Chapter 1

California in Panama

Not all the dreams kindled by the discovery of gold in January 1848 revolved around the gold itself. In Panama what mattered most was the rush that followed—the massive migration of people to the goldfields from places as disparate as Hawaii, China, France, Australia, Mexico, Chile, and Maine. In an era when ships still offered the most reliable and fastest means of travel between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States, immigrants setting off for California from the eastern seaboard found in the crossing of Panama a way to reach San Francisco that was far faster than the journey around Cape Horn. The surge in demand for transportation across the isthmus and related services offered an opportunity for Panamanians to recapture wealth on a scale that had not been seen on the isthmus since the boom years of the colonial period, when Panama had served Spain as a gateway to the Pacific coast of the Americas.

Once the gold rush began, however, no agreement followed about how to take advantage of that opportunity. At first, the gold rush seemed like a godsend to members of Panama City’s merchant elite. At the beginning of the rush, however, those who appeared to benefit most from the great demand for speedy transportation were working people of color in the transit zone. The independence displayed by workers alarmed not only members of Panama’s elite but also white immigrants from the United States, who found themselves unexpectedly dependent upon people whom many immigrants perceived as their racial inferiors. Also maddening to immigrants was what they perceived as the exploitation of their lot by steamship companies from the United States and their agents in Panama City. Rather than a straightforward conflict between nationalities, the struggle over communication in the transit route sometimes pitted people against their fellow citizens in ways that challenged conventional ideas of gender, class, citizenship, and race among Panamanians, people from the United States, and immigrants from elsewhere.

Memories of Former Times

Panama in the mid-nineteenth century was haunted by its former importance as a nodal point in Spain’s interoceanic empire. By the time the first Spanish ship appeared off the coast of Panama in 1501, native peoples, fauna, and plants had been taking advantage of the isthmus’s possibilities as a land bridge for thousands of years. Before the Spanish conquest Panama’s primary importance lay as a nexus between Central and South America. Its value as a bridge between the oceans increased dramatically, however, after the beginning of Spanish settlement in Panama in the early 1500s, and particularly after 1513, when Vasco Núñez de Balboa first glimpsed the body of water that the Spanish would come to know as the “South Sea.”

Although Panama produced modest wealth at different points during the colonial period through mining, agriculture, the slave trade, and other activities, its primary importance in the colonial economy derived from its role as a crossroads in trade routes that linked Spain to the Americas and different parts of the Americas to one another and the wider world of the Pacific. The first efforts at Spanish settlement focused on the Atlantic side of the isthmus. These initial experiments were largely abandoned after the founding of Panama City in 1519. Over the next few decades, Panama would serve as a staging ground for further Spanish conquest in Central America, Peru, and other regions of South America. By the middle of the 1500s, Panama had emerged as an important hub in the Spanish fleet system—a shipping network that connected officially designated ports in the Americas on a regular basis to Spain. In this capacity, Panama became the primary conduit for mineral wealth from the Pacific coast of South America to Spain and the principal point of entry for European goods and enslaved Africans heading in the opposite direction. Two basic strategies were used to connect the two coasts of the isthmus during the colonial period. One involved the transport of people and cargo by mule across the isthmus on roads. The other combined mule transport with transport by boat up and down the Chagres River, which flowed from the interior of the isthmus to its mouth at the port of Chagres, located on the Atlantic coast. A network of roads connected Panama City to the Atlantic coast and to the principal inland ports on the Chagres, Cruces and Gorgona. On Panama’s Atlantic coast the port of Nombre de Díos and later the port of Portobelo became the site of trade fairs that gained fame throughout the Atlantic world.

