CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The uskoks of Senj are the heroes of one of the cycles of South Slav folk epics, but they are not simply the stuff of legend. The archives and the histories of nearly all the cities and states that rimmed the Adriatic in the sixteenth century are filled with references to these sea and land raiders who served as irregulars in the Habsburg border garrison in Senj for almost a century. The uskoks aroused strong and contradictory emotions among their contemporaries. The Habsburg archdukes and the Emperor, with papal support, hailed the uskoks for their role as a bulwark of Christendom, crediting them with preserving Europe from the onslaught of the Turk. Fra Paolo Sarpi, the contemporary Venetian theologian and historian, denounced them as pirates and brigands, echoing the opinions of the Venetian officers responsible for the security of the Adriatic and the anxious merchants who saw their ships off with the phrase “God preserve you from the hands of the uskoks of Senj.” Although the rural populations along the borders—Ottoman, Venetian, and Habsburg—left little of their own testimony, clearly the uskoks received their most consistent support from these people, in spite of all prohibitions and in spite of the fact that in the long term they probably suffered the most from the uskoks’ raids. Long afterward the peasants and pastoralists of the border preserved vivid memories of the uskoks in epic songs about their bravery, their often bloody deeds, and their rigorous code of honor, glorifying them as heroes and symbols of freedom from all authority.

The uskoks have continued to draw the attention of historians, whose assessments have been no less contradictory than were those of contemporaries. But despite this constant interest, surprisingly little attention has focused on the uskoks themselves and their own perceptions of their role. Who were these men, and why did they provoke such violently contrasting opinions? This book attempts to answer these questions.

The Uskoks of Senj between Three Empires

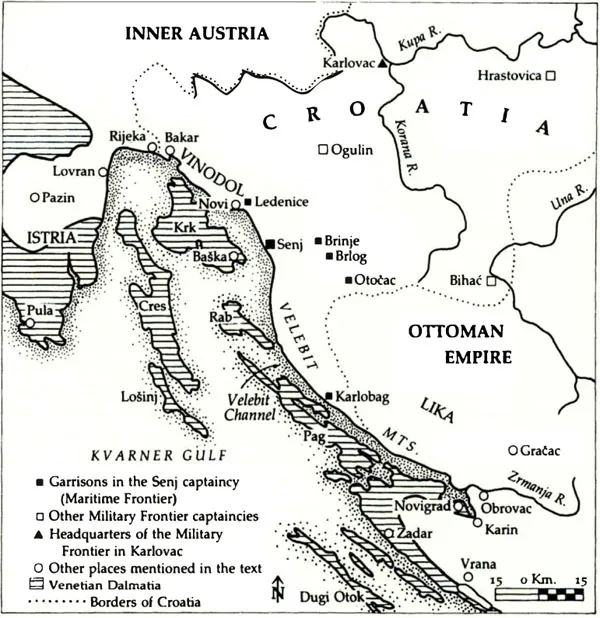

The uskoks developed as a military community where the borders of three empires met on the shores and hinterland of the Adriatic. In the eyes of the Republic of Venice, the Adriatic of the sixteenth century was a Venetian sea—its “gulf.” The Republic’s possessions edged much of the eastern shore, from Istria south to the Bay of Kotor, each city commune surrounded by its small circle of protective territory, while the Adriatic islands as far as Korčula stood like a stationary fleet off the Dalmatian coast. But by the early sixteenth century the Serenissima’s Dalmatian hinterland had fallen to the Ottomans. As far north as Lika, the hinterland was held in the firm grasp of the Turk—in many places Ottoman territory was within eyeshot of city walls—and Venice’s possessions were open to any Ottoman attack. The Ottoman advance had stopped short of the Kvarner Gulf (Quarnero). After 1526 the stretch of territory south of Rijeka and north of the Zrmanja, a part of the reliquiae reliquiarum of once-powerful Croatia, was held by the House of Austria, inheritor of the crowns of Croatia and Hungary. This Croatian Littoral and its hinterland formed the nucleus of the Habsburg Military Frontier system against the Turk, the maritima confinia. Here, at various fortress towns defended by military captaincies, the Habsburgs stationed troops of regular and irregular soldiers. (See Maps 1 and 2.)

One of these, on the barren karst coast at the foot of the Velebit mountains, and situated beneath a mountain pass that channels the bora, the furious northeast wind, was Senj. In the sixteenth century it was a small town, surrounded to the distance of a mile or two by a dense forest that, together with the high mountains at its back, cut off any attack from the land. It lacked a protected harbor, so that as a contemporary noted, the barks and small craft had to be “drawn onto land before the gate of the city, and tied and anchored as though they were at sea, otherwise the bora that comes up suddenly there would carry them away.”1 For almost a century this was the principal resort of the uskoks.

