1

GREENING NEW YORK CITY

Political Economic Context and Environmental Stewardship from 1970 to the Present

Following the political ecology traditions of “progressive contextualization” and tracing “chains of explanation” or “webs of relations,” this chapter places the production of nature in New York City in a broader context (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987; Vayda and Walters 1999; Rocheleau 2008). While the long arc of New York City’s political-economic history extends over centuries to include its precolonial, colonial, mercantile, and industrial periods (see, e.g., Burrows and Wallace 1999), the most crucial era to consider for its influence on contemporary forms of urban nature began in the 1970s. This period was characterized by postindustrial restructuring and transformation that has shaped New York’s role as a global city in a globalized economy (Sassen 2001; Savitch and Kantor 2002; Sites 2003). Numerous scholars consider New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis as a political-economic turning point locally and globally, as part of the cyclically crisis-prone nature of capitalism (Shefter 1985; Sites 1997; Polanyi 1944 [2001]; Jessop 2002; Harvey 2005).

In studying this postindustrial shift, regulation theorists identified changes in urban governance, arguing that a transition from national, state-led government to multiscaled, networked governance occurred, involving both (1) an expansion of actors in the decision-making arena, and (2) shifts in the scales of those arenas (Harvey 1989; Jessop 2002). Regarding the expansion of actors, private sector and civil society actors play crucial roles in political decision-making, thereby changing the role of the state (Bulkeley 2005). The retreat of the state has been understood as a “hollowing out” (Jessop 1994, 2002) or as a “shadow state”—where civil society takes on state functions (Wolch 1990). Perkins (2009) argues, however, that the “shadow state” concept is less applicable to environmental management than it is to social services, for environment quality was never an entitlement in the way that welfare was, and it has always been an area of localized governance and state–civil society interaction.1 Thus, it is clear that public, civic, and private actors are all shaping the urban sphere, but we can question whether the expansion of actors is anything new or whether the metaphor of hollowing out is completely fitting in the case of urban nature. Regarding shifting scales, there has been concurrent upscaling (as in the creation of the European Union) and downscaling (as in the rise of cities and regions in policy innovation) (Swyngedouw 2005; Gustavsson et al. 2009). Harvey (1989) argues that this shift has driven a change in the strategies of urban governance from “managerialism,” focused on the provision of social services, to “entrepreneurialism,” focused on interurban competition. Local sustainability initiatives like PlaNYC can thus be understood in the context of competitive, global cities engaging in city image-making through sustainability planning and investments in environmental quality (While et al. 2004; Gibbs and Krueger 2007; Jonas and While 2007). While examining the practices of local politics is crucial to understanding municipal sustainability planning, scholars remind us not to privilege a single scale and to place local phenomena in broader temporal and spatial contexts, which I do in this chapter by drawing upon secondary literature on the evolution of the governance of urban nature in New York since 1970.

In addition to this brief historical review, my own approach to understanding the governance of New York’s urban environment draws upon survey results, Social Network Analysis (SNA) data, and key informant interviews.2 SNA is a quantitative method rooted in graph theory that provides a way to analyze complex networks (Wasserman and Faust 1994).3 Using SNA to examine local “ego networks,” one can begin to understand the relations between actors and the relative positioning of these actors in their local networks (Wellman 1979; Marsden 1990; Scott 2000; Burt 2007; Connolly et al. 2013). In New York City, there is a large, polycentric network of civic groups working on a range of site types across differing neighborhoods helping to steward urban nature (Connolly et al. 2014). A subset of these civic organizations is playing a crucial brokering role in the network, helping to share resources and information across sectors and scales (Connolly et al. 2013). Indeed, most of these broker groups were founded in the post-1970s era and persist to the present day. Finally, with this political-economic and civic stewardship network data as background, we can then examine the contemporary governance networks involved in urban forestry and agriculture, which provides an overview of the actors and relationships described in subsequent case chapters.

Political Economic History: New York City’s Urban Nature from 1970 to the Present

It is important to note that many of the federal policies that helped encourage the suburbanization of the country and the form of New York City’s open spaces precede the fiscal crisis and date to the Depression and prewar years.4 So, too, did the Robert Moses era of top-down, centralized, car-dependent planning and road building leave an indelible mark on the New York City landscape. Moses’ legacy includes many of the parks and beaches in the city and region—as well as the parkways, highways, and bridges connecting these sites (Caro 1975; Gandy 2002). Brecher et al. (1993, 13) attribute many of DPR’s ongoing budgetary challenges to the “mismatch” between the size of the park system, expanded under Moses with substantial federal support, and the limited local resources available to maintain it since that time.

