![]()

Part I

MILIEU

![]()

1

FAITH IN DEVELOPMENT

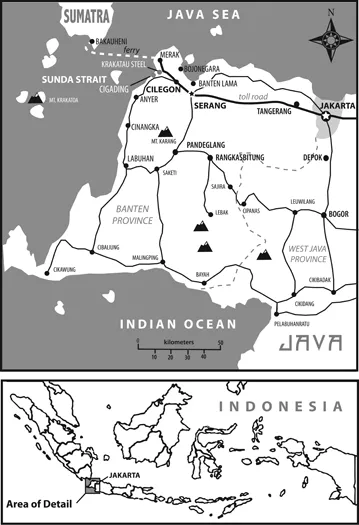

From Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital city, the most common trip to Krakatau Steel takes place on one of the country’s few four-lane toll roads. During the roughly one-hundred-kilometer journey to the western extremity of the island of Java the landscape goes through several alterations. After one passes through the first set of toll gates the city itself changes from densely packed storefronts sporting signs and banners that appear more grandiose than their interiors, to a more open spatial distribution where once rural villages butt up against recent housing developments catering to the capital region’s middle and upper classes. Several massive shopping malls sprout up on the landscape like giant fungi after a warm monsoon rain and eventually the landscape gives way to flat rice paddies (sawah) bordered by banana trees and simple wooden shelters. When one enters the province of Banten, which lies alongside the eastern border of Jakarta, these tranquil fields are dissonantly interspersed with more recently built factories that seek to take advantage of proximity to the city’s infrastructure, capital, and consumers.

Driving the road can be a knuckle-whitening experience as huge buses ply this route at breakneck speeds, their doors ripped off and their engines belching great volumes of noxious black exhaust. Roaring imperiously down the tollway and swerving recklessly from lane to lane, they obey the only real rule that seems to govern Indonesian roads: the largest vehicle always possesses the right of way. These buses are headed to towns in Banten; many routes end in Merak, at the western tip of Java, where passengers can catch ferries that will take them to the southernmost extremity of the neighboring island of Sumatra. Brightly painted cargo trucks with elaborately airbrushed images of fierce forest fauna and scantily clad women also compete for space on the highway, albeit at somewhat lower speeds and with considerably less maneuver. In this direction, they mostly carry industrial goods back to Sumatra having deposited shipments of that island’s agricultural commodities, such as coconuts, durians, and cows, in the Jakarta region.

The stretch of road between Jakarta and Merak seems to be perpetually under construction as workers, who sleep in makeshift camps just off the shoulder, pound at concrete and asphalt with pitifully small metal hammers and carry away barefoot the debris in handwoven baskets. Indonesia’s nouveau riche also travel the highway in spruced up Toyota Kijang SUVs and sometimes more opulent German sedans, commuting from Jakarta to managerial jobs in Banten’s scattered factories or on weekends making a trip to the beach at Anyer, which seems to be of interest based more on its past reputation rather than its contemporary appearance. Depending on the season and air quality, Gunung Karang, a dramatic, forest-flanked tropical volcano will come into view about midway through the journey. The size and position of the mountain on the horizon indicates roughly how close one is to Serang (Banten’s recently designated provincial capital), Banten Lama (the seat of the prominent sultanate of Banten during its period of peak influence in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), and Cilegon (the city that services Krakatau Steel and the cluster of industries that it has attracted).

After a trip of roughly two hours from Jakarta, traffic delays notwithstanding, one arrives in Cilegon, or Steel City (Kota Baja), as it is sometimes called by Indonesians. Leaving the toll road at the east Cilegon exit and driving toward the factory zone takes one through the municipality itself, which bears the hallmarks of a frenzied town that perhaps grew too rapidly and definitely without much foresight or organization. The main road through town was originally part of the infamous Daendels Road that the Dutch colonial administration, using corvée labor, had constructed from one end of Java to the other in the early nineteenth century. A four-lane strip of asphalt, the road is crowded with horse-drawn carts, massive trucks, and all manner of transportation in between. It is the main artery for this city of roughly three hundred thousand inhabitants and serves a dense sequence of storefronts and businesses. A wide range of consumer goods—electric rice cookers, television sets, and Chinese motorbikes—is visible from the roadway, baking in the blazing sun that seems ubiquitous in Cilegon even in the rainy season. Three boxy shopping malls, decidedly less opulent than their enormous cousins in Jakarta, are evenly spaced through the city along the main artery: Ramayana at the east end, Matahari close to the city’s central square, and the chaotic, stifling SuperMal Cilegon, which lies at the city’s west end about seventy-five meters down the road from the Al-Hadid mosque. The mosque was built by Krakatau Steel in the 1970s as compensation for a mosque that was previously located on land that the company “absorbed” during a period of rapid expansion. It once must have been one of the most impressive buildings in Cilegon, but after three decades it bears the tired visage of a dilapidated modernism that characterized a number of company-constructed structures.