The Ottoman invasions of the Balkan Peninsula with their plundering raids and destructive skirmishes set large portions of the population in motion. Many crossed the frontier to take refuge in the territories of neighboring states. Some formed units for defense or retaliation against the Ottoman enemy, often clustering around the border fortresses. These refugees were known by various names: prebjezi, Vlachs, uskoks. Although at first used generally as a term for refugees (the word itself derives from the Croatian verb uskočiti: to jump in), in time the term “uskok” came to be applied especially to those who settled in Senj as border irregulars, and was eventually extended to all citizens of Senj (although they themselves rarely used the word). The uskoks, most of whom received no pay, were largely dependent on plunder for their livelihood (and the fact that they so supported themselves without further draining the empty coffers of the Frontier authorities, and indeed paid a portion of their booty to their military commanders and to the Habsburgs themselves, made them particularly attractive as border troops).

1. Croatian Military Frontier, c. 1579.

Uskok raids across Ottoman territory took two main forms: directly south into the Lika area, which bordered on the territory of the Habsburg captaincy centered in Senj; and into the Ottoman hinterland of Dalmatia, which could be reached only by sea, and by crossing the territory of Venice or the Republic of Dubrovnik (Ragusa). In conventional military maneuvers, carried out under the leadership of border officers, the uskoks could number as many as two thousand. More often, however, they set out in smaller bands, some ten to thirty in a company, under the command of one of their own leaders. During raids lasting weeks or months, the uskoks lived off the land or what they could capture, ambushing merchant caravans or Ottoman border troops, plundering cattle and taking prisoners for ransom.

Very early, the uskoks extended their raids to the shipping of the Adriatic, plundering Ottoman merchants and their goods. These goods were increasingly carried on Christian vessels and formed an important part of the Adriatic trade. They were often carried on Venetian ships, but other merchant fleets, such as those of Dubrovnik and Ancona, also carried Ottoman goods. Claiming the right and the duty to plunder the goods of the infidel, uskok bands in their small light barks ambushed shipping in Dalmatia’s ports and coastal waters and ransacked cargoes for merchandise belonging to Turks and Jews. Christian merchants, too, inevitably suffered losses in these raids. With their limited numbers and small primitive craft it is hard to believe that the uskoks could have posed the threat to shipping that they did, yet fear of them was a factor that led Venice to send its great galleys to guard the merchantmen that sailed north from Split, carrying the trade that had arrived overland from the Levant.

Uskok raids came to be a serious irritant to Venice, for they disturbed relations with its Ottoman neighbors, relations Venice was anxious to keep peaceful. While the Republic was at war with the Porte (1537–39 and 1570–73), the Signoria encouraged uskok actions against the Turk and engaged uskoks in the Venetian forces. In peacetime, however, Ottoman authorities seized on uskok actions as an opportunity to complain to Venice over the alleged complicity of Venetian citizens in these attacks and threatened to send in their own fleet if Venice could not secure the waters of the Adriatic, as guaranteed in the Ottoman-Venetian treaties of 1540 and 1573. Similar considerations troubled the uskoks’ relations with Dubrovnik, which found itself, as a Christian city under Ottoman protection, in an awkward position between the Porte and the uskoks.

The Signoria’s repeated response was both to oppose the uskoks directly with orders forbidding cooperation between uskoks and Venetian subjects in Dalmatia and limiting their operations in the Adriatic, and to attempt through diplomacy to force their Habsburg masters to rein them in or remove them from Senj entirely. Attempts to halt cooperation between the uskoks and the people of Venetian Dalmatia were fruitless, although Venice renewed its decrees regularly, adding ever more horrible punishments. Venetian approaches to the Habsburgs were also ineffective. At the court of the Archduke of Styria in Graz, the spectacle of Venice embroiled with the Porte was not unwelcome. Furthermore, the Habsburgs countered any complaint about the uskoks with a demand for free navigation, fueled by their resentment of the Republic’s pretensions to Adriatic supremacy. The Signoria’s complaints usually had a more sympathetic hearing in the Emperor’s court in Vienna, especially because the Ottomans threatened reprisals against the Habsburg borders for uskok attacks, but any serious move to replace the Senj garrison was hindered by the Archduke’s plea of lack of means. The frequent Habsburg commissions to Senj did little more than return a fraction of the most recent plunder and once again prohibit unauthorized raiding across Venetian territory, to small effect.