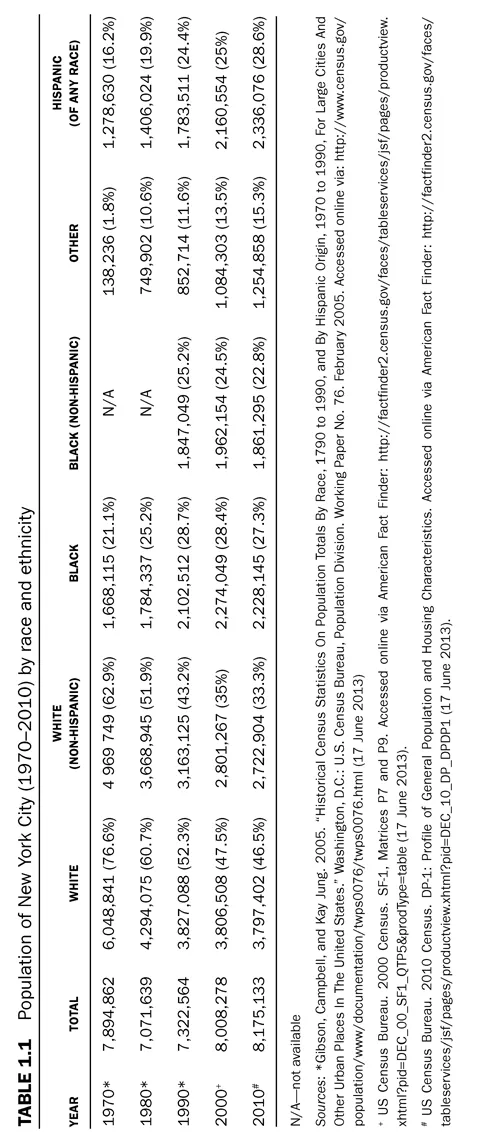

From the 1970s, New York City faced declines in the manufacturing base, the rise of the service economy, a rapid population outflow to suburban areas (particularly among whites), a decline in the municipal tax base, and widespread housing abandonment and arson (Mollenkopf and Castells 1992; Sullivan 1992; Brecher et al. 1993; Gandy 2002; Harvey 2005; Berg 2007). Even with substantial continued immigration to the city, the overall city population declined from 1970 to 1980 and did not rebound until the real estate and development boom of the 1990s (NYC DCP 2011). These changes fundamentally reoriented the spatial organization, demographic patterns, and social structure of the city. Table 1.1 shows New York City’s total population and racial and ethnic composition over the period 1970–2010.5

In the 1970s, sustained municipal budget deficits coupled with borrowing for municipal operations nearly led the city to default on its loans. This near-bankruptcy had major consequences for city governance through the creation of new public authorities that were not responsible to the electorate (Shefter 1985). Shefter’s (1985) detailed analysis of the fiscal crisis reveals that its origins were as much political as economic; for mayoral candidates to succeed in being elected, they had to put together grand, multiracial, multiethnic, cross-class coalitions that supported municipal spending on public wages, services, and capital projects. Postcrisis, when the federal government refused to offer New York City a key bailout (although it later acquiesced), the New York Post headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead” epitomized the sense that the city was being left to its own failures (Shefter 1985; Roberts 2006). Overall, Brecher et al. (1993, 10) identify four periods of distinct policy and budgetary regimes in New York City from 1960 to 1990 and three main factors contributing to these changes: “the performance of the local economy, intergovernmental interventions, and power relations among local interest groups.”6

While other urban scholars have focused on housing policy and local development practices (Sites 1997), I examine the ways in which the economic downturn influenced the production of nature in New York City. One commonly cited consequence for open space management was the way in which massive budget cuts led directly to declines in the staffing, maintenance, and safety of New York City’s parks, including sustained challenges with addressing graffiti and vandalism throughout the 1970s and early 1980s (Brecher et al. 1993). Most visibly, planned capital investments in Central Park that were called for in a 1973 master plan were postponed (NYC DPR 2013a). In 1974, as a strategy to ease the park maintenance burden, the city transferred more than thirteen thousand acres of land around Jamaica Bay and the Staten Island coast to the National Park Service, land that now comprises the federal Gateway National Recreation Area. Overall, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation’s (DPR) operating expenditures underwent a fairly steady decline from 1975 to 1984, with an increase in the budget in the second half of the 1980s (Brecher et al. 1993). Gandy (2002, 104) describes the impact of such long-term declines in municipal funding, leading to vastly unequal access to public space throughout the city: “By the early 1990s New York ranked nineteenth among major American cities in terms of per capita public expenditures on its park system (far below Los Angeles or Chicago, for example) and was left with just half the park staff it had in 1960.”

