1

“A CRIMINAL COMEDY BUT OF A REVIVALIST SPIRIT”

The Beginning and the End of the Prague Spring

A day after St. Nicolas Day, when the streets were overrun by men posing as St. Nick in bishops’ hats, accompanied by red-horned devils, the Ideological Commission met in Prague. It was December 7, 1964, and the commission, appointed by the Communist Party’s Central Committee, was charged with keeping the lid shut on Pandora’s box of postwar revelations about Stalinism.

As in the rest of the Eastern Bloc, Nikita Khrushchev’s disclosures about Stalin’s crimes had forced the Czechoslovak government to open up its prison doors and send home those political prisoners now known to have been falsely accused. But that had been in 1956. For a decade afterward, the Czechoslovak Communist Party had managed, rather effectively, to stave off the larger consequences of the de-Stalinization that swept through the region. While Stalinism’s victims were being routinely rehabilitated elsewhere, their innocence declared retroactively, Prague remained mute. The Czechoslovak Communist Party rebuffed any attempts at public remembrance and especially the calls for accountability and reform that inevitably accompanied them. At this time the only confessions of guilt, let alone remorse, that the party was willing to make were made securely behind closed doors.

The 1952 Slánský trial stood at the epicenter of the party’s postwar fabrications. It had been one of the most defining show trials of the Stalinist era, replete with memorized scripts co-written by Soviet advisers flown in especially for that purpose and a live radio broadcast of defendants’ confessions and judges’ pronouncements. Fourteen Communist Party leaders and bureaucrats were charged with treason; eleven of them were executed and three imprisoned for life. Of the fourteen accused, eleven were Jewish. Such a statistic suggested that attitudes ripe under Nazi occupation had had currency in communist postwar Czechoslovakia as well, much in the same way that Stalinism and post-Stalinism continued to intertwine. There were no clear demarcation lines yet regardless of who might wish to draw them.

Heda Margolius Kovály, wife of one of those executed in the trials, was among the few “civilians” privy to these initial, closed-door confessions by the Communist Party. In February 1963, the party issued a document that “only carefully selected Party officials were permitted to see” but that Kovály had heard “almost…verbatim by the following day.” In it, the party finally “conceded that all the people who had been convicted at the trials were innocent, that their confessions had been extorted by illegal means, and that during the interrogations a range of brutal and inhuman procedures had been used.”1 For Kovály, a concentration camp survivor, as her husband had been as well, this was all too familiar. Two months later, she was summoned before the Central Committee, where this same document was read out loud to her. She asked whether it would now be made public, to which the party apparatchiks replied, “Out of the question! The Party has decided to handle the whole affair internally. Nothing will be made public.”2 When asked to return with a list of losses that had resulted from the arrest and execution of her husband so that she and her son might be compensated (although on terms favorable to the State Treasury), she drew up a list that included not property but life: “Loss of Father. Loss of Husband. Loss of Honor. Loss of Health.…Loss of Faith in the Party and in Justice.”3 In June of 1963, the party permitted a small notice to be published in the country’s newspapers. It announced that the men executed in the Slánský trial had been rehabilitated. Any more than that still remained off-limits.4

A Young Lady for His Excellency, Comrades!

It was against this backdrop that the Central Committee’s Ideological Commission now met. One of the items on the agenda for this December meeting seemed to be of a more frivolous nature: a theater play written by a popular television writer, Jaroslav Dietl. Titled A Young Lady for His Excellency, Comrades! A Criminal Comedy but of a Revivalist Spirit, it was a light-hearted romp about a financially strapped spa town. After some brief discussion, the commission members unanimously agreed that the play was not to be performed “under any circumstances” because of its “erroneous political orientation.”5 That it had an “erroneous political orientation” was clear to all of them.

