on both molecular and anatomical evidence and separated from the Indian Vulture with whom it was formerly lumped. Africa, with eleven species of Old World vultures, is the center of vulture diversity in the Old World. South America, with six species of New World vultures, is the center of vulture diversity in the New World. There are no vultures in Australia or Antarctica and, with the exception of Egyptian Vultures and Turkey Vultures, vultures typically do not occur on oceanic islands.

The phylogeny of New World vultures, a distinct group of seven Western Hemisphere birds of prey that is distributed throughout most of the Americas, and that includes North America’s California Condor and South America’s Andean Condor, has long attracted the attention of avian taxonomists. Although they closely resemble Old World vultures in their feet, beaks, and largely featherless heads, New World vultures differ substantially from other diurnal birds of prey, including Old World vultures, in many anatomical and behavioral ways, which over the years have led many ornithologists to question their ancestral relationships.

In the early 1800s, taxonomists placed the New World vultures in a separate family from all other raptors, and in 1873, the influential English vertebrate zoologist A. H. Garrod removed the New World vultures from other raptors entirely, placing them next to storks in the family Ciconiidae, mainly because of similarities in the arrangements of their thigh muscles. The taxonomic confusion continued well into the twentieth century. In 1948, Washington State University’s George Hudson claimed that New World vultures “have no more natural affinity with hawks and falcons than do owls” (something that more recent DNA analyses have confirmed). In the 1960s, two different biologists using similarities in egg-white proteins to determine bird relationships reached opposite conclusions regarding the New World vultures and other raptors. One concluded the two groups were closely related, the other that they were not.

In 1967, the University of Michigan’s J. David Ligon published a paper that linked New World vultures to storks rather than to other raptors on the basis of “striking anatomical similarities” including perforated nostrils, nestling plumages, and the lack of syringeal, or “song-box,” muscles. In 1983, the California museum worker Amadeo Rea reached essentially the same conclusion, pointing out several behavioral similarities between the two groups, including disgorging the contents of their stomachs when frightened, and urohidrosis, the habit of urinating on one’s legs, presumably for thermoregulation.

In 1990, a then seminal molecular analysis by Charles Sibley and John Ahlquist at Yale University appeared to close the book on the subject when it concluded that the then popular DNA-DNA hybridization technique also linked New World vultures to storks. Shortly thereafter, the American Ornithologists’ Union, the final arbitrator in North American ornithological taxonomy, removed New World vultures from the avian order Falconiformes and placed them next to storks in the wading-bird order Ciconiiformes. (Note that avian orders such as Falconiformes are used by taxonomists to group similar families of birds.)

The taxonomic tide, however, began to shift in 1994, when the American Museum of Natural History researcher Carole Griffiths published a detailed examination of the syringeal anatomy of raptors and several other groups of birds including both owls and storks. After examining more than 180 song boxes, Griffiths concluded that New World vultures were not at all closely related to storks and indeed belonged in the order Falconiformes. More recent DNA analyses, including that mentioned above, support her assessment and in 2007, the American Ornithologists’ Union reversed itself and removed New World vultures from the order Ciconiiformes and placed them back in the order Falconiformes, making them, once again, raptors. Although the meandering history of the official taxonomic relationships of New World vultures offers something of an extreme case of shifting evidence and ideas, the more recent placement of falcons and their allies next to parrots confirms that a lot more remains to be learned regarding the ancestral relationship of the birds we call raptors.

Hawks, Eagles, and Their Allies

Estimates of the number of species of hawks, eagles, kites, and harriers alive today range from about 235 to about 240. There are approximately 35 species of kites and kite-like birds, 13 harriers, 60 eagles, and 120 or so hawks and hawk- and eagle-like birds. Representatives of these groups exist on many oceanic islands and on all continents except Antarctica. Several species within these groups are particul...