![]()

1

A THEORY OF RELIGIOUS RHETORIC IN AMERICAN CAMPAIGNS

Beyond all differences of race or creed, we are one country, mourning together and facing danger together. Deep in the American character, there is honor, and it is stronger than cynicism. And many have discovered again that even in tragedy—especially in tragedy—God is near. In a single instant, we realized that this will be a decisive decade in the history of liberty, that we’ve been called to a unique role in human events.

—President George W. Bush, 2002 State of the Union Address

During the 2004 presidential election, voters chose between candidates advocating starkly different approaches to a myriad of issues of national consequence. The United States was entangled in two costly wars and was still feeling the effects of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Domestically, President George W. Bush and the Congress had just passed major prescription drug reform, enacted controversial tax cuts, and legislated dramatic changes to American education. Yet in the aftermath of the 2004 presidential election, many political observers roundly concluded that Bush’s reelection was not due to any of these factors but was largely the product of Americans’ concern with moral values.

In the months before the election, political observers were already predicting that existing religious and moral cleavages might decide the day. One New York Times headline read “Battle Cry of Faithful Pits Believers against the Rest” (Kirkpatrick, October 31, 2004, 24). The Chicago Tribune reported that “this presidential campaign had become one of the most spiritually saturated in memory with people of faith bombarded with entreaties from Republicans and Democrats” (Anderson, November 4, 2004, C1). The significant role of religion in the election gained considerable support from the Election Day exit polling, illustrating a substantial “God gap” between religious and secular voters. George W. Bush received 64 percent of the vote among those attending religious services more than once a week, whereas Kerry received 62 percent support among those never attending services. Moreover, fully 22 percent of the voting public responded that “moral values” were the most important issue facing the nation, a group of voters that swung decidedly toward the Republican Party (however, see Hillygus and Shields 2005). Asked to interpret this statistic in a Meet the Press interview shortly following the election, Karl Rove characterized these voters as a group of Americans most concerned about a certain “coarseness of our culture.” Voters, Rove argued, saw in President Bush the “vision and values and ideas that they supported” (Meet the Press 2004).

This was not the story of the 2008 election, however. In that election, voters gave comparatively little weight to religious or moral considerations. The day before the election, Stephen Prothero, a religion scholar at Boston University, editorialized that “much of the energy that Democrats and Republicans alike have pumped into the religion question seems to have dissipated. Voters tomorrow will be thinking more about the economy, health care and war than about the social and sexual issues that preoccupied ‘values voters’ in the 2004 election” (Prothero, November 3, 2008, 15A). Exit polls were consistent with this assertion. The Republican support among those attending church more than once a week had been reduced from 64 percent in 2004 to 55 percent.1 The Democratic candidate, Barack Obama, actually won the vote among those attending church “monthly,” a demographic group that John Kerry had failed to capture four years earlier. A Pew study published immediately after the election concluded that, although sizable religion gaps persisted, “Among nearly every religious group, the Democratic candidate received equal or higher levels of support compared with the 2004 Democratic nominee, John Kerry” (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press 2008). And, whereas religion and values were the hot topics on Meet the Press following the 2004 election, these words were not even mentioned on the 2008 post-election roundtable of the program.

Why was religion the story of the 2004 election but not in 2008? The difference in electoral dynamics is puzzling for two reasons. First, in both elections there were other, deeply salient, competing issues that may have distracted voters. Whereas the economy and the first viable African American candidacy may have diverted attention away from religion in 2008, the economy was also highly salient in 2004, along with terrorism, two major wars, and tax cuts.2 But despite these strong similarities in salient secular issues, religious cleavages decided the day in 2004 but not in 2008. Second, there are plenty of reasons to suspect that religion should have been even more important in the 2008 election. For example, 2008 had Sarah Palin, a vice presidential candidate who was in part selected to bring moral and cultural issues to the forefront. Moreover, 2008 was witness to one of the most intense religious campaign issues in recent memory when Obama’s former pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, made controversial remarks at the intersection of religion, race, and politics, arguing that “The government gives [African Americans] the drugs, builds bigger prisons, passes a three-strike law and then wants us to sing ‘God Bless America.’ No, no, no, God damn America, that’s in the Bible for killing innocent people” (quoted in Murphy 2008). Given all this, it is surprising that religion factored more prominently in the public consciousness in 2004 than in 2008.3

We know relatively little about why the influence of religion waxes and wanes from one election to the next, raising ambiguities that operate at multiple levels. At one level, the intermingling of religion and electoral politics raises important normative questions about the nature of political representation in a country characterized as having a “wall of separation” between church and state. When religion is a factor in an election, how should leaders deliver representation to their constituents? Moreover, given the tremendous religious diversity of Americans, is a genuinely inclusive religious representational style even possible?