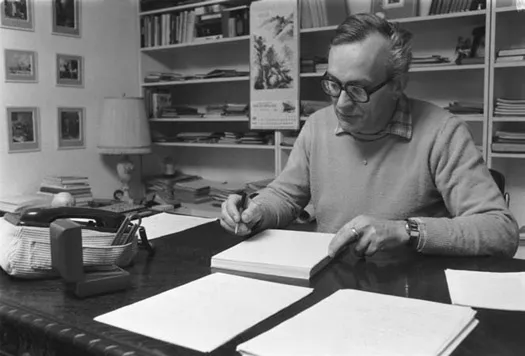

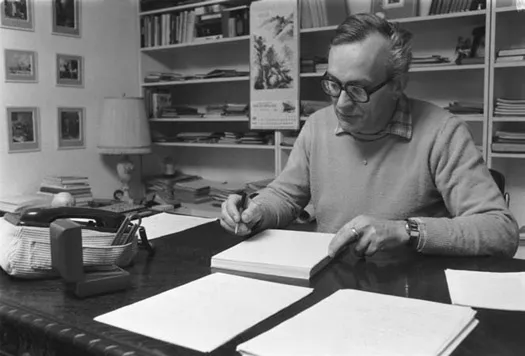

Writer Jaroslav Dietl at his desk, 10 December 1982 (Czechoslovak Press Agency; photographed by Karel Vlček)

To those uninitiated in the subtle balancing act between consenting to de-Stalinization and fending off potential antiparty revolt, the play might have seemed innocuous, belonging merely to the genre of absurdist theater popular at the time. At first glance, it is a play about an acting troupe that, in need of cash, decides to put on some light entertainment because—as they agree—vaudeville sells and everyone is fed up with serious thoughts. The play the actors improvise is set in a fictional spa town that, like them, is bankrupt. When superficial efforts to spruce up its facades fail, the local authorities agree that to survive they must inject capital into the town. They will do this by negotiating a multimillion contract for “our country’s industry” with His Excellency, who, it is implied, rules over a wealthy Arab state. What follows next is a farce that clearly mimics the growing communist crisis in the early 1960s.

His Excellency’s arrival in the spa town is introduced through an official press conference for which the young communist press officer is instructed to follow normal procedure and answer the reporters’ questions by reading unrelated responses from a piece of paper. He successfully does so. But such typically staged public relations begin to run aground as His Excellency makes demands that stretch beyond the parameters of these well-rehearsed gestures and countergestures. First His Excellency requests “a young lady.” Flabbergasted, the town officials weigh their pressing need for foreign currency against their allegiance to official policy stating that the sexual exploitation of women has long been abolished. They eventually agree that while prostitution has died out “as a state-registered business,” the young press officer should go ahead and comply with His Excellency’s wishes. He is sent off to the “club de luxe” with instructions to find “a young lady” and the advice that he must practice what he was taught at the party university: he must “generate policy” as he goes along.

At the club, the press officer is immediately ensnared in a lively discussion about the current economic situation with the husband (also pimp) of a local prostitute. Then, left briefly alone with the wife (also prostitute), he is given an earful of her own financially related marital problems. Her husband, she tells the press officer, wants to expand internationally with the business. “He keeps insisting that we must tear ourselves away from these small Czech standards, and that we must finally show the rest of the world that even we can accomplish something,” she explains. The press officer—responding, according to Dietl’s stage notes, as if he were an employee of the Foreign Ministry—sides with her husband: “I understand where your husband is coming from. We can exist only if we develop in pace with the rest of the world and each one of us has a direct responsibility to know how our field is developing elsewhere—and that counts for you [and your profession] as much as it does for me.” Later he adds, “We have a lot to learn from capitalism on that front.”

The price is set and she is hired as “the young lady” for the visiting Excellency. Since her business is officially illegal, to receive her “honorarium” she is registered as the new director of the Press Office. But it turns out that “with a millionaire’s typical perversity,” His Excellency in fact had wanted a young woman merely to accompany him to official gatherings. The hired prostitute must now be taught certain social skills or, at the very least (as the town authorities agree), “etiquette, modern dance, basic economy, a concise history of the spa people’s liberation movement, and songs and tales from the lives of the spa people.” But with no time even for these basics, she is instructed on how to fend off all potential criticisms. If, for example, she is asked about the bad condition of the roads, her teachers prompt her to “explain how many kilometers of asphalt road there were before the war—the First World War, that is—and immediately it will become clear just how much we have advanced.” When all else fails, she is told, always state the following: “Anyhow, it’s you people who lynch blacks.”