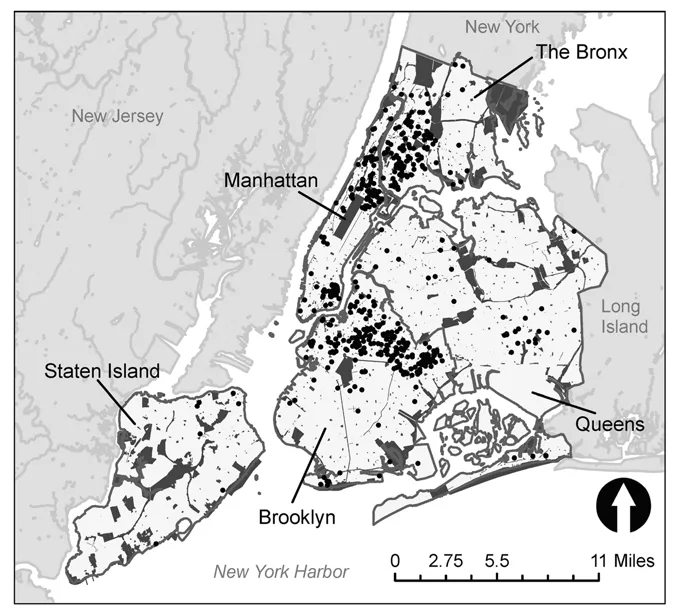

At the same time, economic decline and housing abandonment also triggered a rise in community gardening practices (Francis et al. 1984; Lawson 2005). Many of the thousands of vacant lots across the New York City landscape of the 1970s and 1980s—particularly in the South Bronx, Lower East Side, and Bushwick—were the result of arson (Sullivan 1992). Intrepid residents worked to reclaim vacant lots, fight back against drug sales and prostitution, and create neighborhood green spaces. The more than five hundred gardens currently in New York City display a spatial distribution informed by the disinvestment of the 1970s (see Map 1.1). The individual efforts of gardeners are well-documented within the contemporary discourse of community gardens. What is perhaps less explored are the network of civic organizations and institutions that emerged out of this period to support gardening and greening efforts, which are further discussed in the section on civil society.

The 1980s and early 1990s saw the continued rise in inequality across New York City, with the metaphor of the “dual city” encapsulating the differences between Wall Street, yuppie elite, and the low-income communities of color ravaged by disinvestment, crack cocaine, and AIDS. This economic period of the dual city saw the political transition from Mayor Ed Koch (1978–1989) to the first African American mayor of New York City, David Dinkins (1990–1993) (Mollenkopf and Castells 1992). In 1989, the rape and brutalizing of a white woman in Central Park, allegedly by a group of African American youths (who were exonerated decades later by DNA evidence), came to serve as an incredibly racially divisive moment in the city—and furthered the sense that New York City’s parks were unsafe (Knight-Ridder newspapers 1989; Mollenkopf 1992;Filipovic 2012).7 At the same time, the city was able to increase its capital spending on parks and open space, starting in the 1980s. According to a history of the NYC DPR: “As the city reentered the municipal bond market in 1981, Mayor Koch issued his first ten-year capital plan. The plan proposed a $750 million commitment to rebuild the city’s parks. For the first time in years, the Parks Department was also building up its permanent work force, which had fallen to under 2,500 workers in 1980 from over 5,200 in 1965” (NYC DPR 2013a). This mayoral and agency commitment was mirrored by the support of local community boards for parks and open space, which made park maintenance their number one priority—surpassing police patrols for the first time in 1986 (NYC DPR 2013a). The spatial inequalities in the way that parks were managed also helped to catalyze the local environmental justice movement in New York City to focus on access to quality open space as a crucial area of concern (Francis et al. 1984; Fox et al. 1985).

MAP 1.1 Map of New York City’s parks and community gardens. Created by: Michelle L. Johnson, U.S. Forest Service. Data sources: Greenthumb. 2013. New York, NY: New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Available via: https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Environment/Greenthumb/86sd-4yhi. (September 10, 2013); Parks. 2013. New York, NY: New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Available via: https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/Map-of-Parks/jc79-4imn. (September 10, 2013); U.S. GDT Federal Park Landmarks. 2002. Redlands, CA: ESRI and Geographic Data Technology, Inc.; New York City State Parks. City of New York, NY.

The development boom of the mid- to late 1990s was coupled with and encouraged by the Republican mayor Rudolph Giuliani (1994–2001) (Sites 1997; Berg 2007). Giuliani emphasized aggressive enforcement of “quality of life” violations (loitering, drunk and disorderly, jay walking, graffiti) in ways that were praised by some for reducing crime but also criticized as anti-homeless, intolerant, and racist (Smith 1998; Grogan and Proscio 2000). Inspired by James Q. Wilson’s “broken window theory,” Giuliani argued that these smaller violations led to a disordered public sphere that signaled a lack of caring and invited further, more serious crimes (Wilson and Kelling 1982). This administration was notoriously prodevelopment, with Giuliani criticizing community gardeners as “stuck in the era of communism” (Lefer 1999). When the mayor attempted to auction off several hundred garden sites for housing development, this triggered a community garden crisis that is described in chapter 5. In this period, New York’s urban nature was also shaped by Henry Stern, the eccentric commissioner of the DPR from 1983 to 1990 and 1994 to 2000. A 1995 New York Times profile described Stern’s leadership under Giuliani: “Mr. Stern . . . presides over a Parks Department that has been under siege for 25 years. He battles daily to save an empire of 1,500 properties and more than two million trees from further budget cuts at a time when layoffs will soon reduce his roster of full-time workers to a record low of 2,400. He had twice that many when he was Parks Commissioner in the last decade. . . . Today, under a Republican mayor, he must manage the citizens groups and donors who help the parks in lean times” (Bumiller 1995). Overall, Giuliani established a revanchist form of governance that reduced taxes, cut public services, and heavily policed the streets of New York, serving certain citizens (white, wealthy), while ostracizing and criminalizing others (homeless, poor), and transforming the public realm in the process (Smith 1998; Harvey 2005; Be...