Geography in and of itself was no guarantee of Panama’s importance as a place of transit. The flow of people and goods across the isthmus varied with changes in Spanish trading and navigation policy, attacks by Spain’s enemies, and the productivity of different areas of the Spanish colonial economy. During the early colonial period, communication across the isthmus was sometimes harried by indigenous peoples as well as maroons—Africans who had escaped slavery and established palenques, or independent settlements, in the neighborhood of the transit zone. What began as one of Panama’s advantages, its proximity to Spain’s political and commercial centers in the Caribbean, became a source of vulnerability as Spain’s European enemies extended their reach into the region. Panama became an important site for contraband trade between merchants in Panama and Spain’s imperial rivals. Panama’s transit route attracted the attention of pirates. The most devastating attack came in 1671, when Henry Morgan, the Welsh buccaneer, carried out a raid that resulted in the destruction of Panama City. Another threat from abroad arose at the turn of the eighteenth century, when a small group of Scots led by William Paterson attempted to start a colony on Panama’s Caribbean coast, in the region known as Darién. While the Scots managed to form alliances with indigenous people in the region, the colonization effort soon collapsed under pressures that included disease, internal organizational problems, and Spanish harassment. In 1739 an English attack on Portobelo led by Edward Vernon contributed to a shift in Spanish navigation policy that channeled traffic between Spain and the Pacific coast of South America by way of Cape Horn rather than Panama. The history of the transit route through the rest of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was one of decline marked only occasionally by modest, short-term increases in traffic.

Independence and Union with Gran Colombia

The Spanish American wars of independence in the 1810s briefly revived Panama’s importance as a transit point, as the Spanish sought an alternative to the interoceanic route across war-torn Mexico. Panama itself saw little combat during this period other than a failed attack on Portobelo in 1819 by Gregor MacGregor, a Scot in the service of South American patriots. This period of relative prosperity came largely to an end, however, with Spanish defeats in South America. Members of Panama’s elite of merchants and landowners declared the independence of the isthmus once the likely fate of the Spanish empire on the American mainland had become clear. Independence was declared first in the provincial town of Villa de los Santos and then in Panama City. Rebels used bribes to convince many of the Spanish troops in Panama City to desert, and no blood was shed for the cause of independence in the capital city of the isthmus. The declaration of independence signed in Panama City on November 21, 1821, announced the adherence of Panama to Simón Bolívar’s newly created Republic of Colombia, or Gran Colombia, as historians have come to call it, which included not only the modern-day nation of Colombia but also Venezuela and Ecuador. Panama was now to be ruled not from Spain but from Bogotá.

Although Simón Bolívar never set foot in Panama himself, he gave the isthmus a prominent place in the new political geography he imagined for the Americas. In his “Letter from Jamaica” of 1815, he expressed his hope that the Isthmus of Panama might someday become “the emporium of the world” and even the future site of the world’s capital. He invested the isthmus with further significance when he chose Panama City as the site of the Congress of Panama, an attempt in 1826 to craft an international alliance capable of protecting the independence of the states carved out of Spain’s mainland empire. Although the congress proved to be a disappointment, Bolívar’s identification of Panama as a symbolic bridge among nations would exercise a powerful influence on advocates of political unity among Spanish-speaking polities in the hemisphere, and on Panamanians in particular.

Despite Bolívar’s hopes for the isthmus, independence from Spain and rule from Bogotá failed to rescue Panama from penury. Although the government of Nueva Granada granted a number of privileges to foreign contractors after 1821, no major improvement was made in the infrastructure of the route in the two decades leading up to the discovery of gold in 1848. Even if a contractor had begun serious work, Panamanian merchants would have had to confront a deeper problem: the more general drop in trade between Europe and the Pacific coast of the Americas caused by the wars of independence. The bulk of what little trade took place between Panama and other parts of the world in the decades after independence was with the British island of Jamaica.

Although international commerce in Panama was stimulated by the expansion of British steamship service to both sides of the isthmus in 1842, traffic across the interoceanic route between 1821 and 1848 remained miniscule compared with the boom times of the colonial period. Frustration over this decline fed political discontent in Panama City and contributed to short-lived independence movements against Bogotá in 1826, 1830, 1831, and 1840–41. In 1830 Gran Colombia itself splintered into three independent republics: Ecuador, Venezuela, and Nueva Granada. In this new configuration of political power, Panama remained part of Nueva Granada.

Elite politics in Panama City in the early nineteenth century were driven by the goal of reestablishing the commercial and political importance Panama had enjoyed during its years of prosperity in the colonial period. The name that members of Panama City’s mercantile elite gave to the ideal they sought was the same word Bolívar had used in his “Letter from Jamaica”: “emporium.” This vision of an emporium included both economic and political dimensions. Realizing that Panama lacked the technology and the capital to make major improvements in the route itself, boosters of the transit economy sought to revive the physical infrastructure of the route with the help of foreigners capable of building a canal or a railroad or at least repairing the roads leading across the isthmus, which had eroded seriously by the early nineteenth century. Elite political leaders also expressed support for Panamanian autonomy or outright independence from Bogotá, free trade, and the related concept of “neutrality,” or the idea that the transit route should be open to all nations.