The escalation of Venetian attacks on the uskoks and blockades of the trading ports of the Croatian Littoral from the 1590s eventually forced the Habsburgs to make some concessions to the Republic by restricting the liberties of the uskoks. With the end of the Habsburg-Ottoman Long Turkish War in 1606, the Habsburgs, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice were all formally at peace. Raiding and acts of war were forbidden to all sides. The Habsburgs now increasingly viewed uskok actions as a liability, and strictly prohibited unauthorized raiding, but they did not provide subsidies to the Senj garrison to make up for the loss of booty.

Inevitably, uskok raids continued. Still irritated by both the raids and Ottoman complaints, the Signoria took advantage of its strong alliances and the Archduke’s domestic difficulties to act decisively against Senj and its protectors. The Venetian fleet blockaded the Littoral against shipping and uskok expeditions, and eventually declared war against the Habsburgs in November 1615—”the Uskok War.” With the Venetian troops unable to consolidate their early victories, and with the Archduke distracted by the prospect of inheriting the responsibilities of the Empire, a peace was negotiated in Madrid in 1617, by which the Habsburgs agreed to remove the uskoks from Senj and burn their ships. The uskoks of course protested, but by the end of 1618 many of them had been moved to the interior of the Croatian Military Frontier. Small independent uskok operations continued through the 1620s, from both Senj and the surrounding areas, but with the Venetian-Ottoman wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the focus of new uskok activity shifted to the Venetian military border in Dalmatia.

The uskoks of Senj were not forgotten, however. In the vocabulary of the Venetians, ‘uskok’ remained so firmly linked to the corsairs of Senj that they avoided using the term for the refugees who made up their own Dalmatian militia in the Candian and Morean wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, though their Ottoman adversaries had no doubt that they were being raided by uskoks. Nor did the border population forget the uskoks, spreading their fame far beyond the Adriatic hinterland through the epic songs that preserved the memory of their exploits. The great popularity of these songs only a little more than a century after the expulsion of the uskoks from Senj can be seen from the large number included in the first substantial collection of these oral epics, the Erlangen manuscript, written down in the early eighteenth century.2 Tales of the uskoks continued to compel the imagination into the twentieth century, not only in oral literature but also in plays, novels, and scholarly monographs.

Approaches to the Uskoks

One explanation of the contradictory assessments of the uskoks lies in the varying purposes for which they have been used. Most considerations of the uskoks, beginning with contemporary observations and continuing to the present day, have concentrated on the three great empires that met in the Adriatic and have seen the uskoks’ significance in the context of the interactions between these powers. The conflicts over the uskoks provide an admirable device through which to focus on the shifting relationships of Venice, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.3 Such studies have usually concentrated on great power relations, treating the uskoks only inasmuch as they were the occasion of conflict. Indeed, most have centered on Venice’s economic and territorial interests in the Adriatic, and the threat, both direct and indirect, posed to these interests by the uskoks (and behind them the Habsburgs and the papacy). Too often interpretations of the uskoks’ motives in such studies have been based on the consequences of their actions for the Republic: because their raids, though ostensibly directed against the infidel, also harmed Christian interests, the uskoks must necessarily have been hypocrites, concealing their lust for booty behind a facade of religion. Much of the reality of uskok life has found no place in these interpretations because it casts little light on the Venetian-Habsburg rivalry.

A second approach to the uskoks treats their story as one of resistance to oppression by alien powers, a struggle against Venice and the Turk. Much of this writing is rooted in the nineteenth-century romantic rediscovery of the national past of the South Slavs.4 Here too the conflicts between Venice, the Habsburgs, and the Ottoman Empire provide the frame of reference, and the uskoks’ significance is derived from their relations with these powers. This historiography has paid more attention to the uskoks’ motives (usually defined as national and religious), though the projection of contemporary political concerns onto the past sometimes mars its value. Such studies have increased our knowledge of uskok actions by sifting through the sources to build up a narrative of battles and raids, usually focusing on uskok military prowess against Venetian forces and, in less detail, against the Ottomans.5 This concentration on the objects of uskok attack, however, has been at the expense of an understanding of the internal development of the uskok phenomenon.6

Neither of these approaches is completely satisfactory in helping us to understand the uskoks and their place in the sixteenth-century Adriatic borderlands. The economic, political, and religious competition between the three empires that met in the Adriatic was the fundamental condition for the existence of the uskoks: it created the niche they exploited so successfully for nearly a century. Yet the relations between these powers are not in themselves sufficient to explain all aspects of the uskoks’ history. Nor is it possible to see the uskoks simply as the ...