Figure 1.1. Map of Banten. This new province was created in 2000. Credit: Jos Sances, Alliance Graphics.

While I was conducting research in Cilegon and its environs, the main road was incessantly clogged with minivans (angkot) that plied several routes through town. Usually there were more of these buses than there were passengers, which caused their drivers to drive extremely slowly while looking for passengers and then become exceptionally aggressive when a prospective rider appeared, lurching spasmodically to the curb. This unpredictable traffic led to bottlenecks and backups; a source of constant consternation among some employees of Krakatau Steel and other automobile-owning inhabitants of the region, who usually explained the erratic nature of the drivers by asserting, as if it was a self-evident fact, that they “lacked education” (kurang ajar). Most employees of the company were from other parts of Indonesia, while those who drove the buses were the offspring of people with families who had lived in Banten for several generations, if not longer. These two groups, locals (putra daerah) and newcomers (pendatang), coexisted in an uneasy détente and seldom mixed outside the market, evoking what James Furnivall had some decades earlier referred to as a “plural society” (Furnivall 1948, 304–305).

Figure 1.2. The main road through town with SuperMal Cilegon in the background.

Just beyond the Al-Hadid mosque the main road forks with one branch heading to the west, passing along the southern boundary of the Krakatau Steel factory zone to the factory’s port at Cigading. It then curves to the south toward the beach at Anyer where one can take a speedboat to visit an active remnant of the Krakatau (which in English is often spelled Krakatoa) volcano, which was immortalized in both a Hollywood film and a New York Times bestseller (Winchester 2003). Alternatively, the northwest branch road passes several municipal buildings before continuing on to the factory zone and then to the ferry terminal at Merak. Taking this branch leads one past the new regional parliament that was constructed in the aftermath of Indonesia’s 1999 regional autonomy (otonomi daerah) laws that were intended to decentralize decision making in Indonesia by reducing the influence of the central government (Kimura 2007; Mietzner 2007). Just beyond the parliament, on the right, sits the local police headquarters. Once past this building the traffic speeds up considerably and the road cuts along the edge of the sprawling industrial zone associated with Krakatau Steel. Offices and production facilities sit on the left side of the road, and on the right are located the employee housing complex and company-built recreation facilities. After about half a kilometer the company’s education and training center, where ESQ training sessions were held, is on the left immediately adjacent to Tirtayasa University. The university, named after one of Banten’s preeminent seventeenth-century sultans, was built by Krakatau Steel and offers degrees to local students, mainly in technical fields. Shortly thereafter the main road comes to a four-way stop where one can turn left onto an expansive four-lane road containing far less traffic than neighboring arteries, as it is used only by traffic to or from Krakatau Steel and its adjacent industrial zone. This broad thoroughfare leads, after roughly two kilometers, to the main gates of the factory compound where the primary steel production facilities are located.

Figure 1.3. Krakatau Steel’s main gate with the buses used to transport workers on the right.

Figure 1.4. The interior of the billet steel plant.

Passing through the gates one encounters the first of the six major mills that compose the steel-making facilities at Krakatau Steel. Beginning at the main gate and lined up from north to south these include a cold rolling mill, a wire rod mill, a hot strip mill, a billet steel plant, a slab steel plant, and a direct reduction plant. The steel production process begins at the direct reduction plant, which is most distant from the main factory gate but closest to the Cigading port. Direct reduction is an alternative to coal smelting and involves heating iron ore (imported from Brazil, Chile, and on occasion Sweden) to a temperature of twelve hundred degrees Celsius which destroys impurities and transforms it into sponge iron. The main fuel source in this process is natural gas which arrives at the factory via an offshore pipeline from fields near Cirebon, three hundred kilometers to the east.