At another level, religion plays an ambiguous role in U.S. elections because of the varied forms that public religious expression can take. Historically, religious political rhetoric can be roughly classified into two genres. Culture war religious expression generally focuses on deep-seated religious differences in American society and the intractable political conflicts produced by these divisions (Hunter 1991; Evans and Nunn 2005).4 Civil religion appeals, on the other hand, are nondenominational declarations of spiritualized American national identity. Civil religion appeals generally stress points of spiritual commonality among all Americans and posit a transcendent religious ethos that permeates American institutions and culture (Bellah 1967, 1975). Despite volumes of research on these rhetorical genres, we know relatively little about how civil religion and culture war messages are actually received by the public at large. When candidates deploy religious messages, do divisions emerge, or are religious appeals a cultural glue uniting Americans across diverse backgrounds?

In this book, I am principally concerned with the ambiguous role of religious expression and how it comes to shape the American politics. Grappling with this issue will not only explain the role of religion in the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections—it will also help make sense of the meaning of religious and cultural divisions in a country premised on church-state separation. The way in which political elites use religious rhetoric in the public sphere determines the exact role that religion plays in American elections, political culture, and the representative dynamics of the country. At the heart of the argument is the observation that nearly all forms of religious rhetoric can be understood in terms of how they express themselves along two key dimensions: emotion and identity. Religious rhetoric gains its unique political command because it is well equipped to resonate with individuals’ emotions and identities—two factors that, not coincidentally, are central to political persuasion.

The extent to which an election takes on a religious character depends on how successfully elites use religious language to activate emotions and identities. This analysis is not limited to 2004 and 2008. Indeed, I contend that religious rhetoric is an evolving genre that has its emotive and identity-laden roots in early Puritan sermonizing and Revolutionary pamphleteering. The success of the genre is due to its use having been so congruent with basic psychological persuasive properties and its being flexible enough to fit with the religious sensibilities of an incredibly varied religious constituency. The religious character of American politics—both now and throughout history—depends on how well religious political rhetoric activates the emotions and identities of a diverse and deeply religious public. Moreover, the activation of religious considerations has consequences that extend far beyond electoral outcomes. The religious nature of political debate and discussion ultimately shapes the nature of political representation and the contours of the political community. As we will see, American civil religion has a special place in this story. Civil religion rhetoric can simultaneously be an electorally powerful persuasive tool and point of shared religious identification, and also a source of alienation from the political process.

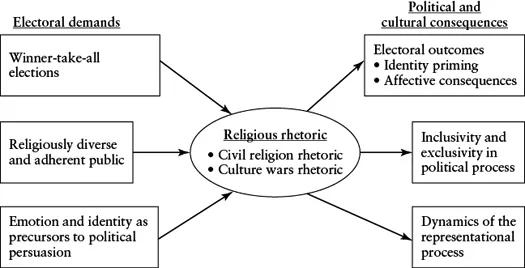

THE PERSUASIVE APPEAL OF AMERICAN CIVIL RELIGION

In this chapter, I elaborate a theoretic framework for how religious rhetoric intensifies the emotions and identities of the American public and what the consequences of these rhetorical choices are. Doing so requires knitting together several diverse strands of scholarship, encompassing research on religion, voting behavior, political communication, and social psychology. The basic argument, illustrated in figure 1.1, has several moving parts. The religious character of American politics is shaped by a confluence of three factors: the religious makeup of the U.S. electorate, the psychological basis of persuasion, and the political demands imposed by competitive winner-take-all elections. Religious rhetoric (particularly the civil religion genre) is uniquely adept at satisfying the demands imposed by each of the factors, enabling candidates to form deep connections with voters in competitive electoral environments. Moreover, when specific forms of religious rhetoric are strategically deployed by candidates, the consequences extend far beyond the realm of any single electoral contest. Precisely how candidates locate themselves at the intersection of these factors not only determines their electoral success but also has implications for defining the boundaries of the American political community and for shaping the dynamics of the representative process.

FIGURE 1.1 Causes and consequences of religious political rhetoric

How religious rhetoric connects electoral demands to political and cultural consequences. The dominant forms of religious political expression are the results of a confluence of political, religious, and psychological factors. In turn, these forms of expression have consequences on electoral behavior and American political culture.

