- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition

About this book

Why did the Peace of Nicias fail to reconcile Athens and Sparta? In the third volume of his landmark four-volume history of the Peloponnesian War, Donald Kagan examines the years between the signing of the peace treaty and the destruction of the Athenian expedition to Sicily in 413 B.C. The principal figure in the narrative is the Athenian politician and general Nicias, whose policies shaped the treaty and whose military strategies played a major role in the attack against Sicily.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition by Donald Kagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Unraveling of the Peace

In March of 421, after ten years of devastating, disruptive, and burdensome war, the Athenians and the Spartans made peace on behalf of themselves and those of their allies for whom they could speak. Weariness, the desire for peace, the desire of the Athenians to restore their financial resources, the Spartans’ wish to recover their men taken prisoner at Sphacteria in 425 and to restore order and security to the Peloponnesus, the removal by death in battle of the leading advocate of war in each city—all helped to produce a treaty that most Greeks hoped would bring a true end to the great war. In fact, the peace lasted no more than eight years, for in the spring of 413, Agis, son of Archidamus, led a Peloponnesian army into Attica, ravaged the land as his father had done eighteen years earlier, and took the further step of establishing a permanent fort at Decelea.1

Ever since antiquity the peace has borne the name of Nicias,2 the man who more than any other brought it into being, defended it, and worked to maintain it. Although the years 421–413 easily fall into two phases, before and after the Athenians launched their invasion of Sicily, the entire period is given unity by the central role played in it by Nicias. Relations between Greek states and between Athenian factions were volatile in these years, but Athens remained the vital and active power in the Greek system of states, and Nicias was the central figure in Athens. Stodgier, less spoken of, and less impressive than his brilliant contemporary Alcibiades, he nonetheless was more responsible than anyone else for the course of events. The death of Cleon had left Nicias without a political opponent who could match his own experience and stature. The Athenian defeats at Megara and Delium and the loss of Amphipolis and other northern cities made Nicias’ repeated arguments for restraint and a negotiated peace with Sparta seem wise in retrospect. His chain of successful campaigns unblemished by defeat and his reputation for extraordinary piety further strengthened his appeal to the Athenian voters. At no time since the death of Pericles had an Athenian politician had a comparable opportunity to achieve a position of leadership and to place his own stamp on the policy of Athens. As it is natural to connect the outcome of the Archidamian War with the plans and conduct of Pericles, so it is appropriate and illuminating to see how the outcome of the Peace of Nicias, in both its phases, was, to a great extent, the product of the plans and conduct of the man most responsible for creating it and seeking to make it effective.

1 7.19.1–2. All references are to Thucydides unless otherwise indicated. The precise duration of the formal peace is much debated, for Thucydides’ remark in 5.25.3 that Athens and Sparta held off from invading each other’s territory ϰαὶ ἐπὶ ἕξ ἔτη μὲν ϰαὶ δέϰα μῆνας ἀπέσΧοντο μὴ ἐπὶ τὴν ἑϰατέϱων γῆν ατϱατεῦσαι, cannot be squared with his account of the Athenian attack on Laconia in the summer of 414. Since Thucydides himself emphasizes that fighting continued throughout the entire period, the point is not of great importance. Modern scholars treat the entire period from the peace of 421 to the destruction of the Sicilian expedition as a unit. For a good discussion of the chronological problems see HCT IV, 6–9.

2 Andoc. 3.8; Plut. Nic. 9.7, A/c. 14.2.

1. A Troubled Peace

No amount of relief and rejoicing by the Spartan and Athenian signers of the Peace of Nicias could conceal its deficiencies. The very ratification of the peace revealed its tenuous and unsatisfactory character, for the Boeotians, Eleans, and Megarians rejected the treaty and refused to swear the oaths.1 Nor did Sparta’s recently acquired allies in Amphipolis and the rest of the Thraceward region accept the peace, which required them once again to submit to the unwelcome rule of Athens.2 The Spartans and Athenians drew lots to see who should take the first step in carrying out the treaty, and the Spartans lost. An ancient story says that Nicias used his great personal wealth to assure the outcome, but if the story is true he wasted his money.3 The Spartans, to be sure, returned such Athenian prisoners as they held and sent an embassy to Clearidas, their governor in Amphipolis, ordering him to surrender Amphipolis and force the other cities of the neighborhood to accept the peace treaty (see Map 1). Sparta’s allies in Thrace refused the demand and, even worse, Clearidas did the same. In defense of his refusal, Clearidas pointed to the Amphipolitans’ unwillingness to yield and his own inability to force them, but, in fact, he himself was unsympathetic to the order and unwilling to carry it out.4 He hurried back to Sparta to defend himself against possible charges of disobedience and to see if the terms of the treaty could be changed. Although he learned that the peace was already binding, Clearidas returned to Amphipolis with slightly but significantly modified orders: he was to “restore Amphipolis, if possible, but if not, to withdraw whatever Peloponnesians were in it.”5

