![]()

1 RESISTANCE IN SURVIVAL

The bamboo symbolizes the Haitian people to a T, eh? We are a little people. The bamboo is not a great big tree with a magnificent appearance. But when the strong winds come, well, even a great tree can be uprooted. The bamboo is really weak, but when the winds come, it bends but it doesn’t break. Bamboo takes whatever adversity comes along, but afterwards it straightens itself back up. That’s what resistance is for us Haitians: we might get bent…by globalization, but we’re able to straighten up and stand.

—Yolette Etienne

By resistance I mean the ingenuity we use that allows us to live. Resistance is inside how we do the thing that lets us hold on and gives us a better way. It’s in the very manner in which we organize ourselves to survive our situation.

—Vita Telcy

INSISTING ON LIFE

Marlene Larose is a woman with an indomitable spirit and a ferocious will. She has a dozen pseudonyms, Marlene Larose being one, and underground affiliations. Her large body and deep voice assert themselves in any situation; her dark eyes bore with disconcerting intensity. You would not want this woman as your enemy.

The death squads didn’t either, and they threatened to kill her. Undaunted, she moved her husband and four children out of their home and onto a rooftop. Taking advantage of the visibility afforded by their open-air residence, they took up surveying and documenting the death squads’ activities, even sending for infrared film from human rights organizations in the United States, to photograph the killers on their nightly rounds.

Marlene’s commitment to democracy has not come cheaply. Her eighty-three-year-old mother was assassinated and dismembered in 1983. In 1988, Marlene was shot twice—once in her neck and once between her lung and heart—when zenglendo stormed a mass she was attending.

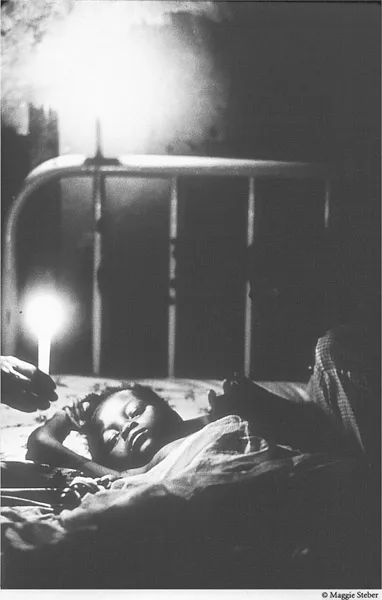

Several years later, Marlene became pregnant. Doctors discovered that the bullet that had lodged near her heart had traveled down to her womb. They warned that her fetus and her own health were threatened. Marlene refused to abort her baby.

Her story echoes the themes of this book—survival, resistance, and occasional triumph by women with little formal power. It highlights Marlene’s own resilience against the forces encroaching on her claim to life. Like all the istwa in this book, Marlene’s story reveals how so-called private decisions and behavior can become willful acts against dehumanization or destruction.1

Despite the medical risks, Marlene survived. And somehow, sharing the womb with a bullet, her fetus did as well. Finally Tibi entered the world, healthy, pudgy, and cherubic. “They tried to kill that baby” Marlene said, “but he insisted on becoming life.”

DAILY ACTS OF RESISTANCE

Popular snacks in Haiti are peze souse, squeeze and suck, frozen pops in plastic bags that are consumed by people sucking from the top while squeezing from the bottom. The istwa in this chapter are told by women being consumed like a peze souse.2

The griyo describe the pernicious effects of structural violence, what Paul Farmer et al. defined as “a series of large-scale forces—ranging from gender inequality to racism to poverty—which structure unequal access to goods and services.”3 This structural violence is felt in their daily lives, for example, from small farmers’ inability to feed their families due to U.S.- and World Bank-imposed free market policies that have destroyed their subsistence production, to the large landowners’ control of irrigation systems. It is felt in the lack of medical care for their infants because the government budget includes almost no social spending.

As prevalent in the istwa are women’s deployment of their internal resources to leverage small advantages in the daily battles against structural violence. When they cannot increase their power, still they try to keep the margins of power from shifting further to the individuals, political institutions, and economic systems that oppress them. It sometimes takes all their energy just to hold on to what they have, materially and spiritually.

In so doing, the women expand the definitions of political action and resistance. They demonstrate what American religious scholar Howard Thurman called “the creative capability of personality to grow in the midst of no-growth circumstances; to find faith in the midst of fear, healing in the midst of suffering, love in the midst of hate, hope in the midst of despair, life in the midst of death, and community in the midst of chaos.”4

The women’s negotiations with dominant power usually go unseen. The boundaries of those negotiations are often small and may be viewed as personal. The women do not necessarily articulate the theories behind their actions, or the connection to larger social movements. Yet the deliberateness of their acts indicates clear refusal to cede ideological or personal space to their oppressors.

Detecting the prevalence of dissent among Haitian women necessitates radically changing one’s perceptions of what resistance is and where to look for it. It requires asking, What are the forces that these women overcome each day to sustain themselves and their families? What negotiation is involved in their maintaining their humanity? And what sort of “personal” or “private” actions may, with a widened gaze, be revealed to be as political as a union strike?

Not all women are protesting or even fighting defeat. Some may have given up, for the time being or permanently. Still, what might look to be a completely beaten-down victim might be something quite different, as Roselie Jean-Juste, survivor of domestic abuse, illustrates. Her hand crippled by a beating from her husband, her face and carriage showing the strain of life on the run from him, at first glance Roselie seems broken. On the contrary. When she came to our meeting to give her narrative, Roselie had just left a human rights advocate from whom she was seeking help. She also was engaged in complex self-protection strategies, including sleeping at a different house each night. And she was vehement about having her full story, including her husband’s name, told in this book so as to publicize the man’s brutality and pressure him to stop.