None of the revolts against Bogotá in the early nineteenth century involved large-scale military mobilization, and in each case Panama was reintegrated into the national polity with little or no bloodshed. The most sustained effort at separation began in 1840 and ended one year later, when the Panamanian leaders of the rebellion rejoined Nueva Granada voluntarily. Members of Panama City’s elite formed the basis of support for these abortive independence movements. The only revolt with significant popular participation was led in 1830 by Gen. José Domingo Espinar, a man of color from Panama City who had studied medicine and engineering in Peru and distinguished himself as an officer and a close ally of Bolívar during the wars of independence.

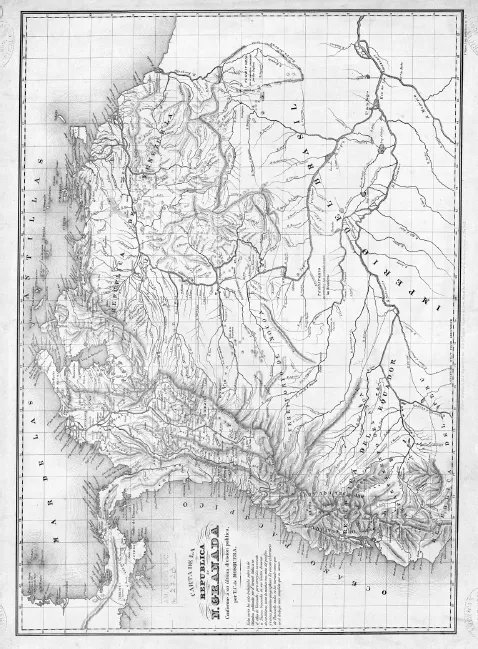

Fig. 1. Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera.“Carta de la República de N. Granada por T.C. de Mosquera.” 1852. Courtesy of American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The Population of the Isthmus

Sparse census data make it difficult to be precise about the people who inhabited the Isthmus of Panama on the eve of the gold rush. In contrast to censuses taken in the United States in the same period, official records in Nueva Granada did not tabulate the race or color of the country’s inhabitants, and the government of Nueva Granada controlled only portions of the isthmus. The official census of 1851 indicated that the entire population of Panama (excluding indigenous peoples) was 138,108. Of those, 52,322 resided in the province of Panama itself, which included Panama City and the transit route.

The basic contours of Panama’s social geography in the mid-nineteenth century were shaped early in the colonial period. The transit zone was the most densely populated region of the isthmus and also the place where the power of the provincial government was strongest. The zone was inhabited almost exclusively by individuals of African or Spanish descent and people of mixed origins. The term “negros” or “blacks” became politically charged in Panama and elsewhere in Nueva Granada after independence because of its identification with slavery, an institution that revolutionary governments had officially repudiated. In Panama, “gente de color” or “people of color” was a less controversial term in republican discourse, one that embraced all people who were perceived to descend at least partially from Africans, including people of mixed European and African descent, or mulatos. Although less common in Panama by the mid-1800s, the term “pardo” was also used to describe free blacks and mulattos in Panama and elsewhere in Nueva Granada. In contrast to Mexico and some other parts of the Spanish-speaking Americas, the term “mestizo” was rarely used in Panama in the mid-1800s to describe people of mixed indigenous and European descent. Instead, the term “castas” (castes) was used to describe people of mixed descent more generally, including gente de color.

Gente de color formed the majority of the transit zone’s population. The regions located to the east of the transit zone, where the provincial government of Panama maintained a minimal presence, were populated mainly by people of African origins descended from maroons who had escaped from slavery during the colonial period and indigenous peoples. Indigenous people and gente de color also predominated in the region along the Atlantic located to the west of the transit zone, where the provincial government was also nearly nonexistent. The presence of governing institutions controlled by Spanish-speaking people was far stronger along the Pacific coast west of Panama City, ...