These orders were a clear breach of both the spirit and the letter of the peace. The treaty required the Spartans to restore the city to Athens, not to abandon it to the enemies of Athens. The restoration of Amphipolis was Athens’ foremost material aim in making peace, and the Spartans not only failed to deliver it but tacitly condoned their governor’s conspiracy to keep it out of Athenian hands. Sparta’s first action was not likely to inspire trust among the Athenians.6

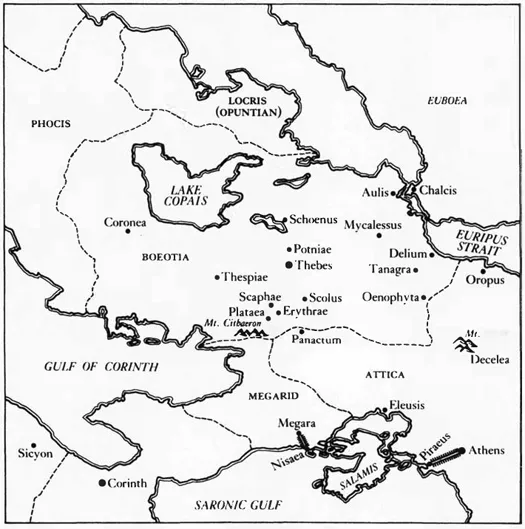

The continued resistance of Sparta’s nearer allies further threatened the chances for continued peace. Clearidas’ visit to Sparta must have come at least two weeks after the signing of the Peace of Nicias, but the allied delegates were still there.7 The Spartans must have spent the intervening time trying to persuade them to accept the treaty, but with no success. Each ally had good reasons for rejecting the peace. Megara had suffered repeated ravages of her farmland and an attack on the city that almost put it into Athenian hands. Worse yet, its main port on the Saronic Gulf, Nisaea, had fallen under Athenian control and the peace did not restore it. This loss threatened both the economy and security of Megara (see Map 2). Elis rejected the peace because of a private quarrel with Sparta.8

The Boeotians’ refusal to accept the peace is harder to explain. Thucydides’ narrative reveals that they refused to restore to the Athenians either the border fortress of Panactum, which they had seized in 422, or the Athenian prisoners taken in the Archidamian War. But these were not reasons for the Boeotian unwillingness to accept the peace, merely evidences of it. Though Thucydides explains the motives of the other recalcitrant allies of Sparta he does not do so for the Boeotians, so we can only speculate. The Boeotians, led by the Thebans, seem to have acted out of fear. Theban power, prestige, and ambition had grown greatly during the war. In 431, or soon thereafter, the citizens of Erythrae, Scaphae, Scolus, Aulis, Schoenus, Potniae, and many other small unwalled towns had migrated to Thebes and settled down, doubling the size of the city9 (see Map 2). In 427 the Spartans gained control of Plataea and turned it over to their Theban allies. Within a short time the Thebans destroyed the city and occupied its territory.10 Probably then, or soon after, the number of Thebes’ votes in the Boeotian federal council was increased from two to four; “two for their own city and two on behalf of Plataea, Scolus, Erythrae, Scaphae,” and a number of other small towns.11

Map 1. The Chalcidice

Map 2. Attica and Boeotia

The power and influence of the Thebans had been further increased by the leading part they played in the victory over the Athenians at Delium.12 They took advantage of this new power in the summer of 423 when they destroyed the walls of Thespiae on the grounds that the Thespians sympathized with Athens. “They [the Thebans] had always wanted to do this, but it was now easier to accomplish since the flower of the Thespians had been destroyed in the battle against the Athenians [at Delium].”13 Since these gains had occurred while Athens was distracted by a major war against the Peloponnesians, the Peace of Nicias was a threat to the new Theban position. The end of Sparta’s treaty with Argos, and the discontent and disaffection of Corinth, Elis, and Mantinea guaranteed that the Spartans would be fully occupied in the Peloponnesus. They could not, even if they would, prevent the Athenians, newly freed from other concerns, from interfering in Boeotia. The democratic and separatist forces in the Boeotian cities would surely seek help from the Athenians, who might be glad to assist them in hopes of restoring the control over Boeotia which they had exercised between the battles of Oenophyta and Coronea. So frightened were the Thebans that, even while rejecting the Peace of Nicias, they negotiated an unusual, if not unique, truce with the Athenians whereby the original cessation of hostilities was for ten days; after that, termination by either side would require ten days’ notice.14 Such fears, along with great ambitions, made the Thebans hope for the renewal of a war that would lead to the defeat of Athens and the destruction of its power.15

Of all Sparta’s allies Corinth was least satisfied with the peace. None of the grievances that had led the Corinthians to push the Spartans toward war in 431 had been removed. Potidaea was firmly in Athenian hands, its citizens, descendants of...

Table of contents

- Abbreviations and Short Titles

- Part One. The Unraveling of the Peace

- Part Two. The Sicilian Expedition

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Modern Authors

- Index of Ancient Authors and Inscriptions