After the sponge iron is created it is conveyed to the billet steel and slab steel plants, which are the most dangerous and uncomfortable mills in the entire compound. Here the iron is heated past its melting point in electric arc furnaces and combined with scrap metal, carbon, and other minerals to produce molten steel alloy. The sound of the furnace is deafening, and a fine black carbon dust lingers perpetually in the air creating an oddly diffuse light while coating virtually everything in the factory with a fine, charcoal blanket. The molten alloy is poured from giant black cauldrons into casting machines where it is formed into either billets or slabs. The billets, which weigh between one and two thousand kilograms, are then shaped into bars and rods at the wire rod mill. Adjacent to the billet plant is the slab steel mill where a continuous casting machine is used to create massive slabs weighing between ten and thirty tons. After the slabs have cooled and cured, they are transported across a small roadway to the hot strip mill, an immense and cavernous edifice over half a kilometer long. There they are again heated to over a thousand degrees until they glow bright orange and then are thunderously flattened into smooth sheets of coiled steel.

Like the bars and rods, the hot rolled coils are commodities. They can be fashioned into plates and other objects used in construction and other industrial applications. However, not all are sold, and many of these coils are sent for further forming to the final plant in the production zone, the cold rolling mill. The cold rolling mill was the cleanest and most comfortable plant. In contrast to the other mills it felt almost antiseptic in its absence of dust and other airborne grime and was not nearly as noisy. It had been built most recently and thus had less time to fall into disrepair, as some of the other mills had. A job in the cold rolling mill was a plum position for Krakatau Steel employees, and morale among workers in the mill appeared to be the highest among employees in any of the other plants.

These plants, indispensible to what company officials proudly described as a “fully integrated” steel factory (one that could turn iron ore into commodities), were part of the resuscitation of the steel factory, after construction had gone dormant following the military coup of 1965 and Indonesia’s turn away from the Soviet bloc and toward the West. The period between 1972 and 1995 marked the heyday of Krakatau Steel, as the company and its workers were flush with cash and halcyon fantasies of industrial utopianism. Under the patronage of the longtime minister of research and technology and later vice president, B. J. Habibie, the Suharto government had spared little expense to bring the most up-to-date high technology steelmaking equipment to Krakatau Steel. After construction of the first direct reduction plant in 1972, a series of new plants were brought on line. By 1979 the billet plant and the wire rod mill were completed. In 1983 President Suharto officially opened plants constructed under the company’s “second stage development” plan, including the steel slab plant and the hot strip mill. In 1993, the hot strip mill was expanded and modernized, leading to a corresponding expansion in the organization of the company and more managerial jobs. Suharto again visited the company after a major expansion of the facilities in 1995, when the third direct reduction facility, called Hyl 3, and another slab steel plant were completed (Metal Bulletin Monthly 1996). As long as the company was building new plants, there was a corresponding expansion of managerial positions for employees who had worked at the factory and felt entitled to promotions.

Figure 1.5. The interior of the hot strip mill.

Modernization on the Margins: Faith in Development

Under both Indonesian presidents, Sukarno (1945–1966) and Suharto (1966–1998), national development was seen as a technological problem (Barker 2005). During Suharto’s New Order modernization became a national obsession to the extent that Suharto branded himself “Mister Development” (Bapak Pembangunan). He justified authoritarian political rule based on continually improving Indonesian living standards. Suharto’s influential protégé B. J. Habibie envisioned that the country would import technological innovations to bring about modernization and national development. Habibie’s faith in development was premised on assumptions most notably articulated by Walt Rostow, who argued that individual nation-states move uniformly through discrete “stages of economic growth” (Rostow 1960, 4–16). Operating within this paradigm of modernization, Habibie believed that by importing expertise and modern technology from Europe and North America, Indonesia could leapfrog some of these development stages and bring living standards characteristic of Rostow’s ultimate epoch, “the age of high mass consumption,” to Indonesia.1 Habibie expected that a critical mass of scientists and engineers trained outside the country would return to Indonesia and accelerate the process of modernization (Amir 2007b). Habibie’s optimistic conviction in technology and development was a general characteristic of the developing world during the paradigm of modernization, where massive state-directed investment was expected to raise living standards in the formerly coloniz...