![]()

1

We Don’t Have Enough Water to Make Tears

Surviving the Earthquake, or Not

January 2010

“Oh, hey, you haven’t wished me happy new year yet.” That’s what saved the Catholic leader’s life, twelve days into a year that had had about as much happiness as it was going to get.

Monsignor André Pierre, rector of the University of Notre Dame of Haiti, was racing to a meeting at the archbishop’s office next to the pink and yellow National Cathedral. “I waved to the archbishop up on the gallery from below and then I started running up the stairs,” he said. Then someone stopped him for that new-year greeting:

At that second everything went black. I thought I was having a heart attack. I shifted to the left, I shifted to the right, and then I went up in the air. Then the building fell on top of me. I said, “André, move.” I rolled and crawled. I couldn’t see anything; it was black. It was like being underwater, except it was earth. I ate so much dirt I can’t tell you. It took me about forty-five minutes to get out. You couldn’t see my clothes, my face, anything; I was just one solid mass of earth. Someone came by and wiped my face off and said, “Oh, it’s you.”

The archbishop and the other monsignor who had been awaiting him to start the meeting were both killed.

There were wounded people everywhere. I shouted “Bring the wounded!” I couldn’t open the driver’s door of my car; cement blocks and debris and a beam had fallen on it. But I got in through the passenger door. We loaded up five or six people to take to the hospital, but there was no more hospital. So I took them to [the neighborhood of] Delmas, and we set up a clinic there. I called my brother who’s a doctor, and he told us how to clean the wounds.

Everyone can tell you an epic story of survival, their own or someone else’s. Monsignor Pierre worked with a young computer technician, Kertus Viaud, who lived to tell this one:

I felt the ground shake and I knew an earthquake was coming. I’d heard you were supposed to get under a solid structure, but the best I could do was jump into my baby’s cradle. When the shock hit, it turned the cradle sideways and shot me out into the air.

I landed and was about to run, and then I suddenly had the idea that if I ran, I could die. I stopped and let the dust settle until I could see, and that’s when I saw that I wasn’t on the ground, I was on a roof. If I had run, I would have fallen off and maybe died. I was standing there in just my boxers, still holding my cell phone I’d had in my hand when the event happened. I pulled two big shards of glass out of my feet that I hadn’t even felt.

That night I slept on the sidewalk without a sheet or anything. The next night, I was sleeping on [the boulevard of] Champ de Mars when they said there was a tsunami coming. Everyone was yelling, “The water is coming!” We jumped up, but the man next to me didn’t move, so I shook his shoulder and told him, “Hey, come on.” That’s when I realized he was dead.

Deriva Antoine, a young woman who had been a street vendor before she lost everything she had to sell, recounted: “When the earthquake struck, I bent over my baby like this.” She crouched and braced, arms crooked. “I said, ‘Even if I die, this little baby is going to live.’ ”

Josette Pérard, Haiti director of the grassroots development foundation Lambi Fund, shared this story:

Right in front of us a wall started to fall. Our driver veered really fast to the right, and the building fell where we had just been. That driver saved my life.

It was rush hour and the street was packed. A lot of cars all around us got crushed. They took a child out of the car in front of us and I thought for sure it was killed. But the child was so small, it came out alive.

Houses were falling left and right. I heard people screaming. A woman who’d just been pulled out of a house was lying on the ground bleeding, shouting, “Help! Help!” I said to two policeman, “Call an ambulance for her.” Those police were going crazy; they had family somewhere, too. They said there was nothing they could do, which was true. There was no way an ambulance could get through; the earthquake had thrown cars into the middle of the street.

A little schoolgirl was in shock, panicking. She came to me sobbing, asking for my phone so she could call home. She called and called, but no telephones were working. I saw two people I knew putting a wounded man on a door to take him to the hospital.

People were walking in the streets like zombies. A man we knew said to us: “My wife? My children? Where are they?”

Three-year-old Ali turned to look at me as he was being dragged by his grandmother’s hand into a rural community center turned refugee shelter. Apropos of nothing, he announced: “I was singing. I flew in the air. There was dirt everywhere. I slept in the street.”

Wilson Dumas is a taptap driver who walks with a permanent limp from a crushed tibia. He is lucky to be alive, and knows it. “I was walking down the street. The next thing I knew, I woke up and I was on the ground with my legs buried in cement. I didn’t know what had happened or how I got there. I looked to my left and my right; I was lying right between two dead people.”

I had several conversations with the soft-spoken, ever-smiling auto mechanic Gary before he ever mentioned having risked his life to save his near-dead infant. He told the story as calmly as he might have described a car repair job he’d just completed:

My house collapsed with my baby in it. She was a year and some months. Two houses collapsed in front of mine, so I had to climb across the roofs of all three houses to get there, but every time I tried to climb up the houses kept dancing, so I had to wait a couple of hours. When I got inside, my baby was lying on the bed. My godmother had fallen on top of her, and lots of blocks were on top of them, and they were both passed out. It took me a long time to move the blocks away so I could get to them. I thought my baby was dead, but when I picked her up, I could feel a little breath. She was unconscious for three or four hours, all her limbs just splayed out. Now she’s fine, and she wants to be with me every second.

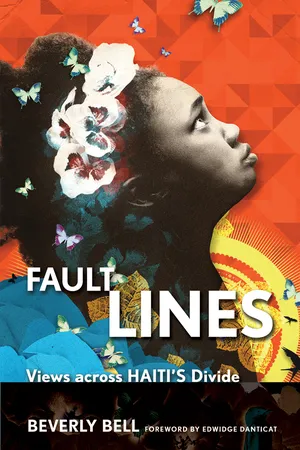

For every home destroyed, a story of life or death. Photograph by Ben Depp.