MAINTAINING LIFE

There is a Haitian saying…. Nou lèd, Nou la. We are ugly, but we are here. For most of us, what is worth celebrating is the fact that we are here, that we against all the odds exist. To the women who might greet each other with this saying when they meet along the countryside, the very essence of life lies in survival. It is always worth reminding our sisters that we have lived yet another day to answer the roll call of an often painful and very difficult life.

—Edwidge Danticat

Given Haiti’s extreme circumstances, mere survival can be an implicit protest against attempted extermination. Often only sheer will, coupled with tremendous creativity and resourcefulness, allows the maintenance of body and spirit.

Maria Miradieu’s resistance is in her renewed efforts to defy starvation of her children and to assert her human value each day. Every morning this woman rises at four o’clock to prepare a meager pot of rice for her four children before heading for the crowded, noisy market to garner a few santim, pennies, from selling mangoes. Her protest includes fighting off physical exhaustion aggravated by the weakness of hunger. As she has no money for the bus, it requires mustering the strength to walk miles to the market, enduring fast and careless cars, the stench of open sewers, and dust and filth. On the job, she publicly ridicules anyone trying to barter down her already-low price so that she can maintain her dignity and preserve the tiny margin of profit she desperately needs.

In Haiti, more than one in ten children do not make it to the age of five. Of those who do, the average life expectancy is just over fifty-three years.5 But these figures recount only a small part of the story; the full wretchedness of the poverty cannot be conveyed in tidy numbers. So how is it that Haitian women continue to cope and persist?

The istwa in this chapter reveal many strategies. Ingenuity, for example, is a form of resistance when survival means creating something out of nothing. Yolande Mevs recalls returning home empty-handed from a long day of wandering the streets, seeking food for her worm-bellied kids:

I told them, “Little ones, today I ran my head into walls everywhere…. Everything that could have saved me, didn’t.” I took a pot I had, I put a little salt in the pot. I made salt water. Only my first child didn’t drink it. All the other children drank the salt water and then they went to sleep.

In Haiti, this type of effort is called sou fòs kouray, on the strength of your courage.

Vita Telcy describes her efforts to meet her strategic needs and interests this way:

Rich people eat three times a day, me I can’t. When I harvest five cans of corn, today my family can eat half a pound. Tomorrow if there’s a cup, I’ll cook it. I maximize those five cans like so: one can to send the children to school, one can to send a sick child to the hospital, one can for all the family to eat. With what’s left over, I find seeds to plant to make sure I can grow next year. This is how I see resistance with an economic face.

What happens at the level of domestic partnership, also, is central to women’s resistance strategies. In one of many examples, as in Celine Edgar’s story in the introduction, women speak of consenting to relationships in the hope that a man will provide additional economic support for the household.

DEFYING DEGRADATION

I learned to be vigilant in the nourishment of my spirit, to be tough, to courageously protect that spirit from forces that would break it.

—bell hooks

A market woman bends down and raises the pink plastic bucket of tomatoes and onions to her head. All the while she sings.

“Your heart is happy this morning, Madanm," I say.

She surveys me. “It’s not happy, no.”

“But I see you’re singing.”

‘I’m making an effort. I’m trying to kanpe djanm, stand strong”

Using the resources available to her, this woman’s song is one of countless acts of defiance that Haitian women wage each day to sustain pride, dignity, and hope.

The story of Lovly Josaphat is another example of holding strong. Lovly is raising six children alone, after a first husband was murdered by a death squad, and a second fled after raping her oldest child. Lovly lives in Cité Soleil, the poorest and most densely populated 2.5 square kilometers in this hemisphere, where the family slogs through sewage to reach its stifling one-room home. Lovly’s survival requires overlooking or accommodating problems as best she can, this in turn demanding resilience and psychological fortitude. For example, after detailing the pervasive violence found in Cité Soleil, Lovly says, “But I like my neighborhood. It’s quiet there.” This attitude does not signify acceptance—she denounces the conditions elsewhere in her istwa; it is her attempt to change the effect of the problem when she cannot change the source.

HOPE

This hope of the poor is an elusive, underestimated, yet determinant stratum of resistance. The “secret weapon”…is insurgent hope that, like a phoenix, rises from the ashes of charred villages, pulses in hands that have been shackled and hearts that have been broken.

—Renny Golden

Her rangy body is too large for the milk crate on which she is sitting. Yolande Mevs scratches her left calf with her right foot. A survivor of coup violence from the slum of Martissant, she says, “We know that we can’t live without hope.” That hope is heard often in the phrase fòk sa chanje, this must change. It is inconceivable that life will forever remain this desperate.

What keeps hope alive in Haiti? From a Western cause-and-effect analysis, it should have fled the country long ago. And yet, as Haitians often remind each other in rough moments, they cling to their stubborn belief in change because they don’t have the luxury of despair. Nun and agronomist Kesta Occident says:

We Haitians give ourselves reasons to live, reasons to believe that one day our lives will change, even if not for ourselves, then for the generations after us. If they kill a woman with misery and hunger, she’ll die with the hope that her kids will live better.

A common Creole proverb is Kote genlespwa, genlavi. Where there is hope there is life. Hope for yon alemyè, a better go of it, yon pi bon demen, a better tomorrow. When asked how they maintain their hope in the face of such suffering, poor Haitians readily offer up their reason: Nou pagen lechwa. We don’thave a choice. In fact, they do have a choice. Despair, crack cocaine, grain alcohol, and suicide are also available to them. While some Haitians do go down these roads, many more get by in dire times through the crucial resource of positive expectation.

Squatting over a blackened pot and poking at the burning charcoal under it, Lovly Josaphat says,

When I was a child…life was easier. I would buy sugarcane, ...