Psychological, Religious, and Political Factors in American Elections

As figure 1.1 illustrates, candidates making their case before the American public must deal with multiple crosscutting pressures, the first of which is political. Most U.S. races are winner-take-all, meaning that to hold office a candidate must win a plurality of the votes (or a majority of electoral votes at the presidential level). Unlike many other electoral systems, seats are not allocated for second place. Accordingly, candidate rhetoric must appeal to an audience that holds a diverse array of religious beliefs. The United States is unique among world democracies in this regard, having both high levels of religious adherence and no single dominant sect (Greeley 1972; Pew Research Center for the People and the Press 2007; Putnam and Campbell 2010). Thus, candidates cannot afford to ignore religion, nor can they afford to privilege a particular faith tradition.

These political and religious pressures have an interesting point of intersection with what is known about the psychological basis of political persuasion. As previously noted, political psychologists have identified two factors—identity and emotion—that play a central role in how voters think about political candidates. While many factors can awaken emotions and identities in the public, religious appeals are particularly well suited to this task and are at the same time capable of effectively satisfying the competing political and religious pressures incumbent on candidates.

By identity, I refer here to “social identities,” or individuals’ awareness of objective group membership and the sense of attachment they get from belonging (Tajfel 1981; Conover 1984, 1988). Although “being religious” need not imply social identity as a matter of definition, scholars have recognized that religion does play important identity-relevant functions (Emmons and Paloutzian 2003).5 Social identities have been found to have numerous political implications, the most consequential and widely replicated being ingroup favoritism, even when group attachment is fairly minimal (Huddy 2001). That is to say, even when group boundaries are arbitrarily assigned, individuals still tend to demonstrate a persistent bias toward their own group. And, because religious group attachment is far from arbitrary, religious social identities should engender substantial favoritism toward those with whom the individual shares group membership.

Candidates commonly use political rhetoric to prime identities. Priming refers to “provok[ing] opinion or behavior change not because individuals alter their beliefs or evaluations of objects, but because they alter the relative weight they give to various considerations that make up the ultimate evaluation” (Mendelsohn 1996, 113). In any given election, voters have numerous competing considerations, from issues to images to social group memberships (Valentino 1999; Druckman and Holmes 2004; Druckman, Jacobs, and Ostermeier 2004; Jackson 2005). By rhetorically emphasizing social identities (or any number of other considerations), candidates make these group attachments a salient basis of political evaluation. In this way, expressions of religious identity can create deep feelings of group favoritism between candidates and the public.

Of course, candidates can make direct appeals to denominational subgroups (such as Catholics and Baptists) even though, with no single dominant religious denomination in the United States, subgroup appeals have a somewhat limited audience. What is more likely is that religious identity priming operates by engendering a sense of civil religion identity. The concept of American civil religion asserts that a broad religious identity unites virtually the entire nation. In this way, civil religion appeals should theoretically serve as a solution to the challenge of appealing to a religious constituency that is both committed and diverse. With the possible exception of appeals to national identity, no other group-based appeal (e.g., to race, gender, or class) has the potential to codify political support around such a broad (yet salient) group. Thus, when Bush said (see quotation at the outset of this chapter) that “God is near. In a single instant, we realized that this will be a decisive decade in the history of liberty, that we’ve been called to a unique role in human events,” he was asserting a leadership role in an overarching spiritual community.

Scholars emphasize different points regarding precisely how public expressions of civil religion should be characterized and where it gains its cultural and political significance. For example, Martin Marty (1987) identifies both “priestly” civil religion, which is primarily concerned with legitimizing state practices, and “prophetic” civil religion, which seeks to guide the nation to meet certain ethical benchmarks (see also Wald and Calhoun-Brown 2006). Whereas Marty ascribes an ongoing sociological significance to both forms of civil religion in American politics, others have suggested that the cultural force of civil religion has declined since a peak in the 1950s (Ahlstrom 1972; Marty 1987). Other scholarly debates revolve around whether civil religion sits in tension or in harmony with religious pluralism. Some argue that civil religion can unite common elements of different religious traditions; others contend that it carries with it an implicitly sectarian impulse (Lambert 2008, 26–27; see also Mead 1974). Taking up this latter point, Herbert Richardson concludes that, in the end, “civil religion always tends to generate the very situation it seeks to prevent” (1974, 165).

I address these debates in this book. The theory of identity priming, however, suggests a somewhat different starting point for grappling with language of civil religion an...