Fanfan is eleven, as thin as a blade of grass. He was standing outside his new home, this one made of a blue tarp and sticks. One wall was completely open to thousands of new neighbors who had relocated to the same park. He had lost his sandals, his only shoes, inside his house when it fell. He told his story in a voice just above a whisper:

I was trapped in the house all day long until nighttime. My house was in a three-story building, and I was on the first floor. We all started running toward the garage. Some people got out, but I didn’t. I couldn’t move because when the building collapsed, cement blocks fell on my legs. My godmother was in the room with me, and I called to her, but she was dead. I kept calling out for help, but no one heard me. Finally that night, after ten, my father pulled some blocks up and found me there. He’s a coffin-maker, and he got back from work. My mother helped him. They pulled me out.

Were you scared? “Yes.” What were you thinking about as you lay there? “I was lying there calling for someone, and I thought I might die. But I didn’t want to die, and I thought maybe God would save me.”

The old downtown around Grand Rue looked post-nuclear. The streets were ghostly and silent, and even in daytime it seemed dark. Small fires burned in the middle of roads. Nothing was intact: no infrastructure, no commerce, no community, no electricity. Here the tall buildings didn’t even pancake; they just crumbled. No vehicles moved.

Those who were out stepped slowly from high point to high point through the gray muck of the streets. Their clothes were rags, their bodies emaciated. No one smiled when I greeted them. A man sat alone on a broken chair. When I offered condolences, he shook his head and said, “It’s bitter.”

Where a bustling open-air market had recently been, several naked men pulled buckets of dark water up from a manhole. It was bathtime, post-earthquake.

Fourteen-year-old Donal appeared by my side from nowhere, wearing impossibly clean slacks and a neat polo shirt. He took it upon himself to narrate the scene. “You see these piles?” He pointed to what used to be sidewalks, where not long ago timachann, street vendors, had squatted over their wares of polka-dotted guinea hens, long- expired antibiotic pills, and dog-eared Read English without Tears paperbacks. The sidewalks had been replaced by ground concrete that looked as if it had been through a blender, and rebar bent like bread-wrapper twist ties. “All under these piles: timachann. They’re everywhere in there. The day after the earthquake you could hear people screaming all over. But no help came; people just had to dig with their fingernails.

“Then there were piles of bodies in the streets. They were stacked high, here, here, everywhere. And the smell, oh, it was terrible.”

Donal paused, then asked, “Do you think if you lost your three children you could go crazy?” Yes, you could. Do you know someone who lost three children? “Yeah. All her kids. I have another friend who came home and found every member of his family dead.”

All day, every day, I asked acquaintances and strangers their experiences of January 12. Most told about family members and others they loved who hadn’t made it. The stories of death were so profuse that a doctor told me, “They’ve become almost banal.” A Haitian friend who lives in the United States said that, by day seven, she had learned of seventy-five people close to her who had perished. After that, she stopped reading e-mail.

A taxi driver who gave me a ride until his old car gave out told me,

I lost my child. He was my only son, four years old. He and his mother were outside, and he ran into the house. She went in to get him and just then the earthquake happened. She ran back out, and he didn’t. That’s the way it is. God said there is no life without problems. When my wife cries about losing our son, I tell her: “Cheri, sweetheart, God gives and God takes away. That’s just part of what you have to expect from life.” Tears have never come from my eyes once since January 12. Life, problems. Problems, life. You have to accept it.

One afternoon a few weeks after twelve on Delmas Road, a well-groomed man pulled a red car up to the curb. The car was in ruins. Its roof, sides, doors, windshield, and windows had been sheared off as though with a jagged-edged saw. Every seat but the driver’s was mashed. And yet the vehicle was running. I walked over to look at this post-disaster innovation. “We have to take courage,” the man informed me. Did you lose your house? I asked. “My house, yes, I lost it. And my two children.” He exited the car by stepping straight out from the seat. Reaching into his wallet, he pulled out a laminated school ID of his daughter, ten-year-old Christianne Louis. In the picture, her shy smile pushed up her chubby cheeks, and her braided hair was festooned with red ribbons. “Her and my sixteen-year-old.” He said earnestly, “We’ll tell God thanks,” and sidestepped back into the car. As he maneuvered it back onto the street, he called out, “Have a nice day.” I stood stock-still and watched as he drove away.

Judith Simeon, a popular educator with women and peasant groups, told of the elderly Madame Saintilus, founder and director of a now-destroyed school. About two hundred of her students died within it. Day after day she, her sister, and her husband just sat in front of the school’s remains, under the sun and the moon, broken with grief. Judith went over and strung a sheet of plastic over their heads to protect them.

In a meeting for the survivors of a women’s micro-enterprise group, a young woman in a baseball cap said, “We’ve lost everyone. We don’t have enough water to make tears anymore.”

![]()

2

What We Have, We Share

Solidarity Undergirds Rescue and Relief

January 2010

“From the first hour, Haitians engaged in every type of solidarity imaginable—one supporting the other, one helping the other, one saving the other. If any of us is alive today, we can say that it’s thanks to this solidarity,” said Yolette Etienne. Yolette is an alternative development expert and a longtime activist who cut her political teeth in the youth rebellion against Jean-Claude Duvalier. At the time of the earthquake she was heading the national program of Oxfam Great Britain; today she does the same for Oxfam America.

Sitting in my courtyard because for many months she wouldn’t set foot in a cement building, Yolet...