Yet it turns out that His Excellency is interested in a different woman altogether—the chief director of the spa town. She and her colleagues object (presumably to being prostituted by and for the town), but the young press officer insists that this is too important an opportunity for international trade to pass up. She objects further, this time on ideological grounds: “But we’re on the other bank of the river from them, no?” The press officer replies that the whole world is watching to see what they will do and that it is really a question of how far they are willing to step into the water and get wet. Unable to decide for themselves on “which bank of the river” they stand, she orders a call to be put through to “the capital” “because only the capital can decide if we can finally go into the water without getting wet.”

Reading between the Lines

As one might guess, Jaroslav Dietl’s banned play read like a thinly (and for the Ideological Commission not so thinly) disguised allegory of contemporary times. In 1953, Stalin had died; in 1956, Khrushchev had declared Stalin a persona non grata, after which the Hungarians had waged an unsuccessful but embittered revolution; and in 1962, the Stalin statue that had towered over Prague was dynamited out of sight. These events, like the message of the play, would be the lead-up to the 1968 Prague Spring, which, as the Czech-born Oxford historian Z. A. B. Zeman wrote on his first trip back after World War II, was quite different from the “passionate, emotional” 1956 Hungarian revolution. The 1968 democracy movement in Czechoslovakia would prove to be “more of an intellectual exercise. Even under extreme pressure the Czechs and the Slovaks kept their emotions in the background as much as they could. They negotiated, argued, ridiculed.”6 A Young Lady for His Excellency, Comrades! most certainly ridiculed.

Thus Dietl’s play was representative of the times. Indeed, perhaps it was even ahead of its time because, as its subtitle declared, it was of a “revivalist” rather than a revolutionary spirit. But it would have taken the members of the Ideological Commission little time to unravel the play’s multiple meanings and sharp jabs. That prostitution—like so much else—had been eradicated merely on paper but continued in practice not only was true but also represented a widespread hypocrisy typical of postwar communist rule. The laments of the husband-pimp are characteristic of those uttered in the early 1960s by industry managers trapped within the confines of short-sighted policies devised by a centrally planned economy. The responses of the young press officer—spoken in the parlance of the Foreign Ministry—echo the complaints being made by progressive party apparatchiks who soon would drive the reform movement forward. The desire to compete on a world stage was a desire heard during the 1960s within both literary and economic circles. The wife-prostitute is taught the most imperative of diplomatic skills: to fend off valid criticisms with a litany of absurd achievements accomplished under communism (the most ludicrous of which compares the number of paved roads present in the 1960s with the number in the closing years of the Habsburg Empire in the very early 1900s). Sharp reminders of American imperialism and racism are then rolled out as a last resort.

But perhaps what most threatened the members of the Ideological Commission about Dietl’s play (and ironically, it was this same commission that was later accused of encouraging the Prague Spring instead of restraining it) was its ending. The head director of the spa town is unsure by now on which bank she and her cohorts officially stand: do they not represent the bank of the river that is directly across from that of His Excellency? No one is sure any longer. Moreover, do they stick in a toe, a whole foot, or do they plunge headfirst into the river that flows between these two banks (that is, between socialism and capitalism)? Indeed, by 1968, four years after Jaroslav Dietl’s play was presented to the Ideological Commission for review, the Prague Spring reform movement would become centered on this very question: few people wished to swim directly across the river to the other bank, and most intellectuals certainly preferred to stand in the river that flowed somewhere between communism and capitalism. But to do so would prove to be too unstable a balancing act.

Writers as Resisters

As the play also suggests, 1968 found its beginnings in theater. Intimate theater venues, most famously Prague’s Theater on the Balustrades, served up J. Topol’s play The End of the Carnival, which traced the absurdity of local officials implementing collectivization in one small and angry village; Václav Havel’s The Garden Party, which parodied central planning and the planners; and Milan Uhde’s King Vávra, a transparent portrayal of the current party leader, Antonín Novotný, and his uncanny resemblance to an ass. New or else revampe...